Lesson Plans

Course Links

Lesson Plans

Course Documents Links

Secondary Sources

Quick Links

Library Links

Citing

Sources

The Adventures of

Huckleberry Finn

Samuel Clemens/Mark Twain

1885

Terms | Life | Times | Class Discussion | Group Questions | Links | Pictures | Quotes from Critics

http://tinafloystad.files.wordpress.com/2008/01/mark-twain.jpg

Terms to Know

For your note card: slavery, lying, con-men,

river, violence, peace, money, religion, conscience, morality,

social values, domesticity,

Link to the illustrated novel

You think Huck Finn is hard to read . . . . Check out George Harris' Sut Lovingood

OED words: "quality"

Arcadia: A literal place -- a remote region in the Greek Islands encircled by mountains -- but more importantly, a potent literary symbol from the Latin times (cf. Virgil's Eclogues) on through today (cf. Tom Stoppard's play of the same name). It's a deliberate look back to a mythic Golden Age, when all was right with the world, and shepherds roamed in a pastoral idyl. The physical place contributes to its symbolic meaning: a place (and thus ideal) cut off from "real" world. Once the real world intrudes (a visitor from another region), the gold tarnishes, and things fall apart. Stemming from human's perennial desire for a mythic (longed for but never really existing) perfect time, its obvious analogue is the Garden of Eden Myth. Wolfgang Iser brings up an important point about Arcadia: “Should the world intrude upon its borders, then thanks to the total self-containment of the garden, it is the world that will seem excluded and unreal” (73).

Iser, Wolfgang. Prospecting:

from Reader Response to Literary Anthropology.

Baltimore: John Hopkins UP, 1989. Print.

Southwestern humor: Characterized by tall

tales, exaggeration, dialect, and exotic (for those living on the

Eastern seaboard) locales, this genre presented the frontier (in

the mid 1800s, "the West" started at Missouri -- and for some,

Ohio) in a, well, humorous light. "Well-known noms de guerre

such as 'Artemus Ward' (Charles Farrar Browne), 'Petroleum

V. Nasby' (David Ross Locke), and 'Josh Billings' (Henry Wheeler

Shaw) preceded [Twain]. These comic writers, all forgotten now,

formed a school of seemingly illiterate backwoodsmen whose common

sense exposed the stupidities of contemporary American life; and

also, in the Huckleberry Finn manner, each spoke in his natural

idiom." (Hearn cliii)

Picaro/picaresque narrative: A picaro is a lower class figure living on his wits -- and whose actions border on the criminal. Often used to offer wry comments/critiques on society. A picaresque narrative follows such a hero/rouge through various and often seemingly random escapades. According to Harmon and Holman's A Handbook to Literature, a picaresque novel includes: 1) biography (whole or part) of a picaro -- first person POV; 2) episodic; 3) picaro does not grow or develop as a person; 4) realistic in presentation (though at times fantastic in action) and (usually) satiric in aim.

Burlesque : A work designed to ridicule a style, literary form, or subject matter either by treating the exalted in a trivial way or by discussing the trivial in exalted terms (that is, with mock dignity). Burlesque concentrates on derisive imitation, usually in exaggerated terms. Literary genres (like the tragic drama) can be burlesqued, as can styles of sculpture, philosophical movements, schools of art, and so forth. See Parody, Travesty .*

Minstrel show/Blackface: A common form of entertainment in Victorian America, this featured actors in blackface (white men with painted faces and wigs to resemble Negroes) speaking in broad Negro dialects, performing skits (usually with music and dancing) that accentuated and perpetuated stereotypes of the innocent/dumb/gullible "darky." It cast a bright picture on a dark historic past, turning slavery into comedic sketch. Twain loved minstrel shows.

See "Minstrel Show" in The Oxford Companion to American Literature for a brief overview, and an excellent wikipedia page (great period illustrations) for a more detailed explanation.

Jim Crow: Literally, stock character from minstrel shows (see above). More generally, a stereotypical figure originally used as a caricature of a black male. In the years following Reconstruction, laws were passed throughout the United States legalizing segregation and denying rights to blacks. These laws were called Jim Crow laws.

Realism: A literary movement that focuses on the matter of fact, the every day life, and attempts to report it objectively. While purporting to ignore morality, simply illustrating reality has a way of instigating changes.

Two criticisms of realism include 1) it generally focused on middle to upper class life and thus didn't represent "real life." And 2) any attempt at objectivity is doomed because an artist will always be limited by their subjectivity.

For additional information, see the "Realism" paragraph entry in the Oxford Companion to American Literature. For a richer discussion, see the Naturalism and Realism essay from The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature.

Irony : A mode of expression, through words (verbal irony) or events (irony of situation), conveying a reality different from and usually opposite to appearance or expectation. A writer may say the opposite of what he means, create a reversal between expectation and its fulfillment, or give the audience knowledge that a character lacks, making the character's words have meaning to the audience not perceived by the character. In verbal irony, the writer's meaning or even his attitude may be different from what he says: "Why, no one would dare argue that there could be anything more important in choosing a college than its proximity to the beach." An example of situational irony would occur if a professional pickpocket had his own pocket picked just as he was in the act of picking someone else's pocket. The irony is generated by the surprise recognition by the audience of a reality in contrast with expectation or appearance, while another audience, victim, or character puts confidence in the appearance as reality (in this case, the pickpocket doesn't expect his own pocket to be picked). The surprise recognition by the audience often produces a comic effect, making irony often funny.

To be an effective piece of sustained irony, there must be some sort of audience tip-off, through style, tone, use of clear exaggeration, or other device.*

Manichean: A belief that life consists of a war between good and evil and thus always involves strife and struggle -- or sturm und drang.

Satire : A literary mode based on criticism of people and society through ridicule. The satirist aims to reduce the practices attacked by laughing scornfully at them--and being witty enough to allow the reader to laugh, also. Ridicule, irony, exaggeration, and several other techniques are almost always present. The satirist may insert serious statements of value or desired behavior, but most often he relies on an implicit moral code, understood by his audience and paid lip service by them. The satirist's goal is to point out the hypocrisy of his target in the hope that either the target or the audience will return to a real following of the code. Thus, satire is inescapably moral even when no explicit values are promoted in the work, for the satirist works within the framework of a widely spread value system. Many of the techniques of satire are devices of comparison, to show the similarity or contrast between two things. A list of incongruous items, an oxymoron, metaphors, and so forth are examples. See "The Purpose and Method of Satire" for more information.*

Trickster: "World mythology tales that involve a

rule-breaking character type. As folklore dictates social

behaviors, the trickster identifies boundaries by crashing through

them. The archetypal fool, surprised by objects before him,

sometimes powerless, the trickster also embodies the magician,

whose mastery over the natural world initiates innovation. He is

the mutant gene propelling evolution, the fire bringer, the Old

Testament serpent elevating mankind from animal existence to

divine knowledge of good or evil. Western culture frequently looks

at indigenous tricksters and sees the devil, but the trickster is

amoral, not immoral, and certainly not evil. The trickster

indicates change and new ways of behaving" (Friedman).

Romanticism/Romance novel: For Twain, novels that

revel in hair-breadth escapes, damsels in distress, sword fights,

noble men fighting ignoble villains, pirates, highwaymen,

cannibals, (oh my!). In other words, escapist fiction: and

unfortunately, Tom Sawyer's daily bread.

For Twain, the nadir of the romance novel is embodied in Sir Walter Scott, a (very) popular writer of historical fiction. In Life on the Mississippi (1883), which he wrote after completing half of HF, Twain argued (with tongue only partly in cheek) that Scott, "with his enchantments [ . . . checked the] wave of progress, and even turns it back; sets the world in love with dreams and phantoms; with decayed and swinish forms of religion; with decayed and degraded systems of government; with the sillinesses and emptinesses, sham grandeurs, sham gauds, and sham chivalries of a brainless and worthless long-vanished society. He did measureless harm; more real and lasting harm, perhaps, than any other individual that ever wrote. Most of the world has now outlived good part of these harms, though by no means all of them; but in our South they flourish pretty forcefully still. Not so forcefully as half a generation ago, perhaps, but still forcefully."

Sentimentality: This kind of literature exults in scenes depicting strong emotions, such as deathbed vignettes (particularly with children), children being abused or separated from their parents, and scenes of characters overcome with emotions and/or crying. These are meant to evoke a curious mix of pain and pleasure. Consider the following definition of sadness after the death of a loved one from a popular 1854 gift-book. After describing the initial realization of sadness as "gloomy and solemn as the death-knell," it offers an interesting qualification: "Still it is a delicious sort of sorrow; and like a cloud dimming the sunshine of the river, although causing a momentary shade of gloom, it enhances the beauty of returning brightness" ( Scrap-Book 353). Pathos, in this case a remembrance of things past, has the power to conjure up both darkness and light. Which character in HF seems locked in a sentimental waltz?

For a more detailed look at this literary genre, see this essay on sentimental literature in the Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature.

Friedman, Monica. "Trickster Tales." The Oxford Encyclopedia of Children's Literature. Edited by Jack Zipes. Oxford University Press 2006. Oxford Reference Center. Ocean County College. 3 February 2009.

*from Robert Harris's http://www.virtualsalt.com/litterms.htm

The Life

Essay

on the culture and time period of the novel

Mark Twain: "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn," in Literature

and Its Times: Profiles of 300 Notable Literary Works and the

Historical Events that Influenced Them, Volume 2: Civil Wars to

Frontier Societies (1800-1880s), edited by Joyce Moss and

George Wilson, Gale Research, 1997. Reproduced in Literature

Resource Center.

See the introduction to the Twain section for a succinct biography. On censorship of the novel, consider the following:

Susy Clemens wrote "Ever since papa and mama were married papa has written his books . . . and she has expurgated them. Papa read Huckleberry Finn to us in manuscript . . . and then he would leave parts of it for mama to expurgate, while he went off to the study to work, and sometimes Clara and I would be sitting, with mama while she was looking the manuscript over, and I remember so well . . . one part particularly which was perfectly fascinating it was so terrible, that Clara and I used to delight in and oh, with what despair we saw mama turn down the leaf on which it was written, we thought the book would be almost ruined without it. Be we generally come to think as mama did" (Hearn xxvi)

Twain noted in 1906 "I often abused my editor's innocent confidence. I often interlarded remarks of a studied and felicitously atrocious character purposely to achieve the children's brief delight, and then see the remorseless pencil do its fatal work. I often joined my supplications to the children's for mercy . . . and pretended to be earnest. They were deceived as so was their mother . . . But it was very delightful, and I could not resist the temptation . . . Then I privately struck the passage out myself" (Hearn xxvii)

Richard Watson Gilder of the Century "deleted references to nakedness, offensive smells, and the blowing of noses; such a phrase as 'both of them took on like they' lost the twelve apostles' was suppressed, perhaps for fear of being perceived as blasphemous. Under Gilder's blue pencil, 'such a sweat' became 'such a hurry,' 'wet cloth' become 'shroud.' [. . .] Oddly, no one thought of deleting the vulgar word 'nigger.'" (Hearn xxxi) "'Mr. Clemens has great faults,' the cautious editor admitted; 'at times he is inartistically and indefensibly coarse . . . there is much of his writing that we would not print for a miscellaneous audience. If you should ever carefully compare the chapters of Huckleberry Finn, as we printed them, with the same as they appear in his book, you'll will see the most decided difference. These extracts were carefully edited for a magazine audience with his full consent" (Hearn xxxi)

Given this, it's surprising that while "He did not approve of swearing before women and children[, h]e also recognized that 'in certain trying circumstances, desperate circumstances, urgent circumstances, profanity furnishes a relief even to prayer'" (Hearn xxxiii).

Marketing the book:

The publisher's write up assured potential readers that HF was "written in Mark Twain's old style" "a cure for melancholy." It was marketed as a " humorous book with 'side-splitting stories, sly hints at different weaknesses of society, and adventures of the most humorous description" "Nine-tenths of our ills are due to an over-burdened mind and overtaxed brain, or imaginary troubles that never come. An amusing book is a panacea more agreeable than medicine and less expensive than doctors' bills" "a book for the young and the old, the rich and the poor" (Hearn lxvi-vii)

See facsimile of advertising below.

And on the "N" word controversy: see this commentary from the Daily Show

The Times

Note: novel takes place in the 1840s.

Image from The Annotated Huckleberry Finn, ed. Michael Hearn. Page 2

Racial views in the North? Glad you asked."In 1835, three young black men traveled from New York City to attend a school established by abolitionists in the town of Canaan, New Hampshire. 'Fourteen black boys with books in the hands set the entire Granite State crazy!' recalled the minister Alexander Crummell, for whites 'could not endure what they called a 'Nigger School' on the soil of New Hampshire''" (Hodes 74-75). Crummell was one of the boys.

Hodes,

Martha. The Sea

Captain's Wife. Norton, 2006.

For Jim's point of view, consider these letters from slaves written to their former masters after the Civil War: "The painful, cutting and brilliant letters Black people wrote to their former enslavers"

And for the novel's connection to America today (circa 2020s), see Predictive Satire: Literary Intelligence, Mark Twain, and 21st Century Hucksters, a paper delivered at the Ninth International Conference on the State of Mark Twain Studies, August 2022.

See also Twain's own

Violence in the South

The violence in the novel (sure to earn it a M rating today) is part and parcel of life in the South.

The English writer, Frederick Marryat, touring antebellum America (when Huck Finn is set), wrote in his diary that "Every crime increases in magnitude and proportion as it affects the welfare and interest of the community [ . . . .] Of punishments, it will be observed that society has awarded the most severe for crimes committed against it, rather than those that offend God. Upon this principle, in the Southern and Western States, you may murder ten white men and no one will arraign you or trouble himself about the matter; but steal one nigger , and the whole community are in arms, and express the most virtuous indignation against the sin of theft, although that of murder will be disregarded" (234).

And consider the following quotes from David Grimstead's Mobbing in America (great title)In the South,

And finally, Twain himself, in a 1901 essay he considered too inflammatory to publish, excoriated his Southern brethen's natural recourse to violence. The essay, "The United States of Lyncherdom," saw print only after his death. This reluctance to directly challenge the racist ideologies explains, in part, the evasions, satire, and irony of Huck Finn. It also results in a font of humor.

For short histories of lynching in America, see "About Lynching" on the Modern Poetry web site.

Day 1:

The N word; Publishing history (see bottom of lesson plan for

photo); historical context; middle class; opening chapters;

southern violence; race; the civil war;

Day 2:

Violence (see above); Appearances v. reality; Arcadia; race; duke

and dauphin; the ending (Ah! Romance!)

- Main characters: Huckleberry Finn, Jim, Tom Sawyer, Widow Douglas, Miss Watson, Pap (119, 120) Duke and Dauphin

- Contrast Sut Lovingood with HF

- What do you make of the title page? Why so much information?

- When does the Widow Douglas decide to take him in? What happens to him first? (Chap 1; 109) ; what does she want to do to him?

- What does the observation that while she objects to tobacco, Miss Watson takes snuff say about Huck? (Chap 1; 109)

- What do you make of Tom's oath? (Chap 1; 112)

- Since he's an outlaw, he trusts only his own ideas? (113) Where does Tom derive his knowledge from? "Don't I tell you it's in the books? Do you want to go to doing different from what's in the books, and get things all muddled up?" (113)

- Chap IV -- how is Jim presented? (119)

- Chapter VI How is Pap's speech about the "mulatter" ironic?

- Victorian values "taught people to work hard, to postpone gratification, to repress themselves sexually, to 'improve' themselves, to be sober, conscientious, even compulsive" (Howe 521). Who embraces these values? Who rejects them? How is the pursuit of these values portrayed in the novel -- positive or negative? How does this compare/contrast with Ragged Dick ?

- Now given the values above, why would so many institutions get so worried and upset about this novel? As late as 1905, HF (and even Tom Sawyer) was excluded from the Brooklyn public library. Why?

- Given this quote "This was the age of faith. We were as sure of God as we were of the sun. Christmas had a reality that clutched us hard; we were of it, and it was us." (Reese 5) from Lizette Reese's Victorian Village, what would many readers think of HF? Is it "sure of God"? Go to particular scenes and view them from a religious perspective. What is Twain "saying" about religion?

- Does this have any connection to Rebecca Harding Davis's "Life in the Iron Mills"?

- Is the raft scene needed? (Chapter XVI 161-169)

- Who is literally the whitest person in the book? (119) "In terms of the racial politics of the novel, Pap's 'whiteness' is exactly like any other southern man's, just a more extreme version of it" (Messent 76) Is this true?

- How does Huck resemble Dick Hunter? How is he different?

- Most children's books have morals; since this is a children's book, what's it moral?

- Clothes in Huck Finn : do they function in a similar manner than in Ragged Dick ?

- Bible in the scene with Bogg's being murdered -- note that it seems to take his life out.

- In a late unpublished (and grand) work title "The Mysterious

Stranger," Satan says:

It is true, that which I have revealed to you; there is no God, no universe, no human have revealed to you; there is no God, no universe, no human race, no earthly life, no heaven, no hell. It is all a dream--a grotesque and foolish dream. Nothing exists but you. And you are but a thought--a vagrant thought, a useless thought, a homeless thought, wandering forlorn among the empty eternities!

He vanished, and left me appalled; for I knew, and realized, that all he had said was true.Much has been made of the turn in Twain's worldview; how he turned from the humorous writer of children tales to a darker, more pessimistic view of man. But some critics are saying "Not so fast. This darker vision was there all along." Do you see this darker vision in HF or is it just to sunny on the river?

- Of course a central question today is the use of the word nigger and the treatment of Jim. Can a work be considered to represent a nation and use language that is now considered inflammatory? Is this, ultimately, a racist novel or a novel against racism?

- When does Huck begin to realize Jim is, indeed, a person? Why? What accounts for the change? At what points later in the novel does he acknowledge this as well?

- That said, consider the following line from HF "He was the easiest nigger to laugh that ever was, anyway" (chap. XX). Twain originally wrote 'fellow' in the manuscript (Hearn 226). Why change it to "nigger"?

- Are the differences between Huck's lies and, say, the Duke and Dauphin's lies?

- What are the differences between the Duke and Dauphin as characters? Why not have them the same? What does Twain gain by making them different?

- Who's the most striking performing in the circus? (Chapter XXII) What symbolic meaning could this performer have? Could he echo other characters in the novel?

- A Georgian girl, from a school composition titled "Things that I Love," penned a rhapsody to graveyards which mirrors Nell's passion: "I love to walk in the graveyard, and read the inscriptions on the tombstones, the weeping willows fall so gracefully over the silent dead; here and there you may see a rosebush, or a bed of violets, planted and trained by some gentle hand over a dead friend" (Saum 91). Who does this remind you of in the novel?

- "It is a law that humor is created by contrasts [wrote Twain in 1891 . . .] It is the legitimate child of contrast" (qtd. in Hearn xcviii). Do we see this "law" in Huck Finn ?

- Harry Thurston Peck 1910: "It is only short-sighted persons who talk of Mark Twain's profound 'philosophy of life,'" "He had no philosophy of life, any more than a Fielding had or Steele or Harte. But like them he had an instinct for pure humor, which was most effective when it was unconscious" (qtd. Hearn cxxix). Two points here: one on Twain's "philosophy" (i.e. is he saying we should follow a particular emotional/social/intellectual path) of life, and one on his humor, which to Peck seems accidental. Can you peck on Peck? Can you show that he does, indeed, suggest a philosophy of life in HF? Can you find a method to the madness that is his humor?

- Michael Hearn argues for the centrality of the "Moses and the

Bulrushers" section of the novel. He writes that

This casual reference to Exodus 2:3-10 introduces a central theme to the novel: Like Moses who freed the Israelites from bondage in Egypt , so too does Huck Finn aid a Southern slave in this flight from his master. Both outlawed boys escape by a river. Moses in an ark of bulrushes on the Nile, Huck by raft down the Mississippi . And both are wards of women of the upper class, the slave-owning class. This scripture especially appealed to slaves who knew that one day they too would be liberated. 'Go down, Moses!' they sang. 'Tell Pharaoh, let my people go!' Ironically, although he led his own people out of bondage, Moses provided for slavery among the Israelites in Exodus 21; and it was this holy ordinance that Southern slaveholders clung to as proof that God not only sanctioned but ordered their system of servitude" (Hearn 19)

Is this too much to hang on one idea/quote or does this work? What does this short (relatively speaking) quote reveal about interpreting literature?

- Huck is "reborn" several times: towards end of novel he states "it was like being born again." Why?

- Peter Messent, in the very good (and short) The Cambridge Introduction to Mark Twain, argues that Twain "addresses themes and issues of vital relevance to his own time; the impact of modernization and what it meant to previous ideas of human agency (the authority to control and direct one's own fate); the changing racial landscape and the problems associated with it; anxieties about business values and masculinity in an era of capitalist expansion" (16). Do find all of these elements in HF?

- What's the name of the wrecked steamboat in

- Note the description of the Grangerford's house in chapter XVII (177) -- how is that description ironic? How does Huck judge the house? What impression do reader's get from his description?

- Irony/Satire: What's the purpose of the church scene in the Grangerford chapters? (Chap XVIII 183)

- Regionalisms: Leslie Fiedler sees homo eroticism in Jim's reference to Huck throughout the novel as "honey" (187). Is this an accurate reading?

- Note last line of Chapter XVIII -- what words seem "loaded"?

- How does Huck view Colonel Grangerford? How does Twain want readers to view him? (Chap XVIII)

- Take a close look at the structure of Chapter XIX (187). How does it open? What's the tone? What mood does it set? When is this mood broken? What does Twain suggest by this?

- Describe the human/social relations/interactions as Huck and Jim move deeper into the south. Do they change?

- Many critics argue the final evasion chapters constitute a falling off of the nobility of the novel, in particular in its treatment of Jim? Is this true, or is Twain using Jim's treatment as a metaphor/symbol?

- In Chapter VI, Pap calls Huck the "angel of death" -- given the rest of the novel, how is this true? 151,

- Why is Huck always making up stories?

- David Grimstead observes that "The South accepted extralegal structures parallel to its flourishing legal system in part because a slave society glorified mastery as its central honorific. Its extralegal systems, personal and collective, allowed Southerners to escape from situations of moral ambiguity and embarrassment into ones of melodramatically simple and dead certain answers" (America xi). Do you see this played out in the novel?

- Appearances v. Reality

American culture has a long history of reveling in the disjunct between appearances and reality. Sometimes, people are confused by them -- as when poor white farmers supported (with their lives) a system -- slavery -- that ensured their poverty. As we've seen in Ragged Dick, con men (usually urban wits) roamed the streets, ready to take in dupes (often country bumpkins). Herman Melville published The Confidence Man in (1857) exploring some of these ideas. The modern critic Karen Halttuen explores this territory in Confidence Men and Painted Women, though her focus is primarily on antebellum America.

2 questions:

1) how is this idea of the differences between appearances and reality apparent in the novel? How many discrepancies can you pick up on?

2) Why do this? What is suggested by this? - Consider the violence of chapter XXI; what's it doing in a children's book? And more generally, what is Twain suggesting about the culture by including this episode -- and note it bleeds into the next chapter (don't stop just at the shoot out). For starters, consider the following from Frederick Marryat's 1839 diary "Every crime increases in magnitude and proportion as it affects the welfare and interest of the community [ . . . .] Of punishments, it will be observed that society has awarded the most severe for crimes committed against it, rather than those that offend God. Upon this principle, in the Southern and Western States, you may murder ten white men and no one will arraign you or trouble himself about the matter; but steal one nigger , and the whole community are in arms, and express the most virtuous indignation against the sin of theft, although that of murder will be disregarded" (234).

- Why does Huck light out for the territories at the end of the novel? What is Twain suggesting?

Works Cited

Hearn, Michael, ed. The Annotated Huckleberry Finn. New York : Norton, 2001.

Marryat, Frederick . A Diary in America: With Remarks on Its Institutions. Vol. 1. London : Longman, Orme, Brown, Green & Longmans, 1839.

Messent, Peter. The Cambridge Introduction to Mark Twain. Cambridge UP, 2007.

Group Questions

Remember to include quotes from the readings to support

your answers

Day 1

- Victorian values "taught people to work hard, to postpone gratification, to repress themselves sexually, to 'improve' themselves, to be sober, conscientious, even compulsive" (Howe 521). Who in the novel embraces these values? Who rejects them? How is the pursuit of these values portrayed in the novel -- positively or negatively? How does this compare/contrast with Ragged Dick?

- And speaking of Ragged Dick . . . how does Huck resemble Dick Hunter? How is he different?

- Chapter VI How is Pap's speech about the "mulatter" ironic?

- Note the description of the Grangerford's house in chapter XVII (177) -- how is that description ironic? How does Huck judge the house? What impression do reader's get from his description?

- Michael Hearn argues for the centrality of the "Moses and the

Bulrushers" section of the novel. He writes that

This casual reference to Exodus 2:3-10 introduces a central theme to the novel: Like Moses who freed the Israelites from bondage in Egypt , so too does Huck Finn aid a Southern slave in this flight from his master. Both outlawed boys escape by a river. Moses in an ark of bulrushes on the Nile, Huck by raft down the Mississippi . And both are wards of women of the upper class, the slave-owning class. This scripture especially appealed to slaves who knew that one day they too would be liberated. 'Go down, Moses!' they sang. 'Tell Pharaoh, let my people go!' Ironically, although he led his own people out of bondage, Moses provided for slavery among the Israelites in Exodus 21; and it was this holy ordinance that Southern slaveholders clung to as proof that God not only sanctioned but ordered their system of servitude" (Hearn 19)

Is this too much to hang on one idea/quote or does this interpretation work? What does this short (relatively speaking) commentary reveal about interpreting literature?

Day 2

- Peter Messent, in the very good (and short) Cambridge Introduction to Mark Twain, argues that Twain

addresses themes and issues of vital relevance to his own time; the impact of modernization and what it meant to previous ideas of human agency (the authority to control and direct one's own fate); the changing racial landscape and the problems associated with it; anxieties about business values and masculinity in an era of capitalist expansion. (16)

Do find all of these elements in HF?

- In a late unpublished (and grand) work by Twain titled "The Mysterious Stranger," Satan says:

It is true, that which I have revealed to you; there is no God, no universe, no human have revealed to you; there is no God, no universe, no human race, no earthly life, no heaven, no hell. It is all a dream--a grotesque and foolish dream. Nothing exists but you. And you are but a thought--a vagrant thought, a useless thought, a homeless thought, wandering forlorn among the empty eternities!

He vanished, and left me appalled; for I knew, and realized, that all he had said was true.

Much has been made of the turn in Twain's worldview; how he changed from the humorous writer of children tales to a darker, more pessimistic view of man. But some critics are saying "Not so fast. This darker vision was there all along." Do you see this darker vision in HF or is it just too sunny on the river?

-

Harry Thurston Peck 1910: "It is only short-sighted persons who talk of Mark Twain's profound 'philosophy of life,'" "He had no philosophy of life, any more than a Fielding had or Steele or Harte. But like them he had an instinct for pure humor, which was most effective when it was unconscious" (qtd. in Hearn cxxix). Two points here: one on Twain's "philosophy" (i.e. is he saying we should follow a particular emotional/social/intellectual path) of life, and one on his humor, which to Peck seems accidental. Can you peck on Peck? Can you show that he does, indeed, suggest a philosophy of life in HF? Can you find a method to the madness that is his humor?

-

Of course a central question today is the use of the word nigger and the treatment of Jim. Can a work be considered to represent a nation and use language that is now considered inflammatory? Is this, ultimately, a racist novel or a novel against racism?

- Many critics believe that this is a flawed novel: that the demeaning treatment of Jim at the end of the novel, mitigates its attacks against social ills or more broadly that the structure of the story falls apart and its narrative impulse just peters out. Do you agree? Do the final scenes on the farm with Tom and Huck and Jim "fit" with the rest of the novel? Does the novel "hold together" at the end? How or how not (and yes, I know "how not" doesn't make sense but it seemed too good to resist)?

Center for Mark Twain Studies

Both a place and site - good starting point for further research.

Radio

essay on con men in America

On the Media, March 6, 2009: "The Confidence Man"

Mark

Twain in His Times

An example of what the web is capable of -- in short, superb.

Mark Twain on PBS

Companion site to the Ken Burns documentary. Filled with photos

and information.

Mark Twain Papers and

Project

Letters, essays, etc.

University

of Virginia Huck Finn Homepage

One of the best sites on the novel itself.

Illustrating

Huckleberry Finn

Fascinating site which shows all of the illustrations and includes

additional information on race, etc.

Pictures, Pictures, Pictures

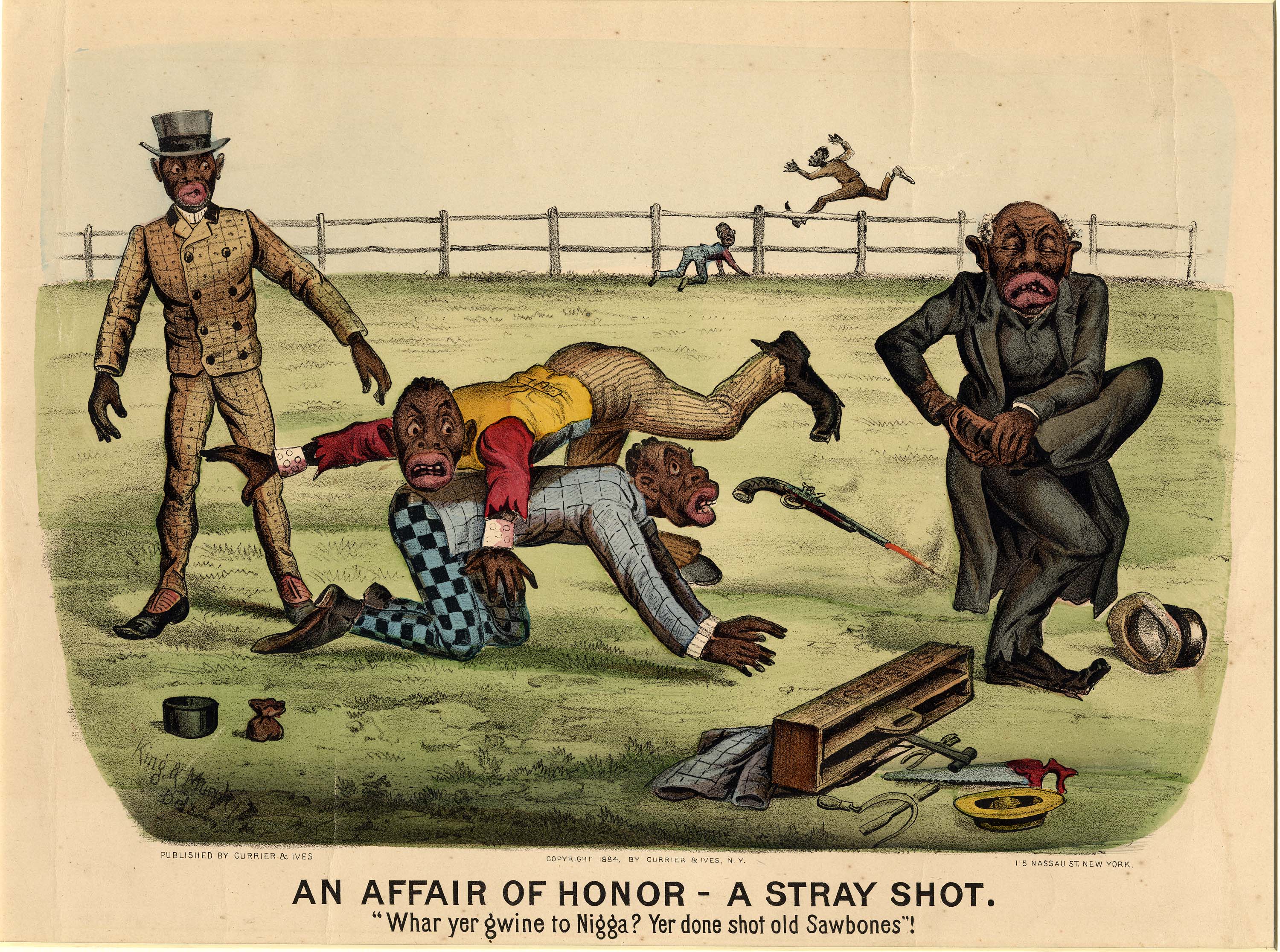

Currier and Ives, the most esteemed and respected

lithographer of the day, best known now for their beautifully

detailed and panoramic prints of cities and of the halcyon days of

Victorian America, also published a "Darktown" series, filled with

blatant stereotypes of African Americans. It's instructive in

understanding the representation of Jim in the novel, and how he,

at times, almost seems a caricature of a caricature: Twain seemed

to consciously model him on a minstrel Negro, which was itself a

caricature of an actual Negro.

Below is a print from the Darktown series and a link to a an online exhibition of the series.

The title page of the novel -- see link at the top of this page for a link to the illustrated novel.

Advertisement: travelling salesmen would bring this to prospective buyers.

When Huck was using the Bible in the Solomon episode, it "may seem to be gratuitous to the action of the story, it nevertheless repeats an important theme of the novel, that one's morality must come naturally from within oneself (as it does with Jim here) and not from some abstract set of values or from some 'authority' (as with Huck)" (Hearn 140).

Sunrise scene Chapter 14: "The trouble lies not with Nature but with Man. The boy explores all five senses: sight (pale landscape); sound (bullfrogs' chattering); smell (fragrant breezes); taste (fish breakfast); and touch (swimming nude). Man need only enjoy and stop fighting the river to discover its wonders. But those on the land cannot be bothered. They are too busy cheating their customers or killing gars or swearing to share Huck and Jim's communion with the Mississippi . Never on the raft are Huck and Jim entirely free of the threat of 'sivilization.' It lurks around every bend in the river. So long as the fugitives stay on water and away from land they are safe; they need not leave Eden" (Hearn 205).

"There has been much critical debate as to whether Jim is represented as a demeaning minstrel stereotype (the racist representation of the African American as uneducated, simple-minded, insensitive and unfailingly cheerful, common in all forms of popular entertainment in the period), or whether he is [83] presented as an intelligent and clear-thinking adult determinedly looking to bring himself to as full a freedom as can be gained in the America of his time" (Messent 83)

Consider the oppositional structure of the novel "black and white, instinct and impulse and social belonging and learned language, river and shore, raft and permanent 'home,' civilization and wilderness, child and adulthood, male and female, slavery and freedom" (Messent 114)

© David Bordelon 2009