Lesson Plans

Course Links

Lesson Plans

Course Documents Links

Secondary Sources

Quick Links

Library Links

Citing Sources

The Awakening

Kate Chopin

1899

Terms | Life | Times | Class Discussion | Group Questions | Links | Pictures

image source

www.vcu.edu/engweb/ webtexts/hour/chopin2.gif

Terms to Know

Gilded Age:

The name given to late 19th century America, denoting a time when

fortunes were made (by a few) and capitalism was the reigning law of

the land and the epitome of the American Dream. Twain, who with Charles

Dudley Warner wrote a novel (1873) giving the age its name, believed

that the supposed golden times were all surface ("gilded") which hid a

system that enshrined a growing income inequality between the wealthy

and everyone else ("hey . . . that sounds familiar . . ."). The term

has come to define a historical period when "Robber Barons"

(capitalists who exploited workers and worked the political system for

their own gain) ruled and workers suffered, but when most of the

middle-class thought all was well ("hey . . . they're playing that song

again").

This term has a scientific component both in the technologies that allowed capitalists to accrue fortunes (trains, smelting, oil drilling, etc.) and in the adoption of Darwin's theory of evolution to apply to human relationships: social darwinism: aka the survival of the fittest. Those who believed in social darwinism argued that the titans of capital naturally rose to the top of the evolutionary food chain (the help of rigged trading schemes, corrupt government officials, monopolies, violence, etc. was conveniently ignored) and thus deserved their spoils.

For a more detailed (and very good) explanation of this term, see the "Gilded Age" essay in The Oxford Companion to American History.

"Conspicuous Consumption": this phrase, from Thorstein Veblen's Theory of the Leisure Class (1899) captures the feelings of the American love of "stuff" -- to use the comedian's George Carlin's term. An early social scientist, Veblen observed the ostentatious wealth of the Gilded Age with a gimlet eye. He understood that when people accumulate wealth, they often felt the need to parade it before others. Veblen writes that

The quasi-peaceable gentleman of leisure, then, not only consumes of the staff of life beyond the minimum required for subsistence and physical efficiency, but his consumption also undergoes a specialization as regards the quality of the goods consumed. He consumes freely and of the best, in food, drink, narcotics, shelter, service, ornaments, apparel, weapons, and accoutrements, amusements, amulets, and idols or divinities [today, of course, you'd have to add SUV's to the list]. . . . Since the consumption of these more excellent goods is an evidence of wealth, it become honorific; and conversely, the failure to consume in due quantity and quality becomes a mark of inferiority and demerit. (190)This connected to women of the time because it often fell upon them to "feather the nest" of the household. And as a conduct book of the period noted, when referring to the importance of dinner parties as a way up the social ladder,

It is needless to say to aspirants for social honors, who really wish to "entertain," that dinner-giving is a serious expense, and entails all sorts of obligations upon the embarkers in such an enterprise. (circa 1898; qtd. in Culley 125)Thorstein felt that for women (usually white, middle/upper-class), this "conspicuous consumption" (187) resulted in a kind of slavery, because they are often "the ceremonial consumer of goods" produced by husbands (195). The "vicarious leisure" of these women "almost invariably occurs disguised under some form of work or household duties or social amenities, which prove on analysis to serve little or no ulterior end beyond showing that she does not and need not occupy herself with anything that is gainful or that is of substantial use" (194). Watch, in the novel, for evidence of this kind of busy-work mentality.

Local color: A term used to describe late nineteenth century America writers/artists who focused particular regions -- rural Maine for Sarah Orne Jewet; Louisiana rural life for Chopin -- to explore hitherto little known cultures, settings, and personalities. This fit into the vogue of travel writing that was so popular and into a burgeoning interest in the new field of sociology.

Gibson Girl: Starting as a series of drawings of women popularized by Charles Dana Gibson, this term came to symbolize the "New Woman" of the 1890s: liberated, emancipated, comfortable in the outdoors, self-confidence, beautiful, intelligent -- and, of course, middle to upper class.

Freud -- the Id -- Repression: Freud published his Interpretation of Dreams in 1900, so his ideas are in the air. As my heading suggests, consider two aspects of Freudianism here: the Id -- the instinctual, animalistic, and greedy part of our personality that we supposedly grow out of as an adult (note the supposedly); and repression -- the idea that if you hold back a deep yearning, it will manifest itself in an alternate manner or form.

The Life

Born

in 1850 into an Irish/French family in St. Louis, Chopin's life was

dominated by strong women who often had to assume a dominant role in

family affairs. Chopin herself, after her husband's death, had to

assume a similar role in her own life. Her upbringing, due to the

wealth of her parents, assumed the usual (for a white, upper-class

woman) progression from child to debutante to wife. By all

accounts, her marriage was a happy one, and she bore six

children. While she spent many years in Louisiana, and her

fiction is set there, she moved back to St. Louis in 1884, two years

after the her husband's death and it was while living there that she

began her literary career.

This

is one of the houses the Chopin's rented during the nine years they

lived in New Orleans. Located at 1413 Louisiana Ave., its style

and shape is similar to the house on Esplanade Ave. described in the

novel.

This

is one of the houses the Chopin's rented during the nine years they

lived in New Orleans. Located at 1413 Louisiana Ave., its style

and shape is similar to the house on Esplanade Ave. described in the

novel.

Her home in Natchitoches, LA, where she lived (happily?) in the 1870s and 1880s. (Image from http://www.city-data.com/picfilesv/picv8720.php)

As noted above, Chopin was known primarily as a writer of Local-Color short fiction, collected in Bayou Folk (1894), and A Night In Acadie (1897), and an earlier novel, At Fault (1890). While critics praised her earlier work for its "charm," most found the subject matter of The Awakening distasteful and immoral. Representative of the criticism is found in the following excerpt from the magazine The Outlook:

The Awakening is a decidedly unpleasant study of a temperament. The author, Kate Chopin, is known as the writer of several faithful stories of Louisiana life. This, too, is faithful enough in its presentation of certain phases of human passion and downward drift of character, but the story was not really worth telling, and its disagreeable glimpses of sensuality are repellent. (qtd. in Culley 166)Chopin responded to these reviews in an 1899 note published in Book News:

Having a group of people at my disposal, I thought it might be entertaining (to myself) to throw them together and see what would happen. I never dreamed of Mrs. Pontellier making such a mess of things and working out her own damnation as she did. If I had had the slightest intimation of such a thing I would have excluded her from the company. But when I found out what she was up to, the play was half over and it was too late. (qtd. in Walker 14).

Note that she doesn't apologize or accept the view that the novel is

immoral; instead, like any true artist, she treats Edna as a "real"

person, alluding to the creative powers of fiction and the muse-like

quality a powerful character exerts on a writer. It's as if Edna

somehow had a life of her own and Chopin was merely recording her

actions.An interesting sidelight to the criticism of the novel is

Chopin's love of Walt Whitman's poetry -- he of Song of Myself

with its "banned in Boston" notoriety. This, along which her interest

in contemporary French fiction (considered the "steamy romance" novels

of the period) may explain why she didn't shy away from depictions of,

as the reviewer above notes, "sensuality." For Chopin, sexuality

was not something to be repressed, but something that should be expressed,

at least in fiction (see her unpublished story "The Storm" for another

representation of sexuality in her fiction). Shortly after The Awakening was published, Chopin health declined, which contributed to her withdrawal from the publishing scene. She died in 1904.

Back to top

The Times

The actions of the novel occur during the height of American Victorianism, a time when people (even some of the pious) embraced Social Darwinism; when Jim Crow

legislation put the imprimatur of law on segregation; and when piano

legs had little aprons around them to hide phallic associations.

Obviously, the word "repression" comes to mind, and this repression

extends along racial, class, and gender lines. Set in New Orleans

and the resort community of Grand Isle some hundred miles south, the

novel is rooted in the social mores and traditions of the "Crescent

City." New Orleans, one of the oldest cities in America, still

operated (and operates) on a class system. The wealth landowners

and "old money" inhabitants made up the ruling aristocratic class and

worked assiduously to preserve their power with an elaborate hierarchy

of family alliances and connections, reinforced by marriages, parties,

and summer homes. This power base even had a gendered quality:

for women it entailed "receiving calls" from other women, and for men,

it entailed membership in the proper "club." Laid over the existing

class system was a peculiarly Southern concern about race, and in

particular, blood lines.

Though the Civil War ended about forty years before the events that take place in the novel, the class system that the antebellum planter system supported was still, for the most part, in place. As the descendants of Thomas Jefferson can tell you, slavery made for, if you'll pardon the pun, strange bedfellows. The power relationship between master and slave meant that slaves had little or no defense when it came to warding off the sexual predations of their owners. The result, a mixture of skin tones ranging from olive to a rich, dark, blue-black, conjured up fearful visions of a mongrel race, complete with physical and mental degradation. The concern over this "miscegenation" lead to birth certificates attesting to percentages of Negro blood resulting in a discourse of race -- including terms like octoroon, quadroon, and mulatto -- which was used as a linguistic barrier to prevent class and blood lines from being mixed.Of course a Freudian critic would point to these anxieties as a kind of repression of the fear that everyone's blood was tainted: i.e., an unconscious fear that if you looked deeply enough into any of the upper-classes bloodlines, you would find a drop or two of Negro blood. This fear and anxiety about place and social status, though more directly addressed by Chopin in her short story "Desiree's Baby," manifests itself in the novel by the attention the characters pay to the subtleties of class distinctions, the gradations in the social pecking order between Anglo-Americans, Europeans, Creoles, Cajuns, and Colored people. For members of the upper-class, a fall from one economic class meant a corresponding fall from a social class -- and the uncomfortable prospect of being on a social par with the Other -- the group you previously kept at arm's length.

Being a predominately patriarchal culture, women could be considered another kind of Other -- particularly those women who tried to assert their rights."The Woman Question," as it was labeled in nineteenth-century America, entailed everything from women's suffrage to the cultural prohibition against women smoking in public. Louisiana, with its Napoleonic Code of law, made it especially difficult for women to assume an identity independent from their husbands. Though originally designed to protect women, the Code meant that they were not allowed to hold separate property after marriage and transferred all rights to the male. Essentially, it relegated women to a chattel slave status, as the property of their husbands. The legal status of women in Louisiana is tellingly illustrated by Article 1591 of its State Code:

The following persons are absolutely incapable of bearing witness to testaments: 1. Women of any age whatsoever. 2. Male children who have not attained the age of sixteen years complete. 3. Persons who are insane, deaf, dumb or blind. 4. Persons whom the criminal laws declare incapable of exercising civil functions. (qtd. in Culley 120)Notice, of course, the company women are placed in.The lives of women -- especially of the middle and upper-class -- were circumscribed by an elaborate system of manners and customs designed to shield them from the world outside the home. These customs were promulgated by a variety of "conduct books" which offered guidelines to ensure "proper" behavior. The samples below can give you an idea of the role of women in the society.

What the child needs pre-eminently above playthings, books, clothes, and every other earthly thing, is the presence and influence of mother. . . . Many otherwise excellent women find the nursery a prison, and the care of their own children irksome, simply because they have a perverted mother-sense. The mother should have proper relief from the care of her children, but if she has the true mother-heart the companionship of her children will be the society which she will prefer above that of all others. (circa 1897; qtd. in Culley 123)

Let nothing, but the most imperative duty, call you out upon your reception day. Your callers are, in a measure, invited guests, and it will be an insulting mark of rudeness to be out when they call. Neither can you be excused, except in case of sickness. (circa 1860; qtd. in Culley 123)

The true lady walks the street, wrapped in a mantle of proper reserve, so impenetrable that insult and coarse familiarity shrink from her, while she, at the same time, carries with her a congenial atmosphere which attracts all, and puts all at their ease. (circa 1882; qtd. in Culley 125)

Do not accept an invitation to visit any place of public amusement, with a gentleman with whom you are but slightly acquainted, unless there is another lady also invited. (circa 1860; qtd. in Culley 125)

These prohibitions were all designed to reinforce the prevailing cultural ethos of woman as mother, woman as ornament, and woman as angel, an arrangement which effectively limited woman's role to a caretaker status and helpmeet to man. Above all, as the last two excerpts show, women's sexuality was denied.Yet though all the culture pressures were bent on shaping women into desexed and dependent beings, some women sought to throw off the yoke of social conformity. From around 1848 (Seneca Falls Convention) on through today, women have agitated for change. By the end of the nineteenth-century, when the story takes place, women were agitating for "self-ownership" -- the right of control over reproduction. The argument went that since women bore the burden childbirth and its attendant care of children, they should decide when and if they wanted to become pregnant. Since birth control was deemed unacceptable by most women, the decision to control reproduction usually meant abstinence. It also meant the women could derive a measure of independence by exerting control over their bodies and thus, control over their destinies.

But there is a difference between what "guidebooks" suggest and what is actually occurring in a society. Carl Degler exposes a much more nuanced and open view of nineteenth century sexuality in "What Ought To Be and What Was: Women's Sexuality in the Nineteenth Century." Give it a quick run through for a balanced approached to individual views of sexuality during the time period. For a less scholarly overview of the same material, see Kara Platoni's "The Sex Scholar" Stanford Magazine March/April 2010.Consider also this essay on "A Woman's Plea for Woman" by Felcia Holt published in The Ladies Home Journal in 1889.

And finally, In 1889, the editors of the magazine The North American Review posed a series of questions regarding women and divorce to a variety of influential writers and thinkers (including Rebecca Harding Davis). Some of the results are below.

"Are Women to Blame?" by Rebecca Harding Davis, et al.; "Unhappy Marriages in Fiction" by Andrew Lang; and an essay on Divorce by a Bishop and Ingersoll Rand.

These essays supply a starting point for an examination of contemporary views of Edna's predicament.

The Arts

The maps above are there for a purpose: this novel is rooted firmly in its place: Louisiana. Before The Awakening was published, Chopin was known primarily as a regional writer of the "Local Color" school. This school amounted to a kind of anthropological travelogue, a narrative which includes detailed description of the setting, people, and customs of a particular region. The South, in general, and New Orleans in particular, was associated with a more relaxed way of life, an area more given to enjoyment of life than the Puritan North. It was also a place of artistic refinement: New Orleans could boast America's first opera house, and its architecture was noted the world over. More generally, New Orleans connotes the exotic, a steamy region of languid heat and a heterogeneous population, which led to a rather tolerant view of vices such as prostitution, gambling, and drinking.The other locale in the novel is the resort area of Grand Isle. Pay attention to the distinctions between the wide-open spaces (and especially water) of this Gulf of Mexico hideaway, and the city.

In

other fields, it's important to remember that the late 19th and early

20th century were a period of intensive change and experimentation in

art. Below find a picture entitled Moving Water (1898) by the Austrian painter Gustav Klimt which seems to echo the connections between water and the female in The Awakening.

I've always found an affinity between Impressionism -- artists who instead of striving for realism, strove to convey the effect of light as it created a, well, impression on their visual senses -- and Chopin. She seems to borrow this technique in her fiction, though instead of light, she uses words to convey the the world around her as well as the fleeting sensations that flicker in the minds of her characters. And like the Impressionists, capturing such evanescent qualities results in many shadows.

Like water, music runs throughout the novel. Chopin's Impromptu, and Isolde’s love song from Richard Wagner’s opera, Tristan and Isolde. The romantic sweep of these pieces are well suited to the romantic temper of Edna.

Works Cited

Culley, Margo. Editor. The Awakening. New York: Norton, 1976. Print.

Veblen, Thorstein. "Conspicuous Consumption." The Consumer Society Reader. Ed. by Juliet B.

Schor and Douglas B. Holt. New York: The New Press, 2000. 187-204. Print.

Walker, Nancy. Introduction to The Awakening. New York: St. Martin, 1993. 3-18. Print.

Class Discussion

Spoiler Alert -- some of the questions and comments here will give away the plot of the novel.

- When does the novel start (month)? When does the novel end? How many months is this?

- What is Mrs. Ratignolle's condition throughout the novel? What happens to her at the end of the novel?

- When Chopin first conceived the novel, she called it A Solitary Soul, but she later changed it to The Awakening. Consider these two things: 1) Why? What's the difference between Solitary Soul and Awakening? And why the more general The Awakening instead of Edna's Awakening?

- What is her "awakening"? What different "Awakenings" can you find? Can we categorize them? Be specific -- point out to passages in the text which support your views.

- What is meant by the line "the inward life which questions and the outward existence which conforms"? Note difference between life and existence -- why?

- The cultural details: Why is Edna reading "Emerson" 591; why does Madam Riesz play "Isolde's song" (584)

- Why won't Edna go to her sister's wedding? (588 "lamentable spectacles")

- Why the repetition of padded shoulders with Edna's father? 587

- What do the first exchanges b/t Leon and Edna, and the narrator's description of their relationship suggest (Even Leon's first words)? What is Leon's attitude towards his wife -- how does he regard her?

- What was Edna's father's advice to Leon concerning his relations with Edna? (590) -- What had it done for him? Why do you think Chopin included this seemingly inconsequential exchange? What does it illustrate?

- How does the theme of dream v. reality fit into this novel? Consider, for example, Edna's dream and the reality of the return of Robert (611) and her remarks to Dr. Mandelet "The years that are gone seem like dreams -- if one might go on sleeping and dreaming -- but to wake up and find -- oh! well! perhaps it is better to wake up after all, even to suffer, rather than to remain a dupe to illusions all one's life" (621) -- which is the dream world, and which is the real world for Edna? Is she a romantic -- and what does this entail??

- What does the sea symbolize in the novel? Consider 543, 544, 58 and 624"The water of the Gulf stretched out before her, gleaming with the million lights of the sun. The voice of the sea is seductive. . ."

- What are some of the themes of The Awakening?

- Let's play "Read the author's mind." Are Edna's actions, from the narrator's point of view, positive or negative?

- What is Chopin saying about Fate in the novel?

- What is Chopin saying about the "self;" and how did conceptions of the self cause problems in nineteenth-century America (in particular, for women)

- Could this novel be read as a depiction of the plight of the artist in America? Why?

- Why does Edna feel ill in the church? Why leave it? (562 chap XIII)

- Point out different passages where Chopin stresses the differences between Edna and other women in her society. What are some of these differences, and why is Edna different?

- What does Edna think of when Mme. Ratignolle plays the piano (chap 9)? What does she think of when Mme. Reisz plays (chap 9 and later)? What's the difference/similarity? How does each contribute to our understanding of her character?

- Symbolically, what do Mme. Ratignolle and Reisz represent in the novel? What do they represent to/for Edna?

- Why is Edna so moved by Chopin's music? Why does Chopin choose Chopin and not another composer?

- What is Edna's attitude towards sex at the beginning of the novel? How can you tell?

- What is Edna's relationship with her children? Does she fit her society's role of a "good mother?"

- What kind of woman does Mrs. Ratignolle represent (and how can you tell)? Why is she friendly with Edna? Why does Edna "pity" (56) her? Does this seem contradictory?

- What is the purpose of Mademoiselle Reisz's character in the novel? Consider, for example, her comment to Edna, after checking her shoulder blades, "The bird that would soar above the level plain of tradition and prejudice must have strong wings. It is a sad spectacle to see the weaklings bruised, exhausted, fluttering back to earth" (599). And consider the following on the same page: Arobin: "I've heard she's partially demented" -- and Edna's response: "She seems to me wonderfully sane" (600)

- Why is Edna "almost devoid of coquetry"? (588) -- doesn't it seem odd given Edna's passion? Why or why not?

- Why does Edna decide to remain naked at the end of the novel?

- Edna tells Arobin that "One of these days . . . I'm going to pull myself together for a while and think -- try to determine what character of a woman I am; for, candidly, I don't know. By all the codes which I am acquainted with, I am a devilishly wicked specimen of the sex. But some way I can't convince myself that I am" (599). Well, which is she? And more importantly, which does the author want you to feel she is? Is the author's feelings towards Edna apparent? How can you tell?

- Were you surprised by the ending? Why or why not?

- Connections to other stories? "Daisey Miller"? "The Open Boat"? How so?

- Consider the connections between the following sketch -- one of the first written by Chopin, and The Awakening.

Emancipation. A Life Fable There was once an animal born into this world, and opening his eyes upon Life, he saw above and about him confining walls, and before him were bars of iron through which came air and light from without; this animal was born in a cage. Here he grew, and throve in strength and beauty under the care of an invisible protecting hand. Hungering, food was ever at hand. When he thirsted water was brought, and when he felt the need to rest, there was provided a bed of straw upon which to lie; and here he found it good, licking his handsome flanks, to bask in the sun beam that he thought existed but to lighten his home. Awaking one day from his slothful rest, lo! the door of his cage stood open: accident had opened it. In the corner he crouched, wondering and fearingly. Then slowly did he approach the door, dreading the unaccustomed, and would have closed it, but for such a task his limbs were purposeless. So out the opening he thrust his head, to see the canopy of the sky grow broader, and the world waxing wider. Back to his corner but not to rest, for the spell of the Unknown was over him, and again and again he goes to the open door, seeing each time more Light. Then one time standing in the flood of it; a deep in-drawn breath -- a bracing of strong limbs, and with a bound he was gone. On he rushes, in his mad flight, heedless that he is wounding and tearing his sleek sides -- seeing, smelling, touching of all things; even stopping to put his lips to the noxious pool, thinking it may be sweet. Hungering there is no food but such as he must seek and ofttimes fight for; and his limbs are weighted before he reaches the water that is good to his thirsting throat. So does he live, seeking, finding, joying and suffering. The door which accident had opened is opened still, but the cage remains forever empty! |

Group Questions

Group Discussions: The Awakening

- Point out different passages where Chopin stresses the differences between Edna and other women in her society. What are some of these differences, and why is Edna different?

- What is Edna's attitude towards sex at the beginning of the novel? How can you tell?

- What is her "one propensity . . . " (547 or middle of chap 7)? What does it foreshadow?

- Chopin clearly makes Edna an outsider (as Mrs. Ratignolle tells Robert "She is not one of us; she is not like us" [549 or beginning of chap 8]) -- separate from the community of creoles of her husband and friends. Why? Why not have a women from within the community "Awaken"?

- What kind of woman does Mrs. Ratignolle represent (and how can you tell)? Why is she friendly with Edna? Why does Edna "pity" (578 or end of chap 18) her? Does this seem contradictory?

- What is the purpose of Mademoiselle Reisz's character in the novel? ("can I refuse you anything" 598+ middle of chap 26; and see 584) Consider, for example, her comment to Edna, after checking her shoulder blades, "The bird that would soar above the level plain of tradition and prejudice must have strong wings. It is a sad spectacle to see the weaklings bruised, exhausted, fluttering back to earth" (599 or beginning of chap 27). And consider the following on the same page: Arobin: "I've heard she's partially demented" -- and Edna's response: "She seems to me wonderfully sane" (600).

- How is Edna like Daisy Miller? How is she different?

2nd Group Discussion, The Awakening

- What is the role of "Fate" in this novel? Why, for instance, is it mentioned so many times (539, 548, 549, 553 and 616 chapters 3, 7, 35 )? What is Chopin suggesting about a person's ability to control their own destiny/actions, and how does this relate to the novel as a whole? Is this similar to the idea expressed in "The Open Boat"?

- What is Edna's relationship with her children? Does she fit her society's role (540, 548, 608-09, 620) of a "good mother?" Why does Madame Ratignolle tell Edna "think of the children" (621 or end of chap 37)? And why does this effect Edna so strongly?

- Why is Edna "almost devoid of coquetry"? (XXIII 615) -- doesn't it seem odd given Edna's passion? Why or why not?

- Why does Edna "want something to happen"? Did she really "not know what" (XXV 620)? If "Alcee Arobin was absolutely nothing to her" (XXV 622), why does Edna have an affair with him?

- Why does Robert leave instead of consummating his affair with Edna?

- The critic Elaine Showalter argues that "real and imaginary narcotics supplied by fantasy, money, and patriarchy . . . have protected Edna from pain for most of her life, but . . . have also kept her from becoming an adult" (184). Find specific examples of these "narcotics" in the text, and explain who each would "have protect[ed]" Edna. Also, is Showalter's assertion true? Is Edna suffering from arrested development?

- "She had resolved never again to belong to another than herself" (597 or middle of chap 26). Is this an important quote? Why or why not? And why does Edna later tell Robert: "If he were to say, 'Here, Robert, take her and be happy; she is yours,' I should laugh at you both'" (619 or end of XXXVI)?

- Edna tells Arobin that "One of these days . . . I'm going to pull myself together for a while and think -- try to determine what character of a woman I am; for, candidly, I don't know. By all the codes which I am acquainted with, I am a devilishly wicked specimen of the sex. But some way I can't convince myself that I am" (599 or beginning of 27). Well, which is she? And more importantly, which does the author want you to feel she is? Is the author's feelings towards Edna apparent? How can you tell?

- Why, when Edna is alone on the beach at the end of the novel, is there "A bird with a broken wing . . . beating the air above, reeling, fluttering, circling disabled down, down to the water" (624). And why did the novel open with a parrot?

- Why does she commit suicide?

"Conspicuous Consumption" reading

Pictures, Pictures, Pictures

Style Gallery 1897-99

1 - 1897 |

2 - 1897 |

3 - 1897 |

4 - 1898 |

5 - 1898 |

6 - 1899 |

7 - 1899 |

8 - 1899 |

- Madame Faydou wears her hair in a knot on top of her head. Her black gown and her daughter's grey dress (probably mourning attire) have fashionable leg o' mutton sleeves, 1897.

- Catherine Vlasto wears a white gown with puffed elbow-length sleeves and ribbon bows. Her hair is parted in the center and poufed casually at her temples, 1897.

- 1897 fashion plate shows an idealized form of the fashionable figure. The jacket has an asymmetrical closure and new, smaller sleeve puffs.

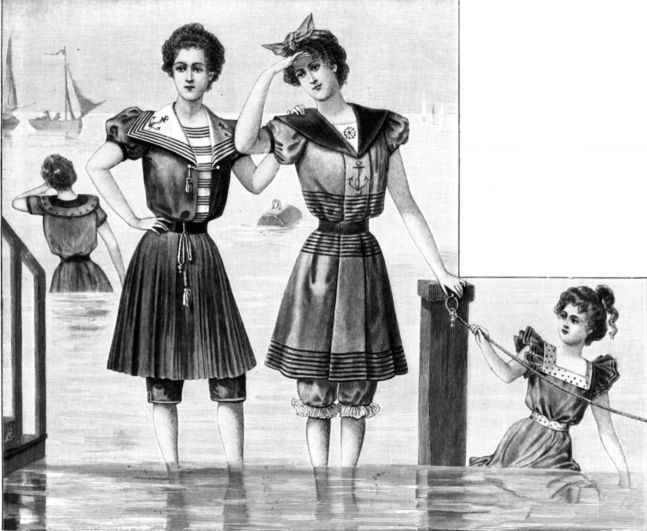

- Bathing costumes of 1898 have nautical details such as sailor collars.

- Gown of 1898 shows a short, wide puff at the shoulder over a long, tight sleeve.

- 1899 fashion plate shows the narrow, gored skirt and more natural shoulder of the turn of the century (as well as the results of "S-bend" corseting).

- Tea Gown of 1899 shows "Watteau back" and frothy trim.

- Two women in Watteau-backed tea gowns with high sashed waists, 1899.

from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1890s_in_fashion

Drunken Husband

Click to Enlarge

Image from

page 165 of Ames, Kenneth. Death in the Dining Room and Other Tales of Victorian Culture. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1992. Print.

Caption at bottom reads "The old old story was told again at 3 o'clock in the morning" (All caps in original)

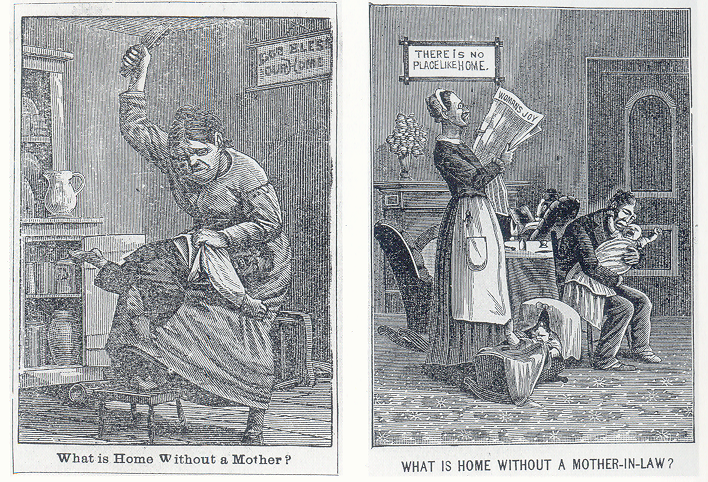

Comic postcards circa 1875-90. It appears the views of mother and motherhood were contested ground.

Image from page 116 Ames, Kenneth. Death in the Dining Room and Other Tales of Victorian Culture. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1992. Print.

© David Bordelon 2009