Lesson Plan

Lesson

Plans

Course

Documents

Links

Citing Sources

Writing

Center

Destiny: A Novel in Pictures | The System | Maus 1: My Father Bleeds History | Maus 2: Here My Troubles Began | Watchmen |Conpendium of Watchmen Questions and Notes | Ghost World | Lint

Throughout the semester, we'll be moving between form (the mechanics of the art form) and theme -- and how they complement each other.

We'll also be paying attention to semiotics -- or language as signs. In this case the language of comics.

Graphic Discourse: words used when describing graphic narratives

| Framing

(within the panel and the page) Panel (bottom row, right panel, second row) Strip (row of panels – or one long image) Gutter (spaces between panels, spaces in the spine) Bleeds (to describe an image or text which intrudes onto another panel or the gutter) Foreground Background Negative space |

Image |

Course introduction

Heider & Simmel animation (1944)

"Lunch Break" by Adrian Tomine

"Il revient et il bave" Online cartoon

Panels: naked.

Destiny: A Novel in Pictures

1930

Aesthetic/Historical/Cultural Background

- Hogarth's A Harlot's Progress

- Goats? Cultural meaning

Woodcut

Term applied to the technique of making a print from a block of

wood sawn along the grain and also to the print so made. Although

the term is often loosely used for any type of print made from

wood, it refers specifically to those made from blocks in which

the grain runs lengthways across the surface (as in a plank of

wood). It can thus be distinguished from wood engraving, in which

the print is made from wood sawn across the grain, producing a

surface capable of taking finer detail. Woodcut is the oldest

technique for making prints and its principles are very simple.

The design is drawn on a smooth block of wood (almost any wood of

medium softness can be used—beech, pear, sycamore for example) and

the parts that are to be white in the print are cut away with

knives and gouges, leaving the design standing up in relief. This

is then inked and the design printed on a sheet of paper. Cutting

blocks of any complexity is a highly skilled business and this

part of the work has often been done by specialist craftsmen

rather than the artist responsible for the design. Coloured

woodcuts, generally made by using a separate block for each

colour, have been particularly popular in Japan (see Ukiyo-e).

The origins of the woodcut are obscure (the principle was employed

in fabric printing in China at least as early as the 3rd century

ad). There is evidence that woodcuts as we know them were being

produced in Europe in the 14th century, but the earliest surviving

reliably dated example is perhaps the St Christopher (1423) by an

unknown artist in the John Rylands Library, Manchester. Many of

the earliest woodcuts were crude popular religious images designed

to be sold at fairs and pilgrim shrines (see also block book), but

in skilled hands the technique could produce much more

sophisticated results. It was at its peak in the first thirty

years of the 16th century, in both individual prints and book

illustrations, with Dürer being the supreme master. The connection

between woodcut and the art of the book was very close at this

time, as both used essentially the same method of printing and

therefore could be readily combined. However, in the course of the

16th century woodcut steadily lost ground to line engraving (which

required a heavier press but could produce finer detail and

subtler effects). By about 1600 woodcut was little used apart from

jobbing work and ephemera—broadsheets, chapbooks, playbills, and

suchlike—but in the late 19th and early 20th centuries there was a

major revival of interest in the technique as a medium of original

artistic expression. As photomechanical methods had now largely

taken over the reproductive functions of printmaking, all kinds of

hand engraving could make a fresh start. Gauguin and Munch were

the great pioneers in the 1890s, using the grain of the wood to

create bold and vigorous textural effects, and they were followed

by the German Expressionists (notably the members of Die Brücke),

some of whom virtually hacked the design into the block. See also

chiaroscuro woodcut.

Chilvers, Ian. "woodcut." The

Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists. Oxford University

Press, 2009. Oxford Reference.

2009. 23 Jan. 2016

http://www.oxfordreference.com.libproxy.ocean.edu:2048/view/10.1093/

acref/9780199532940.001.0001/acref-9780199532940-e-2659

From

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-E5Tzxo7O8J4/UWuWoZAyyMI/AAAAAAAAn

7E/M7BJYj0M-bE/s1600/Ex-Libris.JPG

Weimar Republic

"The republic of Germany formed after the end of World War I. On 9

November 1918 a republic was proclaimed in Berlin under the

moderate socialist Friedrich Ebert. An elected National Assembly

met in January 1919 in the city of Weimar and agreed on a

constitution. Ebert was elected first President (1919–25),

succeeded by Hindenburg (1925–34). The new republic had almost at

once to face the Versailles Peace Settlement, involving the loss

of continental territory and of all overseas colonies and the

likelihood of a vast reparations debt, the terms being so

unpopular as to provoke a brief right‐wing revolt, the Kapp

putsch. The country was unable to meet reparation costs, and the

mark collapsed, whereupon France and Belgium occupied the Ruhr in

1923, while in Bavaria right‐wing extremists (including Hitler and

Ludendorff) unsuccessfully tried to restore the monarchy. Gustav

Stresemann succeeded in restoring confidence and in persuading the

USA to act as mediator. The Dawes Plan adjusted reparation

payments, and France withdrew from the Ruhr. It was followed in

1929 by the Young Plan. Discontented financial and industrial

groups in the German National Party allied with Hitler’s Nazi

Party to form a powerful opposition. As unemployment developed,

support for this alliance grew, perceived as the only alternative

to communism. In the presidential elections of 1932 Hitler gained

some 13 million votes, exploiting anti‐communist fears and

anti‐Semitic prejudice, although Hindenburg was himself

re‐elected. In 1933 he was persuaded to accept Hitler as

Chancellor. Shortly after the Reichstag fire, Hitler declared a

state of emergency (28 February 1933) and, on Hindenburg’s death

in 1934, made himself President and proclaimed the Third Reich."

"Weimar Republic." A Dictionary

of World History. Oxford University Press, 2015. Oxford Reference. 2015. Web.

23 Jan. 2016.

Expressionism

"These two currents—the violent reworking of the world and the

embracing of abstraction—were to form the most distinct ways

forward in German 20th-century art. In the immediate aftermath of

the First World War, these dual tendencies may be seen in the

anti-art of the Dada movement and the formalist idealism of the

Bauhaus. The post-war years produced a mood of existential

disgust, expressed through an idiom of self-consciously ugly

realism. This is typified as much by the savage social satires of

George Grosz or the mordant dramas of Max Beckmann, as by the

overt social concern of Kathe Kollwitz's or Ludwig Meidner's

(1884–1966) images of poverty and deprivation. The artists of the

so-called Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), such as Otto Dix

and Christian Schad, painted stylishly deadpan works reflecting

the vital artistic ferment and bohemian fringes of the Weimar

Republic.

The rise of National Socialism brought this vibrant era to an

abrupt close. Within five years, German culture was effectively

extinguished and artists and their works made the object of

official abuse. This was symbolized by the 1937 Munich exhibition

of ‘Degenerate Art’. Many artists fled abroad, while others stayed

to work secretly on ‘unpainted paintings’, as Emil Nolde termed

his clandestine works. Their work was replaced by an anodyne

‘heroic’ romanticism, placed exclusively at the service of the

state."

From Morrall, Andrew. "German art." The

Oxford Companion to Western Art. Oxford University

Press, 2001. Oxford Reference.

2003. Web. 23 Jan. 2016.

"A pan-European movement in the arts—especially painting—that

developed in the first third of the 20th century. Rejecting

impressionism and naturalism, expressionism is anti-realist in

both approach and subject matter. It aims to ‘render visible’ (to

use one of its leading artists Paul Klee's famous phrase) that

which escapes representational painting, such as the raw effects

of emotion, sexuality and spirituality. Inspired by the writings

of the founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, which explore the

hidden world of the unconscious, expressionism wants to shed light

on the complex impulses underpinning daily life. The leading

figures of this movement were the Viennese painters Gustav Klimt

and Egon Schiele and the Norwegian Edvard Munch whose ‘Scream’

paintings are perhaps the sine qua non of the Expressionist style.

See also German expressionism."

Buchanan, Ian. "Expressionism." A

Dictionary of Critical Theory. Oxford University Press,

2010. Oxford Reference. 2010. Web. 23 Jan. 2016

Very

good longer essay on the subject.

Naturalism?

A literary movement prevalent in later nineteenth century America that, as Lars Ahnebrink writes, "a manner and method of composition by which the author portrays life as it is in accordance with the philosophic theory of determinism [. . . .] To a naturalist man can be explained in terms of the forces, usually heredity and environment, which operate upon him" (vi). Ahnebrink writes that naturalist writers exhibit a "post-Darwinian belief that man was fundamentally an animal; his actions therefore depended essentially upon physiological phenomena" (214).

For additional information, see the "Naturalism" paragraph entry in the Oxford Companion to American Literature. For a richer discussion, see the Naturalism and Realism essay from The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature.

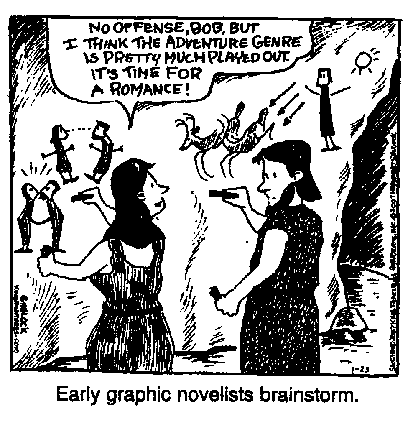

In class work

Day 1 Focus: Art as reflection of culture; filling in the gaps;

style's connection to content; Form

- How is the time period and place the Nuckel wrote in reflected in his work? Think of this from the culture, science, politics and art of Germany in the 1920s

- What does the work gain from being wordless? What does it lose?

- Why titled Destiny?

- Often described as a portrait of urban life: is this true?

- A common theme is a contrast between city and rural life -- between nature and civilization. Do you see such a contrast here?

- What are some of the problems that beset the main character? Why make her a woman?

- Chapter 1 -- what do you make of the opening image? What does the second image convey about the person? Image 4 -- why is the arm out? Image 5 -- first view of father. How much time lapses in this first chapter?

- Chapter 2 -- note the shadows.

- Chapter 3: change in room? Explain.

- What's the significance of the goat in chapter 4 Service?

- Eros and Thanatos: how do they play out in the narrative?

- Why end with the bird? How does it connect to the woman?

- what questions about people and society does the novel raise? How? Marriage?

- Why a carnival in chapter 15. Why titled a crime. What's so bad about a carnival? . The Russian Critic Mikal Bakhtin has argued that "During carnival time life is subject only to its laws, that is, the laws of its own freedom" (7). How does this inform this scene?

- What connections do you see to McCloud?

- Is it fate? Destiny? What other factors are involved?

- Violence in the the story.

- Is there movement in this novel? How is action conveyed in static images?

The System

1997

Back to top

Words/artists to know

Oligarchy; Keith Haring;

- Okay, Destiny was German expressionism, what informs the style here?

- Examine the cover: mechanistic imagery

- Themes: what themes (ideas, problems, etc.) do you see Kuper working with in this novel.

- Why subways? How do they work throughout the novel?

- Connections between Destiny and The System -- world view, style, theme,

- Examine epigraph before chapter 1 Blake: explain

- Pay close attention to the transitions between and on the pages: how does Kruger move readers from page to page? 24

- How does Kruger incorporate sound in this text? 11-12; 13; 28; 53-56; 59-60;

- How does he use panels to convey emotions -- for instance, violence? 45;

- Cosmic: 65;

- Eyes? How does he use them in the novel? Why?

- Mouths: How does he use them in the novel? Why?

- Role of greed? Corporatization? Why have the corporate execs in a strip club? When does this appear in the novel?

- Kid on bottom of 63 and earlier; 96; one supposedly a punk borderline criminal, the other a person preaching morality

- 62-63 money changes hands: both people are killed

- What's the cow on page 65? Page 79-81.

- 64 why the universe panels? Where do they come from? How are they resolved? See Darwin lines on 72 or so

- 67 why the mirror imagery? Why the poster? Arm and money connecting to next page. Cf 32

- 85 use of effect from my favorite genre

- 91 92 cuffs on to cuffs off

All hail the panel!

- 24 great mix of panel sizes

- 45 panels

- 53 panel sizes and shapes. Why?

- 78-80 beautiful succession of panels on death and resurrection

"I thought this was a wordless novel? . . ."

- Epigraph before each chapter?

- 70 how does the word comment on the actions/character on the page?

- 75 bible verse Isaiah 57:3-12 "The Lord here calls apostates and hypocrites to appear before him. When reproved for their sins, and threatened with judgments, they ridiculed the word of God. [ . . . . ]The service of sin is disgraceful slavery; those who thus debase themselves to hell, will justly have their portion there. Men incline to a religion that inflames their unholy passions. They are led to do any evil, however great or vile, if they think it will atone for crimes, or purchase indulgence for some favorite lust. This explains idolatry, whether pagan, Jewish, or antichristian. But those who set up anything instead of God, for their hope and confidence, never will come to a right end. Those who forsake the only right way, wander in a thousand by-paths. The pleasures of sin soon tire, but never satisfy. Those who care not for the word of God and his providences, show they have no fear of God. Sin profits not; it ruins and destroys." From Matthew Henry's Concise Commentary: http://biblehub.com/isaiah/57-11.htm

- 76 newspaper on Muir. Connection to today? What's the name of the newspaper?

- 90 Advertisement for looto connected with drugs

- 101 newspaper account in cab

Comics as history

- 44-45 historical reference. Have students look up Howard beach

- 58 have students look up Boesky.

Back to top

Maus

1: My Father Bleeds History

1980-91 Raw; 1986 Maus I;

1991 Maus II

Back to top

1972 three page

Maus

Interview with Spiegelman on Maus

"Maus is not the only book about World War II experience to employ talking animals to represent the nationalities invovled. The Beast is Dead, a French graphic novel by Calvo and Cancette, presents the Germans as wolves, the French as squirrels and rabbits, the Russians as polar bears, the English as bulldogs, the Americasn as buffalo, the Dutch as cattle, and so forth. The Jews (I am told) appear in only one panel – as rabbits" (Harvey 243)

Day 1: Characters; Form

and construction; P.O.V.; time; connection between word and

images.

- Different Mauses –

- Original comic

- Prologue

- List the characters: what are their . . . um . . . characteristics?

- First panel – show different version – note how faces change and how text changes.

- Shapes: circles

- Repetition for cohesion – rhyming panels

- Why "Bleeds History"?

See pages 12-13

How does it differ from reading a prose work of fiction?

Pages to develop/discuss

- Masks: 66, 138

- Page layout: 111: death of Richieu 113 (basement hideout); 159 gates of Auswitch

- Murderer: 160/161

- Money:116; 129,

- shapes/images: swastika: 127, 129 (repetition of coffin)

- stereotypes/metafiction: 133; 118 wire; 149 (rats/mice)

- Prisoner on the Hell Planet: 101+

- Themetic connections: 120 heart attack

Let's figure out the characters

Textual fidelity/his voice page 29 "Anja was involved in

conspirations!"

Neurotic: page 54 – interrupts to make Art clean the carpet.

"Roh-hanold" 62 – can see the future

Greedy

Plotting/planning : page 17 – won’t marry Lucia b/c she’s poor;

Anja’s pills 21; 65 saved chocolate; 79 "Of course I only said I

got half what I really made. Otherwise they wouldn’t save

anything"

- Chauvinistic

- Critical – 11

- Good liar 104 – keeps tight lips about burning diaries

- Stubborn: his way or the highway 134

- Proud: 60/69, 13

- Controlling: 60/69

Art

- Like father like son – page 25 – promises to not include story about Lucia – but does.

Francious

Anja

Day 2

Content: themes; relationships; history; meta

Fathers and sons: explain their relationship

Prisoner from Planet Hell.

Why have Art in prison stripes?

What style is this? Why?

Chapter titles

- Honeymoon chapter title page: 27. Break down. Why ruffled flag? What do you note about the jews at the pottom? Juxtaposition of title and image?

- 53 – Why give that Nazi solider a tail?

- Circles: 68

- Frame within a frame: 76

Day 3

How is this work a meditation on memory?

On guilt?

Wrapping it up: your own thoughts?

Why did this win a special Pultizer?

Back to top

Maus

2: Here My Troubles Began

Back to top

Day 1

Metafiction, life in the camp, relationship between Art and Vladek

|

Metafiction

Petitjean, Jr., Thomas D. "Metafiction." Identities & Issues in Literature, September 1997, pp. 1-2. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lfh&AN=103331INI17720170000349&site=lrc-live

Buchanan, Ian. "metafiction." A Dictionary of Critical Theory, Oxford Reference, 2010, accessed on 9 Mar. 2017, www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199532919.001.0001/acref-9780199532919-e-439. |

Metafiction

- Opening

- Time Flies

- 205 - Beckett

Relationship between Art and Vladek

- 205-206

Pages to develop/discuss

- Masks: 201-02

- Why the black silhouette? 187, 189, 260

- Metafiction: 205 - Beckett

- Interior state of mind: 206-207

- Favors and "friends" 216, 223, 226

- Resourceful: 220

- Valdek's "stinginess" 233, 250

- Predjudice: 259

- Framing a chapter/page: windows 174-76; 234 gas and flies; beyond the panels 276 ; circle 296

- Ripple effect 239

- Last lines: 296

Watchmen

1986-87

Back to top

Day 1 | Day 2 | Day

3 | Day 4

Historical background

Written in 1986 and set in the near future, the book takes for

granted a close familiarity with the Cold War, Watergate, the Doomsday

Clock, New

York City in decline, and a general sense of malaise.

Follow the links to get this familiarity.

An infamous quote from the Vietnam war picks up on some of the themes in the novel: "We had to destroy the village in order to save it." This is a corruption of a quote from an unnamed American officer. In the original article, Peter Arnett wrote "'It became necessary to destroy the town to save it,' a United States major said today. He was talking about the decision by allied commanders to bomb and shell the town regardless of civilian casualties, to rout the Vietcong." I think you can see the connection here.

Alan Moore from a 2000 interview on Watchmen: "I mean, it's tailor-made for a university class, because there are so many levels and little background details and clever little connections and references in it that it's one that academics can pick over for years" (Kavanagh and Moore).

Postmodernism

Published serially in the 80s.

Quick Summary: alternative history

Superheroes

How does the book differ from the earlier books we've read?

Comics

Code 1954; Comics

Code 1971; Comics

Code 1989

Prepare to choose a page and talk it out

|

Postmodernism A disputed term that occupied much late 20th-century debate about culture from the early 1980s. In its simplest and least satisfactory sense it refers generally to the phase of 20th-century Western culture that succeeded the reign of high modernism, thus indicating the products of the age of mass television since the mid-1950s. More often, though, it is applied to a cultural condition prevailing in the advanced capitalist societies since the 1960s, characterized by a superabundance of disconnected images and styles—most noticeably in television, advertising, commercial design, and pop video. In this sense, promoted by Jean Baudrillard and other commentators, postmodernity is said to be a culture of fragmentary sensations, eclectic nostalgia, disposable simulacra, and promiscuous superficiality, in which the traditionally valued qualities of depth, coherence, meaning, originality, and authenticity are evacuated or dissolved amid the random swirl of empty signals. As applied to literature and other arts, the term is notoriously ambiguous, implying either that modernism has been superseded or that it has continued into a new phase. Postmodernism may be seen as a continuation of modernism’s alienated mood and disorienting techniques and at the same time as an abandonment of its determined quest for artistic coherence in a fragmented world: in very crude terms, where a modernist artist or writer would try to wrest a meaning from the world through myth, symbol, or formal complexity, the postmodernist greets the absurd or meaningless confusion of contemporary existence with a certain numbed or flippant indifference, favouring self-consciously ‘depthless’ works of fabulation, pastiche, bricolage, or aleatory disconnection. The term cannot usefully serve as an inclusive description of all literature since the 1950s or 1960s, but is applied selectively to those works that display most evidently the moods and formal disconnections described above. In poetry, it has been applied most often to the work of the New York school and to Language poetry; in drama mainly to the ‘absurdist’ tradition; but is used more widely in reference to fiction, notably to the novels (or anti-novels) and stories of Thomas Pynchon, Kurt Vonnegut, Italo Calvino, Vladimir Nabokov, William S. Burroughs, Angela Carter, Salman Rushdie, Peter Ackroyd, Julian Barnes, Jeanette Winterson, and many of their followers. Some of their works, like Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973) and Nabokov’s Ada (1969), employ devices reminiscent of science fiction, playing with contradictory orders of reality or the irruption of the fabulous into the secular world. Opinion is still divided, however, on the value of the term and of the phenomenon it purports to describe. Those who most often use it tend to welcome ‘the postmodern’ as a liberation from the hierarchy of ‘high’ and ‘low’ cultures; while sceptics regard the term as a symptom of irresponsible academic euphoria about the glitter of consumerist capitalism and its moral vacuity. See also post-structuralism. Baldick, Chris. "postmodernism." The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms, Oxford University Press, 2015. Oxford Reference, accessed 28 Mar. 2019 |

Focus for Today: Semiotics - Nixon; continued work on characters

"Fearful Symmetry"

Read "Tyger, Tyger" . . . : "there be tygers"

| Deism A generic term for the "rational" religion that challenged orthodox Christianity from the middle Colonial Era through the era of the Early Republic. Essentially an Enlightenment phenomenon, American deism was inspired by British free thought; Newtonian physics; the empiricist psychology of John Locke; and, in the later eighteenth century, French revolutionary thought. American thinkers in the early eighteenth century were moderately influenced by deism, but by the 1780s it had become popular and militant. Both Ethan Allen (1738–1789) in Reason the Only Oracle of Man (1784) and Thomas Paine in The Age of Reason (1794) publicly and notoriously endorsed it. Deism reached its high point in the 1790s under the radical leadership of Elihu Palmer (1764–1806). A number of deistical societies, "temples of reason," and newspapers devoted to rational religion were launched. Deists rejected Christian belief in scriptural inerrancy, miracles, Jesus's divinity, and revelation. Some also condemned Christianity on moral grounds, arguing that it encouraged intolerance, superstition, and irrationality. As an alternative, deism posited an impersonal First Cause whose rationality is reflected in physical laws and human intellect and lauded the exercise of virtue and reason as the truest form of worship. As notorious for their radical republicanism as for their religious heterodoxy, deists defended free speech and universal tolerance, opposed slavery and the conservative principles of the Federalist Party, and enthusiastically endorsed the radical ideology of the French Revolution. Thomas Jefferson, a deist sympathizer, was vilified during his first presidential campaign in 1800 as a libertine infidel. Rational religion and radical republicanism remained associated in the public mind throughout the next few decades. Deism waned as the Enlightenment gave way to the Romantic movement and a resurgent Christian evangelism in the early nineteenth century. But its ideal of rational religion inspired liberal versions of Christianity such as unitarianism and universalism. Moreover, its advocacy of religious freedom and separation of church and state helped enshrine these two principles in the American mind. Walters, Kerry S. "Deism." The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Cultural and Intellectual History. https://www-oxfordreference-com.libproxy.ocean.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199764358.001.0001/acref-9780199764358-e-183, Oxford Reference, 2013, accessed 18 Mar. 2024. |

| Watchmaker Analogy The watchmaker analogy or watchmaker argument is a teleological argument originating in natural theology, which is often used to argue for the pseudoscientific concept of intelligent design. The analogy states that a design implies a designer, by an intelligent designer, i.e. a creator deity. The watchmaker analogy was given by William Paley in his 1802 book Natural Theology or Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity.[1] The original analogy played a prominent role in natural theology and the "argument from design," where it was used to support arguments for the existence of God of the universe, in both Christianity and Deism. Prior to Paley, however, Sir Isaac Newton, René Descartes, and others from the time of the scientific revolution had each believed "that the physical laws he [each] had uncovered revealed the mechanical perfection of the workings of the universe to be akin to a watch, wherein the watchmaker is God."[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Watchmaker_analogy |

Synopsis of the book from Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Watchmen)

SynopsisSettingWatchmen is set in an alternate reality that closely mirrors the contemporary world of the 1980s. The primary difference is the presence of superheroes. The point of divergence occurs in the year 1938. Their existence in this version of the United States is shown to have dramatically affected and altered the outcomes of real-world events such as the Vietnam War and the presidency of Richard Nixon.[31] In keeping with the realism of the series, although the costumed crimefighters of Watchmen are commonly called "superheroes", only one, named Doctor Manhattan, possesses any superhuman abilities.[32] The war in Vietnam ends with an American victory in 1971 and Nixon is still president as of October 1985 upon the Watergate scandal not coming to pass. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan occurs approximately six years later than in real life. When the story begins, the existence of Doctor Manhattan has given the U.S. a strategic advantage over the Soviet Union, which has dramatically increased Cold War tensions. Eventually, by 1977, superheroes grow unpopular among the police and the public, leading them to be outlawed with the passage of the Keene Act. While many of the heroes retired, Doctor Manhattan and another superhero, known as The Comedian, operate as government-sanctioned agents. Another named Rorschach continues to operate outside the law.[33] PlotIn October 1985, New York City detectives are investigating the murder of Edward Blake. With the police having no leads, costumed vigilante Rorschach decides to probe further. Discovering Blake to have been the true identity of The Comedian, a costumed hero employed by the U.S. government, Rorschach believes he has discovered a plot to terminate costumed adventurers and sets about warning four of his retired comrades: Dan Dreiberg (formerly the second Nite Owl), the superpowered and emotionally detached Jon Osterman (codenamed Doctor Manhattan) and his lover Laurie Juspeczyk (the second Silk Spectre), and Adrian Veidt (once the hero Ozymandias, and now a successful businessman). After Blake's funeral, Manhattan is accused on national television of being the cause of cancer in friends and former colleagues. When the government takes the accusations seriously, Manhattan exiles himself to Mars. As the U.S. depends on Manhattan as a strategic military asset, his departure throws humanity into political turmoil, with the Soviets invading Afghanistan to capitalize on the perceived American weakness. Rorschach's concerns appear vindicated when Veidt narrowly survives an assassination attempt and Rorschach himself is framed and imprisoned for murdering a former supervillain named Moloch. Neglected in her relationship with the once-human Manhattan, whose now-godlike powers and transformation have removed him completely from the everyday concerns of living beings, and no longer kept on retainer by the government, Juspeczyk stays with Dreiberg. They begin a romance, don their costumes, and resume vigilante work as they grow closer together. With Dreiberg starting to believe some aspects of Rorschach's conspiracy theory, the pair takes it upon themselves to break him out of prison. After looking back on his own personal history, Manhattan places the fate of his involvement with human affairs in Juspeczyk's hands. He teleports her to Mars to make the case for emotional investment. During the course of the argument, Juspeczyk is forced to come to terms with the fact that Blake, who once attempted to rape her mother, was, in fact, her biological father following a second, consensual relationship. This discovery, reflecting the complexity of human emotions and relationships, re-sparks Manhattan's interest in humanity. On Earth, Nite Owl and Rorschach continue to uncover the conspiracy and find evidence that Veidt may be behind the plan. Rorschach writes his suspicions about Veidt in his journal, in which he has been recording his entire investigation, and mails it to New Frontiersman, a local right-wing newspaper. The pair then confront Veidt at his Antarctic retreat. Veidt explains his underlying plan is to save humanity from impending nuclear war by faking an alien invasion in New York, which will annihilate half the city's population. He hopes this will unite the superpowers against a perceived common enemy. He also reveals that he had murdered The Comedian, arranged for Manhattan's past associates to contract cancer, staged the attempt on his own life in order to place himself above suspicion, and killed Moloch in order to frame Rorschach. This was all done in an attempt to prevent his plan from being exposed. Nite Owl and Rorschach find Veidt's logic callous and abhorrent, but Veidt has already enacted his plan. When Manhattan and Juspeczyk arrive back on Earth, they are confronted by mass destruction and death in New York, with a gigantic squid-like creature, created by Veidt's laboratories, dead in the middle of the city. Manhattan notices his prescient abilities are limited by tachyons emanating from the Antarctic and the pair teleport there. They discover Veidt's involvement and confront him. Veidt shows everyone news broadcasts confirming that the emergence of a new threat has indeed prompted peaceful co-operation between the superpowers; this leads almost all present to agree that concealing the truth is in the best interests of world peace. Rorschach refuses to compromise and leaves, intent on revealing the truth. As he is making his way back, he is confronted by Manhattan. Rorschach declares that Manhattan will have to kill him to stop him from exposing Veidt, which Manhattan duly does. Manhattan then wanders through the base and finds Veidt, who asks him if he did the right thing in the end. Manhattan responds that "nothing ever ends" before leaving the Earth to create life elsewhere. Dreiberg and Juspeczyk go into hiding under new identities and continue their romance. Back in New York, the editor at New Frontiersman asks his assistant to find some filler material from the "crank file", a collection of rejected submissions to the paper, many of which have not been reviewed yet. The series ends with the young man reaching toward the pile of discarded submissions, near the top of which is Rorschach's journal. From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Watchmen |

How a literary term can perfectly capture a literary work.

|

noir A term derived from French critical usage, both literary and cinematic, and applied in English to a kind of crime novel or thriller characterized less by rational investigation (as in the classic detective story) than by violence, treachery, and moral confusion. In French usage, film noir is a period style of 1940s and 1950s American movie thriller commonly adapted from hard-boiled detective fiction (as in the film versions of The Big Sleep, The Maltese Falcon, and others) and distinguished cinematically by the use of menacing shadows and camera angles, while the roman noir (a term once applied to Gothic novels) is broadly equivalent to the thriller. Although noir fiction derives in important ways from the hard-boiled school of detective writing and overlaps with it at some points (especially in the case of James M. Cain’s work), it can be distinguished from most detective stories and from other kinds of thriller by its powerful tendency to dissolve orderly distinctions between the roles of criminal and hero: thus in Cain’s Double Indemnity (1936) and The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934), the protagonists are lured into murder by sexual obsession. In noir fiction generally, rational detachment is overwhelmed by criminal temptation and bewildered by multiple deceptions, and the reader is commonly invited to adopt the point of view of a murderer or of an accessory to serious crime. Leading practitioners include Jim Thompson (e.g. The Killer Inside Me, 1952), Patricia Highsmith (in The Talented Mr Ripley, 1955, and its sequels), and James Ellroy (e.g. The Black Dahlia, 1987). Baldick, Chris. "noir." The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms, Oxford University Press, 2015, Oxford Reference, accessed 8 May. 2019 |

April 11, 2016, turning into a Leisure Village.

Chapter 4

What does a photograph do to time?

Day 3

Search and read Ozymandias by Shelly. How is the poem like Viedt? Then go to end of Chapter XI where Viedt explains what happens -- then last panel/page>and then back to first pages of chapter (location 347).

- What do you make of the documents in the novel? What purpose do they serve? How do they complement the narrative?

"Ozymandias" by Shelley

| Kitty Genovese Murder One night in 1964, a woman was stabbed and murdered in New York City. Kitty Genovese had parked her car in a Long Island Railroad lot, in a building adjacent to her residence. Waiting for her in a car nearby was a man named William Moseley. Hidden in the shadows, he had watched her as she parked. When Genovese spotted him and ran, Moseley chased her and stabbed her in the back. A neighbor yelled from a window, and Moseley temporarily moved away. Meanwhile, Genovese got up and tried to get inside the building, but Moseley found her and stabbed her again. He then raped her and stole some of her belongings. An apartment door opened and some voices were heard, but no one interfered. Moseley left Genovese and even exchanged glances with a milkman before going into his car and driving off. One of the neighbors called the police, but Genovese had already died before she could be brought to the hospital. Moseley committed more crimes and was caught while holding a mother and daughter hostage in their house. The FBI was contacted and apprehended Moseley later on. He was sentenced to life in Great Meadow Correctional Facility in upstate New York. The Kitty Genovese murder was appalling due to the inaction of many witnesses. Over 30 people were reported to have witnessed Genovese's murder. It left the impression in the public that people were starting to become apathetic and uncaring, perhaps due to the changing attitudes in society and the growing isolation of a person in a big city. It implied that people no longer cared if a crime was being committed on their doorstep, just as long as it was another person suffering. It also implied that if you lived in a big city, there was a greater chance of being a crime victim without anyone coming to help. It gave the name to the Genovese Syndrome or Bystander Effect, the phenomenon of witnesses failing to report when a crime is committed. Fernandez, Chino. “Crime and Violence in Postwar America.” Crime and Violence in Postwar America, Facts On File, 2016, accessed 24 March 2024. |

"The Abyss Gazes Also"

|

From "Nietzsche" Nietzsche is unchallenged as the most insightful and powerful critic of the moral climate of the 19th century. His exploration of unconscious motivations anticipated Freud. He is notorious for stressing the ‘will to power’ that is the basis of human nature, the ‘resentment’ that comes when it is denied its basis in action, and the corruptions of human nature encouraged by religions, such as Christianity, that feed on such resentment. But the powerful human being who escapes all this, the ‘Übermensch’, is not the ‘blond beast’ of later fascism; it is a human being who has mastered passion, risen above the senseless flux, and given creative style to his or her character. Nietzsche’s free spirits recognize themselves by their joyful attitude to eternal return. He frequently presents the creative artist rather than the warlord as his best exemplar of the type, but the disquieting fact remains that he seems to leave himself no words to condemn any uncaged beasts of prey who best find their style by exerting repulsive power over others. This problem is not helped by Nietzsche’s frequently expressed misogyny, although in such matters the interpretation of his many-layered and ironic writings is not always straightforward. Similarly, such anti-Semitism as has been found in his work is balanced by an equally vehement denunciation of anti-Semitism, and an equal or greater dislike of the German character of his time. Nietzsche’s current influence derives not only from his celebration of the will, but more deeply from his scepticism about the notions of truth and fact. In particular, he anticipated many of the central tenets of postmodernism: an aesthetic attitude towards the world that sees it as a ‘text’; the denial of facts; the denial of essences; the celebration of the plurality of interpretations and of the fragmented self; as well as the downgrading of reason and the politicization of discourse. All awaited rediscovery in the late 20th century. Nietzsche also has the incomparable advantage over his followers of being a wonderful stylist, and his perspectivism is echoed in the shifting array of literary devices—humour, irony, exaggeration, aphorisms, verse, dialogue, parody—with which he explores human life and history. Blackburn, Simon. "Nietzsche, Friedrich." The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy, Oxford University Press, January 2016, Oxford Online Reference, accessed 11 Apr. 2019 |

|

Übermensch The ideal superior man of the future who could rise above conventional Christian morality to create and impose his own values, originally described by Nietzsche in Thus Spake Zarathustra (1883–5). Nietzsche thought that such a being could arise when any man of superior potential shook off the conventional Christian morality of the masses to create and impose his own values. "Übermensch." The Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, Oxford University Press, 2006. Oxford Reference, accessed 11 April 2019. |

|

Existentialism Sartrean [from Jean-Paul Satre] existentialism, as distinct from the Christian existentialism derived from [Soren] Kierkegaard, is an atheist philosophy of human freedom conceived in terms of individual responsibility and authenticity. Its fundamental premiss that ‘existence precedes essence’, implies that we as human beings have no given essence or nature but must forge our own values and meanings in an inherently meaningless or absurd world of existence. Obliged to make our own choices, we can either confront the anguish (or Angst) of this responsibility, or evade it by claiming obedience to some determining convention or duty, thus acting in ‘bad faith’. Paradoxically, we are ‘condemned to be free’. Similar themes can be found in the novels and essays of Camus; both authors felt that the absurdity of existence could be redeemed through the individual's decision to become engagé (‘committed’) within social and political causes opposing fascism and imperialism. Some of the concerns of French existentialism are echoed in English in Thom Gunn's early collection of poems. The Sense of Movement (1957), and in the fiction of Iris Murdoch and John Fowles. See also phenomenology. For an introductory anthology, consult Paul S. Macdonald (ed.), The Existentialist Reader (2001). "existentialism" The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms, edited by Chris Baldick, Oxford University Press, 2008, Oxford Reference Online, Oxford University Press, accessed 28 February 2009. |

Day 4

- Intertextuality: texts within the text -- why? What's the effect on the reader?

Themes: what is Moore and Gibbons "saying" about America?

Generate a list then find how this is true.

Compendium of Watchmen Questions/Notes

- 31 nixion poster right after R’s inflexible notions of right and wrong

- 8 and 33 rhyming panels to end chapter

- News vendor, as stand in for everyman with their mass of contradictions. His first line: “we order nuke Russia and let God sort it out“ (77) his philosophy is that “in the end, a man stands alone” open, parentheses, 94, and then just a few pages later, after he finds out about Russia, invading Afghanistan, “we all got a look out for each other. Don’t we? I mean that’s my philosophy“ (101

- 102: the banality of evil “… There we are. Britain down, Germany down… Well, I’ve seen worse scenarios“ 102 whenever Kissinger appears, not that good. 1

- 104: Manhattan as God 106 and throughout: new frontiersmen as crank news site. Newsmax, Fox News, one America, etc. 95 “it seems I’m in capable of cohabiting safely either emotionally or physically“ doc. Manhattan 97 Manhattan as God: “had he been there once, but now departed?” 99: Manhattan, as “the linchpin of America, strategic superiority“ and he’s “gone to Mars!“

- 107. Hollis from under the hood. The usual conservative fear about the youth. The uneasiness about Doc Manhattan, picking up on the uneasiness of the existential dread of nuclear annihilation.

- 111:Dr. Manhattan been in two places at the same time.

- 113, “Professor Einstein says that time differs from place to place. Can you imagine” “it is 1948” “it is 1958 112 “I am trying to give a name to the force that set them in motion” followed by “watchmaker” Need to define deism and put it on the course site

- 115 “ My dad sort of pushed me into it. That happens a lot. Other people seem to make all my moves for me.” Dr. Manhattan.

- 121 “they say you’re like god now” “I don’t think there is a god” 126 “ I can’t prevent the future. To me, it’s already happening“ 127 what does Dr manhattans kiss of Laurie demonstrate about him. (He’s human) 135 “I’m tired of this world” 138 Einstein “if only I had known, I shouyhave become a watch maker”

- 140 “Furthermore, as ever-escalating amounts of money are poured into the pursuit of the specific weapon or conflict that will bring lasting peace, the drain on our economies creates a rundown urban landscape where crime flourishes and people are concerned less with national security than with the simple personal security needed to stop at the store late at night for a quart of milk without being mugged. The places we struggled so viciously to keep safe are becoming increasingly dangerous. The wars to end wars, the weapons to end wars, these things have failed us.” Military industrial complex

- 123 “Superman exists and he’s American” 124”side-our leaders have become intoxicated with a heady draught of Omnipotence-by-Association, without realizing just how his very existence has deformed the lives of every living creature on the face of this planet. This is true in a domestic sense as well as a broader, international one. The technology that Dr. Manhattan has made possible has changed the way we think about our clothes, our food, our travel. We drive in electric cars and travel in leisure and comfort in clean, economical airships. Our entire culture has had to contort itself to accommodate the presence of something more than human, and we have all felt the results of this. The evidence surrounds us, in our everyday lives and on the front pages of the newspapers we read. One single being has been allowed to change the entire world, pushing it closer to its eventual destruction in the process. The Gods now walk amongst us, affecting the lives of every man, woman and child on the planet in a direct way rather than through mythology and the reassurances of faith. The safety of a whole world rests in the hands of a being far beyond what we understand to be human. We are all of us living in the shadow of Manhattan.” what does this mean, particularly that last line – why Dr. Manhattan instead of Dr. Gila Flats? What’s the connotation of Manhattan?

- 155 “without removing the skin from my head“ Rorschach can’t separate his alias from himself

- 161 foreshadowing. “You never know what’s bearing down on you” says the news vendor. In the background “institute of extraspatial studies” inscribed on building.

- 172 rorshach “ my face! Give it back!“

- 176 Max Shea. Script writer for “marooned” Who goes missing. Is part of Ozymandias‘s plot.

- 179 Dr. Malcom Long 1985 from his report on shack test with Walter/Roche: “he never seems to blink“ and follow this with an example of hubris: “no problem is beyond the grasp of a good, psycho analyst, and they tell me I’m very good with people“ he alsois fooled by Walter answers: “surprisingly bright and positive and healthy”

- 181: repetitious images. Silhouette of lovers kissing.

- 184: walter attacks bullies - old (hardened) v young face (innocent)

- 188: kitty Genovese Add note to web site Title is from desolation row Pg 26, 27,28 for dual meaning panel - see mccloud

- 143 rum runner bar lights Location 318 Chap X page 5 - to first panel with R in window location

- 321/322 both video and Dan using data and screens. V on a grand scale

- 330 reference to brain before ship blows up.

- 335 R initials in journal like Jolly Roger bar 143

- 349 Veidt Tells his big cat “I hope they know when to stop” but one of them does not know when to stop:note that Dan is putting his hand up to hold their progress; he’s trying to hold roarschak

Back to top

Ghost World

1993-1997

Back to top

Simpsons digging on alternative comics -- and I think you'll recognize everyone.

Words to know

Ennui, anomie, angst

| Oh

. . . to be 18 AVC: A lot of your protagonists are between 18 and 21. What about that age interests you? DC: I see a lot of possibilities in that age. You have a window of opportunity when you leave your childhood behind and have this chance to become what you always wanted to be. For me, that was a time when I could have gone many different ways. I was in flux and deciding what kind of person I would become. There's something interesting about the vision of what that will be and the reality of making that happen, and how you really are what you are. Unless you're "in character," it's impossible to get around that. I can see it in my son. He's 3 years old and has such a clear personality. I don't think it has anything to do with our influence. All we can do is inflect it somehow, but he already is his own person. I always tried to interpret my childhood, to find what events turned me into the person I am today. Now I see that probably none of them did. I probably would have gone in the same route, personality-wise, no matter what. https://www.avclub.com/daniel-clowes-1798213044 |

| Enid,

you drive me crazy I have a very low tolerance for the falsely likable characters of most movies and fiction. Like villains, disagreeable characters give you so much more than the amiable ciphers one is usually asked to identify with, but I think it’s essential, over the course of each story, for the author (i.e. me) to find a way to fully embrace and understand his protagonist’s humanity and, in the final reckoning, to find a way to love and forgive his misguided monster. https://lit.newcity.com/2011/10/12/out-of-this-world-dan-clowes-and-seth-find-common-ground-in-uncommon-places/ |

| Awk-ward

. . . I find awkwardness to be dramatically interesting, I guess . . . . I've often had experiences just making a doctor's appointment on the phone and it has this great dramatic import for me, so that's something I've always gravitated towards as good material. I know a lot of people who don't respond to that in their daily lives and fit it just odd that anyone would have found these little awkward moments interesting." "Daniel Clowes On . . . " The Daniel Clowes Reader |

Setting and Character

- How does Clowes supply back story?

- Just what is Ghost World?

- What’s the role of television in this novel?

- How is this different than other novels we’ve read?

- How is it similar?

- What is the "Ghost World"? The world in which they live. Note the color – it’s not black/white, it’s black, white and odd green which casts a ghostly shadow on the characters

- Who is painting the graffiti?

- Does the novel add up to a point or is it just a random series of events? (coming of age)

- Connections to other novels we’ve read

- Suburban culture

Anomie, ennui, boredom

Disconnected

Middle-class

Ahistorical

Retro (looking back to an imagined past)

Television

Consumer culture

And a reaction to this consumer culture

Zine culture

Acting radical

Irony/detachment (which distances you from anything)

Cool rules

- Why a Diner -- and why so many?

- What is Enid's personality? She’s trying to create a personality.

- What role does television play in the novel? How does it effect the characters?

- What do we know about Enid's past? How does it effect our understanding of her character? Since this is a character study rather than a plot driven novel, the psychology of the characters predominates. It’s not so much what they do but how what they do reveals about their characters.

- Why a hearse?

- Relationship with her father – and with adults in general

- Fantasy world – note that she lives in a fantasy world –

typical teenager, makes up worlds – this gives her an "out"

****page 76 – interesting bit about Rebbeca’s eyes

From Clowes' "Modern Cartoonist"

|

Comics tend to lean toward the iconic ("The Adventures of a Featureless Blob") because it encourages reader identification. Let's get away from the arena of vagueness (a cheap gimmick designed to flatter the shallow reader) [12] and into the realm of the specific. Study and contemplate the nature of pictorial stillness. What does the still picture have to offer a narrative that the moving one doesn't. Find and study an intriguing movie still from a film you've never seen, then watch the movie to see how and why it falls apart and loses its compelling mystique. Think of the comic panel (or page or story) as a living mechanism with, for example, the text representing the brain (the internal; ideas, religion) and the pictures representing the body (the external; biology, etc.), brought to life by the almost tangible spark created by the perfect juxtaposition of panels in sequence. Consider using all of the "hokey" devices available in comics vocabulary (thought balloons, sound effects, etc.). They are no less inherently neutral than a comma or a whisper of a lap dissolve and it is only their debased usage that has made them so. The comic book really is a perfect consumer item. It's portable, flexible, cheap enough to be disposable, durable enough to last several lifetimes with proper archival care, lightweight, colorful and simple (no packaging or shrink -wrap required). Think in terms of the entire package, the structural cohesion of every component (from page numbers to indicia, etc.). (11-12) |

Clowes, Daniel. The Daniel Clowes Reader. Edited by Ken Parille, Fantagraphic Books, 2013.

Semiotics: books, other objects. What do they symbolize?

Focus on individual chapters

Nihilism

|

nihilism Buchanan, Ian. "nihilism." A Dictionary of Critical Theory, Oxford University Press, 2018, Oxford Reference, accessed 16 April 2019. nihilism Blackburn, Simon. "nihilism." The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy, Oxford University Press, 2016, Oxford Reference, accessed 16 April 2019. |

Development of theme

"To Girls, Sassy Meant Something More"

Zine culture: page 27

Let’s Get GrotesqueWhen we hear the word "grotesque," we usually substitute the word "gross." However, grotesque has specific literary denotations – as follows: ********************** Anything having the "qualities of grotesque art: bizarre, incongruous, ugly unnatural, fantastic, abnormal" (Harmon and Holman 239-40) "Modern critics use ‘the grotesque’ to refer to special types of writing, to kinds of characters, and to subject matters. The interest in the grotesque is usually considered an outgrowth of interest in the irrational, distrust of any cosmic order, and frustration at humankind’s lot in the universe. In this sense, grotesque is the merging of the comic and tragic, resulting from our loss of faith in the moral universe essential to tragedy and in rational order essential to comedy [. . . .] Thomas Mann sees it as the ‘most genuine style’ for the modern world and the ‘only guise in which the sublime may appear’ now. Jorge Luis Borges echoed Mann’s sentiment. Flannery O’Conner seems to mean the same thing when she calls the grotesque character ‘man forced to meet the extremes of his own nature.’" (Harmon and Holman 240) "Sherwood Anderson subtitled his Winesburg, Ohio "the Book of the Grotesque," and defined a grotesque character as a person who "took one of the [many] truths to himself, called it his truth, and tried to live by it.’ Such a person, Anderson asserted, ‘became a grotesque and the truth he embraced a falsehood’" (Harmon and Holman 240) Harmon, William and C. Hugh Holman. A Handbook to Literature. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1996. |

And now, the question is . . . do you see aspects of the above in Ghost World?

Secondary Sources

Interviews, etc. with Daniel Clowes

http://www.randomhouse.com/pantheon/graphicnovels/maus1.html

great site for Ware, Speigelman, and Clowes, And Sarah Boxer

Back to top

Lint

2010

Terms to know

- Antihero

- La petit mort

- Id, Id, Id (more on Freud next class)

|

The Paris Review treatment: interview with Ware "I found it challenging to convince my teachers that an aspiring cartoonist might also have serious goals, and that I wasn’t drawing comics to follow in Lichtenstein’s footsteps or to say how stupid Americans were but to employ them as a visual language to write about what it feels like to be alive." "In short, I think cartooning gets at, and re-creates on the page, some sixth sense—of space and of being in a body—in a way no other medium can quite so easily, or at least so naturally." INTERVIEWER In your comics, there is a strong connection between memory and physical spaces, buildings in particular. Does this have to do with your own way of remembering, or with comics as a medium, or some combination of the two? WARE I’m vaguely familiar with the idea of "the poetics of space," and I guess it’s something I’ve been indirectly writing and drawing about for years now, but I’m woefully uninformed about any real theories around it. Whenever I come across some article about recent neurological research, like how our brain connections are apparently not just a mass of spaghetti but are organized around X, Y, and Z axes, I feel sort of reassured that maybe I’m on the right track, like maybe we build squared-off spaces to contain our lives partly because our memories need the same sort of filing system, and maybe that’s why the most effective means of remembering something is to place it in an image of a house, or a "memory palace." Or maybe not. "Art Spiegelman has defined comics as the art of turning time back into space, which is the best explanation of the medium I think anyone’s yet come up with. The cartoonist has to remain aware of the page as a composition while focusing on the story created by the strings of individual panels. I think this mirrors the way we experience life—being perceptually aware of our momentary present with some murky recollections of our past and vague anticipations of where we’re headed, and all of it contributing to the shape of what we like to think of as our life. I try to flatten out experience and memory on the page so the reader can see, feel, and sense as much of all of this as possible, but it’s really not much different from composing music or planning a building." "It’s also what the core of comics is—a combination of memory and experience into a simplified visual language. What one thinks of as pictures in comics are really the equivalent of drawn words—words meant to be read, not looked at—which is analogous to the way humans perceive the world. Looking is a part of it, but not all of it. It’s ultimately the limiting effect of language on experience, a ratcheting down of perception by the human mind that begins the moment we learn how to communicate with words and to name things. Sometimes I think it’s why time seems to speed up for adults as we age—because we spend so much of our conscious time remembering rather than simply looking." "The weird "Lint" chapter was inspired both by Portrait of the Artist and by Updike’s story "How Was It, Really?" about a late-middle-aged man who tries to remember his life but only comes up with a handful of details and dissociated moments. I thought frequently of Rabbit Angstrom and of how Updike said that by creating a character who was more or less loathsome, he was able to strangely allow a little more of real life in. Maybe Updike’s wanting to be a cartoonist in his youth and his time on the Harvard Lampoon had something to do with the outside-in-ness of Rabbit’s narrative distance, despite the books’ eventual paradoxical closeness. In the long run I think it’s the writer’s duty to find some reason to love, if not fall in love with, all of his or her characters, no matter how repellent they may be. Updike once described writing as something of a moral exercise or experiment. Writing is not playing, but now that I have a daughter, I see that it involves some of the same impulses. As Lynda Barry might say, you take Barbie’s and Ken’s pants off and see what happens." "I’ve said this a million times now, but a book can be something of a metaphor for the human body—it has a face that can reveal itself or lie, it has a spine, it’s bigger on the inside than it is on the outside. The layering of panels and pages and chapters essentially makes a sculpture in space and in the memory of the reader. I also think there’s a certain poetic harmony between the physicality of a book and the ineffability of what it contains, like our bodies with our child selves buried alive inside, to say nothing of what we think of as consciousness somewhere in there as well." "One of the reasons I stayed interested in comics was their potential for getting at the four-dimensional shape of existence, and a lot of my lame undergraduate stuff—pedantic panel-crossing characters, spinning chairs in space—was a sort of unremarkable, self-conscious fooling around with all that, which has had a lingering taint on how I think of the page, book, et cetera, as a "perpetually existing" sort of shape that only comes alive when read. The best comics make drawings seem to come alive on the page and make the visual connections between moments across pages and even chapters concretely explicit, which is a very different experience from looking at page after page of gray text. Not to carry this too far, but unlike regular reading, which induces blindness in the reader, comics bring together the half-awake "night and day" of seeing and remembering directly on the page. " |

- Lyrics to "Stairway to Heaven"

- Recording of "Stairway to Heaven" go to 6:43

Themes:

Freud: Anal complex; violence/aggression; role of parent; sexuality

|

Freud, Sigmund (1856–1939) [ . . . .] Though the

therapeutic benefits of psychoanalysis are disputed,

psychoanalytic ideas have had a profound and lasting

effect on literature itself, on criticism, and on literary

and cultural theory. In an elegy on Freud, W. H. Auden

observed that his ideas had become a ‘climate of opinion’,

and it is true that many of Freud's concepts, often in

simplified or vulgarized form, have entered educated and

even common discourse—e.g. Oedipus complex, repression,

the death instinct, penis envy, narcissism, ‘Freudian’

slips, phallic symbolism (about which he was sceptical),

and his formulation of mental structure as a division

between ‘Id, the Ego, and the Superego’. Freud's thinking

was deeply influenced by literary sources, and on

occasions he was tempted to write directly on literary

topics. Some of these pieces, such as his essay on ‘The

Uncanny’, have been seminal. [. . . .] |

- Freud's Maps of the Mind

- Why Freud?

- Freud and Beyond

- Freud (quick overview)

- The Unconscious and the I (longer -- and most detailed -- discussion)

Theme: jogging, consumer culture

Terms to know- Muscle car

Jordan to his dad: "Can't you get out of your tiny little life for one second and see -- there'a a whole world out there? For just on second? HUH?"

"I know MY mom MEant for ME to MEet . . . you"

Earlier publications

-

Jordan W. Lint to the Age 27.By: Ware, Chris. Virginia Quarterly Review. Spring2008, Vol. 84 Issue 2, p181-187. 7p. , Database: Academic Search Premier

-

Jordan W. Lint to the Age 35.By: Ware, Chris. Virginia Quarterly Review. Fall2008, Vol. 84 Issue 4, p179-187. 9p. , Database: Academic Search PremierPDF Full Text (2.5MB)

-

Jordan W. Lint to the Age 43.By: Ware, Chris. Virginia Quarterly Review. Spring2009, Vol. 85 Issue 2, p115-123. 9p. , Database: Academic Search PremierPDF Full Text (3MB)

-

Jordan W. Lint to the Age 59.

By: Ware, Chris. Virginia Quarterly Review. Fall2009, Vol. 85 Issue 4, p131-139. 9p. , Database: Academic Search PremierPDF Full Text (2.4MB)