Lesson

Plans

Lesson Plans

Course Documents Links

Home Page

Quick

Links

Library

Links

Citing

Sources

Candide

General Questions | Group Questions | Criticism | Pictures

| Links

Country/Date

Written/Published

French

1759

See page on annotation to start off the semester on solid mental footing.

Introduction

Is our world "the best of all possible worlds?" What are we to make of the question of Evil? Is there a benign being watching over us all? How can we, as the English poet John Milton asked in his earlier Paradise Lost (1667), "justify the ways of God to man"?

These are just some of the questions posed by this novel. Of course since this is a "classic" work of literature, the questions are not explicitly answered; if they were, people would have stopped studying the work long ago. Instead, Voltaire pays us the compliment of merely posing the question and asking readers to make up their own minds.

Before you run away in fear of a text which is supposed to be "good for you," rest assured that the novel is also a first-rate adventure tale and love story, filled with tales of sexual intrigue, scenes of war and destruction, travels to exotic locales -- in short, the only thing keeping it from appearing at the Brick Cinema is . . . actually, I can't think of a reason why it isn't appearing at the movies.

Still, while the novel reads like the action story it is, it was written in response to some of the prevailing philosophical ideas of the time. Thus, while on one level it is the story of Candide's search for his love and his many attendant adventures, at another level it is a satiric attack upon accepted wisdom, a thumb in the eye of convention. Of course, times have changed a bit since the 1700s, and what was accepted wisdom then is ancient history to readers in 21st century American. To fully appreciate the novel, I've included below some background material that should fill in some of the gaps in your knowledge of the period, and help flesh out the references to topical events, people, and beliefs that shape the work. I've tried to keep my comments brief because while understanding the background of a work is critical to understanding how it works, what is most important is the work of art the writer actually created.

The Times

The Headlines

Candide was written, in part,

in response to a natural disaster; an 1755 earthquake in Lisbon,

Portugal which killed fifty thousand people. It's also a response to a

human disaster; the long train of wars fought on European soil

throughout the centuries, and the more recent (for Voltaire), Seven

Years war (mid 18th century) which took place in Canada and America.

Social/Cultural/Science/Philosophy

Math + telescope=The Enlightenment. Okay, it's not that

simple, but the mathematic and astronomical discoveries of Copernicus,

Galileo, and Newton established the primacy of reason over blind faith.

Above all, the Scientific Revolution set the stage for a new

way of looking at the world, and its philosophical underpinning of

rationality led to what historians now call The Enlightenment (roughly

beginning by the mid 1600s).

One specific change that has resonance in Candide is based on John Locke's Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690). He argued that the mind was a tabula rasa -- a blank slate -- upon which experience and the environment wrote and formed a consciousness. This seemingly benign belief had important consequences for religion, and since religion was the guiding force of European civilization, it resulted in cultural changes.

Instead of a belief in pre-destination -- we are all "sinners in the hand of an angry God" and "In Adam's fall we sinned all" -- there grew a belief that perhaps free-will was more important than a supposed list of the dammed and the saved. It also set the tone for an optimistic belief in a more providential view of the world. Writers such Gottfried Wilhem Von Liebniz argued that since everything was created by God, and since God was omniscient and omnipotent, everything in the world was good, even if we didn't necessarily understand it. If evil existed, it was only because humans were limited and didn't see the grand design of God.

But the rational ethos of the Enlightenment aroused a more skeptical view of religion. Many educated people (including several of our founding fathers) moved away from a belief in a vengeful or benevolent God to a belief in an indifferent one. This "religion," known as deism, is famously described by the analogy of a clock: a god wound up our world like a clock, set it down, and wandered away. This mindset posits that there was no "grand design:" there was a beginning, and that was it. This meant that the world was random and chaotic and that the cruelty inflicted upon humans by other humans (or by nature) was just that: cruelty.

This view undercut the authority of the church by shifting the emphasis from God to man. Additionally, the emphasis on rationality weakened the powers of organized religion and meant that the Catholic church, which had held sway over much of Europe for centuries, was now questioned. And thus the supremacy of the pope -- and of the Jesuits, an order both respected for their intellectual pursuits and suspected as being spies for the Vatican -- were weakened.

One last cultural note: The "New World" (i.e. the Americas) -- though it wasn't so new anymore, still held promise as a land untainted by the corruption of Europe, and writers such as Rousseau projected upon it the idea of an Edenic past; a place where the humans existed in a pre-lapsarian (before Adam bit into that fateful apple) state and were therefore termed "noble savages."

Political

In the 1700s kings and queens (and to a lesser extent the pope) still

reigned supreme. Associated with a monarchy is class and its

attendant rules and divisions. A rough pecking order would be

the monarchy as chief rooster, then the aristocracy/nobility, clergy

(though a poor priest never stood a chance), wealthy merchants,

intellectuals/ranking military men, soldiers/ working-class, and

everyone else lesser hens. In Candide,

pay

attention to the class tensions and the way Voltaire exploits them.

But this order was weakening. The speculative attitude of the Enlightenment (if the church could be questioned, what about the supposed divine right of kings?) meant that traditional relationships between monarchy and subjects -- indeed between people -- were examined in a new, more rational light. This "enlightened" attitude, in part, fueled the French Revolution in 1789 (thirty years after Candide was first published).

The Arts

One way of showing displeasure or disagreement with something is to

make fun of it. And one way of making fun of something is by satirizing

it. Satire is, ahem, "the literary art of diminishing or

derogating a subject by making it ridiculous and evoking toward it

attitudes of amusement, contempt, scorn, or indignation" (Abrams 166).

In other words, making fun of something to show you don't

agree with it.

Usually, satire works by using exaggeration or irony to expose the weakness of a subject. In particular, irony -- which in literature can be defined as the difference between what is said or done and what the author wants the audience to understand -- works as satire's hitman. Example of irony? Okay, Jonathan Swift, in his "A Modest Proposal," (1729 -- compare with Candide) offers a novel solution to Irish overpopulation: cannibalism. He makes fun of ideas such as supply and demand by satirically suggesting that the Irish grow children and sell them like so many heads of cattle. While Swift offers his proposal with a rhetorical straight face, the reader understands that Swift is merely exaggerating for effect.

A naive hero makes for a great ironic character. We can look at this person and shake our heads in knowing disbelief as he or she falls again and again for what we can readily see is false. A writer can easily set up such a persona and place him/her in different situations to illustrate the hypocrisies of life.

One final aesthetic (and philosophical) idea you should be familiar with is the concept of Utopia. The idea of an imaginary and perfect realm has long held a grip on our imagination. Plato's Republic (fourth century B.C.) is one of the first examples, but later examples include Sir Thomas More's Utopia (1515-16) and Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726). Of course, as the word suggests (with connotations of the Greek word "outopia" (no place) and "eutopia" (good place), this is an imaginary world. Taken in a religious context, it usually refers to an Edenic, pre-laspesarian locale.

The Life

Voltaire showed his rebellious streak at an early age, rebelling

against his family by living with his godfather, Abbé de Châteauneuf,

a" freethinker and Epicurean" (Penguin). At twenty two, he

was exiled for writing a satire of the Duke of Orleans. At

twenty three, he was imprisoned in the Bastille for eleven months, for

writing yet another satire.

This was only the start of a long career as an essayist, historian, dramatist, and novelist. Throughout all his works, he probes the injustices of man, and delights in exposing our prejudices and hypocrisy. While this could get tiresome, when it is done with wit and verve, as Voltaire does, it is a mental Altoid ("The curiously strong mint"), clearing away the accumulated refuse of cultural static and letting readers discern what is truly just and truly important.

On Candide itself, Voltaire made

some rather interesting responses. . . .

See his entry entitled "All's

Well" in his Philosophical Dictionary;

his letter

to a friend concerning the earthquake in Lisbon; and a letter to the editor

in response to a review of the novel.

Terms

conte The French word for a tale, applied since the 19th century to short stories , but previously used to denote a more fanciful kind of short prose fiction, especially that deriving from oral tradition . Among the kinds of conte are the folktale or conte populaire, the fairy tale (conte merveilleux or conte de fées), and the nursery rhyme or conte rimé. In the more literary manner is the conte philosophique, of which Voltaire's Zadig ( 1747 ) and Candide ( 1759 ) are major examples. A storyteller is a conteur.

"Conte." The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Ed. Chris Baldick. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Web. 27 September 2010

picaresque: A literary genre in sixteenth and seventeenth-century Spain. The picaresque novel was an episodic first-person narrative that related the adventures (often criminal or sexual) of a shrewd rogue (pícaro) of humble origin; in this respect it was an antidote to the romance of chivalry, which celebrated the high ideals of aristocratic heroes.

The prototype of the picaresque novel was the anonymous Lazarillo de Tormes (1554), which was later imitated in England by Thomas Nashe (The Unfortunate Traveller, 1594). The most influential example of the genre is Mateo Alemán's Guzmán de Alfarache (1599–1602), which was imitated in Germany by Johann Grimmelshausen (Simplicissimus, 1669), in France by Alain-René Lesage (Gil Blas de Santillane, 1715–35), and in England by Defoe (Moll Flanders, 1722). In early seventeenth-century Spain, the most important inheritors of Alemán were the pseudonymous author of La pícara Justina (1605), Vicente Espinel (Marcos de Obregón, 1618), Jerónimo Alcalá de Henares Yáñez (Alonso, mozo de muchos amos, 1624–6), and Quevedo, the greatest exponent of the genre (El buscón, 1626).

Bibliography

A. A. Parker, Literature and the Delinquent: The Picaresque

Novel in Spain and Europe, 1599–1753 (1967);

H. Sieber, The Picaresque (1977);

F. Rico, The Spanish Picaresque Novel and Point of View

(1984);

Giancarlo Maiorino (ed.), The Picaresque (1996).

Questions to mull over as you interpret the story

- Is this a "realistic" novel? (careful – depends on your definition of realism).

- What are Candide’s expectations at the end of Chapter 1?

- What could the three gardens represent?

- While Voltaire is relentlessly satirical, there are some positive characters/actions in the text. What are they and from what does this goodness stem? What does this suggest about Voltaire’s view of the world?

- Is it possible to tell which character's views Voltaire endorses? Why or Why not?

- Does human nature change in different parts of the world?

- What does Eldorado symbolize?

- How is Eldorado different from Europe?

- What seems to hold together the society in Eldorado? What do they seem to value above all?

- How does this fit in with Voltaire’s views and his own culture?

- What kind of world does Voltaire suggest is best? What in the story supports this?

- Consider Martin's philosophy of the evil of man (chap 21 and 22). Is this true in the world created in the novel?

- What does Voltaire seem to be against? (Be prepared to make a list and support each item on the list with a specific quote/passage)

- In the final chapter, why doesn’t the farm work at first? Does it work in the end? How can you tell?

- Explain how the final sentence "but we must cultivate our garden" (87) could be Voltaire's answer to the problems of the world

- Dictionary: transports

- Need a question regarding Eldorado and myth: the only place the world is good is there and it’s a mythic place (chap 22 564)

- Rousseau: What’s the irony: “it seems that uncorrupted nature is good, since these folk, instead of eating me, showed me a thousand kindnesses as soon as they knew I was not a Jesuit” (end of chap 16). Rousseau Discourse on the Origin and Basic Inequality Among Men (1754)

- Candide “At least we may find something new” beginning of chap 17; cf Cacambo 541

- Key theme: Chap 18 Candide: “to know the world one must travel” (549)

- Eldorado

- Why is Candide most impressed by the “palaces of sciences” (chap 18)?

- ***What do you make of Cacambo’s and Candide’s decision to leave Eldorado (chap 18); note what the king says “when you are pretty comfortable somewhere, you had better stay there” (chap 18)

- Small detail: why discuss the behavior of the Eldoradians at the hotel? Chap 17, 547.

- Why the exotic and high numbers in Eldorado? (the dinner chap 17, the King’s castle chap 18,)

- Candide rejects Pangloss’s philosophy: end of chap 17, chap 19,

- Why have the disfigured beggar in chapter 19? “This is the price of the sugar you eat in Europe”

- Chap. 20: how far off is he from today (regarding the state of the world)?

- What’s the role of money in the novel? Does it help or hurt? (cf. Martin “your pastries may make them even more unhappy then they were before” (chap 24) – what makes Eldorado such a pleasant place? [What was the role of money in Stone? In “The Narrow Road”?]

- Why include the Jacques the Anabaptist?

- Why add the character Pococurante (chap 25); does he add to the action of the novel or to the idea or both? Consider, for example, his quote “I read only for my own pleasure; I like only what is in my style” (chap 25) – does Voltaire condone or condemn this idea? How can you tell? Candide “what a great genius this Pococurante must be! Nothing can please him” (chap 25)

- Why the chapter with the dethroned royalty (chap 26)? What message is Voltaire conveying here?

- Why make Cunegonde so ugly (chap 29)?

- Strong anti-semitism (chap 30), usually connected to money

- Who does Candide and his group end up learning the most from? Note their religion. Why.

- How does Abigal’s philosophy “but always I loved life” (chap 12) play out in the world and in the novel?

- Why does Voltaire note that in Eldorado, the natives cannot leave (XVIII, 43)? What does this suggest?

- “At heart, Candide had no real wish to marry Cunegonde; but the baron’s extreme impertinence decided him in favor of the marriage, and Cunegonde was so eager for it that he could not back out” (chap 30). What does this quote show about Candide and about human nature?

- Conversation b/t Martin and Candide: Martin “the

shadows are horrible ugly blots.

– It is human beings who make the blots, said Candide, and they can’t do otherwise.

--Than it isn’t their fault, said Martin” (XXII; p 60)and the famous "hawks have always eaten pigeons" (XXI)

"You are very hard of belief"

"I have lived" (XXIV)Marin, the pessimist, is working a few different veins here. Is he correct? Does his logic hold up in the novel? Consider, for example, James the Anabaptist; Cacambo, etc.

- ***What do you make of Cacambo’s and Candide’s decision to leave Eldorado (chap 18); note what the king says “when you are pretty comfortable somewhere, you had better stay there” (chap 18)

- Small detail: why discuss the behavior of the Eldoradians at the hotel? Chap 17, 547.

- Why have the disfigured beggar in chapter 19? And what do you make of the line “This is the price of the sugar you eat in Europe”

- Chapter XIX (51) "if all things are good, it is in El Dorado and not in the rest of the world."

- Chapter XX "had the pleasure of seeing the fight at their ease" -- why pleasure? And note the long speech by Martin that comes before it "Even in those cities which seem to enjoy peace, and where the arts flourish, the inhabitants are devoured by more envy, care, and uneasiness than are experienced by a besieged town" (Chap XX, 53)

- Chap XXIII -- What's the purpose of this chapter? What does it suggest about the English? Why doesn't he go on shore?

- What? Chap XXIV "Upon their arrival at Venice, Candide went to search for Cacambo at every inn and alehouse, and among all the ladies of pleasure, but to no purpose" (66). What jumps out here? Why? And what does Brother Giroflee mean when he says "become a Turk"?

- XXV How is Pocurante a stereotypical American? Consider this car commercial. "Oh! what a superior man [ . . . .] What a great genius is this Pococurante! Nothing can please him" (73). Why does this impress Candide? How is this ironic? "there is some pleasure in having no pleasure."

- XXVIII: Pangloss is American -- or at least 15% of us.

- XXX 85: why a Dervish? (85) Why does he shut the door in Candide's face (86)?

- XXX Why does Giroflee become a joiner? What's a joiner?

- XXX Let's list the different translations of the cultivating our garden quote.

Question #1

- Three part questions: a) using the definitions on the humor handout, find examples of three in the text; b) How does he make these things funny? After all, what’s funny about getting “four thousand strokes”? Why do we laugh at these things. Choose two incidents, and explain; c) Another version of why which gets at Voltaire's intention and his art: why does he use humor? Why not treat these horrific events seriously? Is he trivializing these horrors? Explain with quotes please.

- Consider this comment by our buddy Bakhtin. After noting that festive humor is directed at the powerful (see definition), he adds

it is also directed at those who laugh. The people do not exclude themselves from the wholeness of the world. They, too, are incomplete, they also die and are revived and renewed. This is one of the essential differences of the people’s festive laughter from the pure satire of modern times. The satirist whose laughter is negative places himself above the object of his mockery, he is opposed to it. . . . The people’s ambivalent laughter, on the other hand, expresses the point of view of the whole world; he who is laughing also belongs to it” (Bakhtin Rabelais 12)

Is this true in Candide? Does the narrator “belong” in the world of the text? Is he laughing at or with the reader/people?

- The acclaimed English poet Alexander Pope, ends his poem "An Essay on Man," an explanation of how God's plan is evident on earth, with an clear statement: "One truth is clear, Whatever is, is right." Does Voltaire believe “whatever is, is right”? Offer specific examples and explanations of how those examples prove your point (yes, you need page numbers). For Voltaire, what are, to borrow Pope's motive for "An Essay," “the ways of God to man”?

- Make a list of the human foibles Voltaire satirizes; select one and find examples and prepare to explain them.

Question #2

- A few on Eldorado: a) How is Eldorado different from Europe? b) What does Eldorado symbolize? c) why do they leave?

- Why the travel around the world? Why not just confine the actions to Germany?

- While Voltaire is relentlessly satirical, there are some positive characters/actions in the text. List at least two and answer the following: What are they and from what does this goodness stem? What does this suggest about Voltaire’s view of the world?

- What’s worse in this novel, reality or denying reality? Find examples to prove your point.

- Is Candide still so simple at the end of the novel or has he grown/changed? Proof from the text please.

- Of course, the final scene. What does it mean to "cultivate our garden"? Is the ending pessimistic or optimistic?

How Extended Travel Affects Personality. Psychology Today, Art Markman: Sept. 10, 2013.

Chap XXIV and passim:

Mendez, Jeanette and Jesse Mendez. "Student Inferences Based on Facial Appearance." Higher Education (00181560), vol. 71, no. 1, Jan. 2016, pp. 1-19. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1007/s10734-015-9885-7.

| Voltaire as behavioral therapist

“In the United States, when it comes to improving health, people tend to focus on exercise and what we put into our mouths — organic foods, omega-3’s, micronutrients. We spend nearly $30 billion a year on vitamins and supplements alone. Yet in Ikaria and the other places like it, diet only partly explained higher life expectancy. Exercise — at least the way we think of it, as willful, dutiful, physical activity — played a small role at best. Social structure might turn out to be more important. In Sardinia, a cultural attitude that celebrated the elderly kept them engaged in the community and in extended-family homes until they were in their 100s. Studies have linked early retirement among some workers in industrialized economies to reduced life expectancy. In Okinawa, there’s none of this artificial punctuation of life. Instead, the notion of ikigai — “the reason for which you wake up in the morning” — suffuses people’s entire adult lives. It gets centenarians out of bed and out of the easy chair to teach karate, or to guide the village spiritually, or to pass down traditions to children. The Nicoyans in Costa Rica use the term plan de vida to describe a lifelong sense of purpose. As Dr. Robert Butler, the first director of the National Institute on Aging, once told me, being able to define your life meaning adds to your life expectancy.” (Buettner) “The big aha for me, having studied populations of the long-lived for nearly a decade, is how the factors that encourage longevity reinforce one another over the long term. For people to adopt a healthful lifestyle, I have become convinced, they need to live in an ecosystem, so to speak, that makes it possible. As soon as you take culture, belonging, purpose or religion out of the picture, the foundation for long healthy lives collapses. The power of such an environment lies in the mutually reinforcing relationships among lots of small nudges and default choices. There’s no silver bullet to keep death and the diseases of old age at bay. If there’s anything close to a secret, it’s silver buckshot” (Buettner) DAN BUETTNER “The Island Where People Forgot to Die.” New York Times. 24 October 2012. Web. 24 October |

"Living with Less. A Lot Less" by Graham Hill for a more modern band of pilgrims in NYC -- Soho to be exact.

Modern times? Read Generation Sell; [Op-Ed] William Deresiewicz. New York Times (Late Edition (East Coast)). New York, N.Y.: Nov 13, 2011.

"What Work is Really For." New York Times. September 8, 2012. Interesting essay by Gary Gutting on the real purpose of work and materialism. Voltaire would nod with agreement.

Cf. chapter III

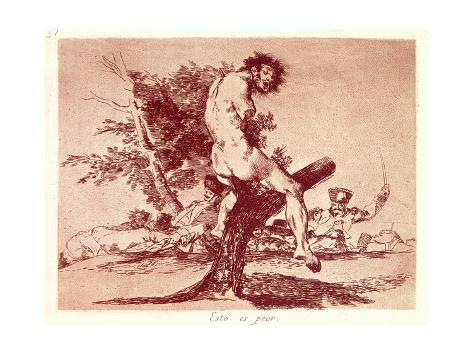

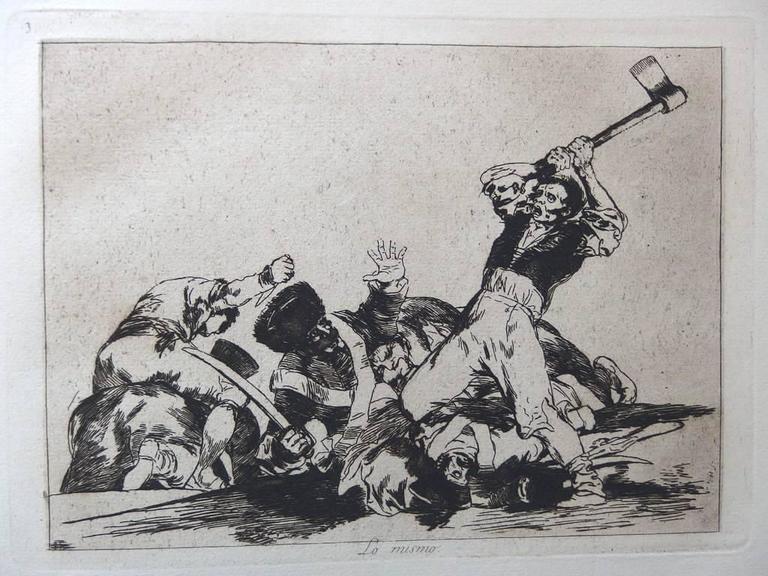

From Goya's The Disasters of War (circa 1810)

http://imgc.allpostersimages.com/images/P-473-488-90/81/8100/5BR2300Z/posters/francisco-de-goya-the-disasters-of-war.jpg

http://www.richardharrisartcollection.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/Li-Goya-plate19b-300x199.jpg

Links

A Candid View of Candide. Julian Barnes in The Guardian.

© 2018 David Bordelon