Lesson Plans

Course Links

Lesson Plans

Course

Documents Links

Secondary Sources

Quick Links

Library

Links

Citing

Sources

T. S. Eliot

Terms | Life | Times | Class Discussion | Group Questions | Links | Pictures | Quotes from Critics

Neil Hilborn "OCD"

Terms to Know

modernism: A general term applied

retrospectively to the wide range of experimental and avant-garde

trends in the literature

(and other arts) of the early 20th century, including Symbolism

, Futurism

, Expressionism

, Imagism

, Vorticism

, Ultraismo

, Dada

, and Surrealism

, along with the innovations of

unaffiliated writers. Modernist

literature is characterized chiefly by a rejection of 19th-century

traditions and of their consensus between author and reader: the

conventions of realism

, for instance, were abandoned by Franz

Kafka and other novelists, and

by expressionist drama, while several poets rejected traditional metres

in favour of free

verse . Modernist writers tended to see

themselves as an avant-garde

disengaged from bourgeois values, and disturbed their readers by

adopting complex and difficult new forms and styles. In fiction, the

accepted continuity of chronological development was upset by Joseph

Conrad , Marcel Proust , and William Faulkner , while James Joyce and

Virginia Woolf attempted new ways of tracing the flow of characters'

thoughts in their stream-of-consciousness

styles. In poetry, Ezra Pound and T. S.

Eliot replaced the logical exposition of thoughts with collages

of fragmentary images and complex allusions

. Luigi Pirandello and Bertolt Brecht

opened up the theatre to new forms of abstraction in place of realist

and naturalist

representation.

Modernist writing is predominantly cosmopolitan, and often expresses a

sense of urban cultural dislocation, along with an awareness of new

anthropological and psychological theories. Its favoured techniques of

juxtaposition and multiple point

of view challenge the reader to

reestablish a coherence of meaning from

fragmentary forms. In English, its major landmarks are Joyce's Ulysses

and Eliot's The Waste Land

(both 1922 ). In Hispanic literature the term has a special sense: modernismo

denotes the new style of poetry in Spanish from 1888

to c .1910 , strongly influenced by the French Symbolists

and Parnassians

and introduced by the Nicaraguan poet

Rubén Darío and the Mexican poet

Manuel Gutiérrez Nájera . For a fuller account, consult Peter Childs , Modernism

(2nd edn, 2007 ).

"modernism." The Oxford Dictionary of Literary

Terms . Chris Baldick. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford

Reference Online . Oxford University

Press. Ocean County College. 6

March 2009

Imagism:

poetic movement of England and the United States, flourished from 1909

to 1917. Its credo, expressed in Some Imagist Poets (1915), included

the use of the language of common speech, precision, the creation of

new rhythms, absolute freedom in choice of subject matter, the

evocation of images in hard, clear poetry, and concentration.

Originating in the aesthetic philosophy of T. E. Hulme, the movement

soon attracted Ezra Pound, who became the leader of a small group

opposed to the romantic conception of poetry and inspired by Greek and

Roman classics and by Chinese, Japanese, and modern French poets. In

the U.S., the group was represented in Poetry: A Magazine of Verse by

Pound, H. D., John Gould Fletcher, and Amy Lowell, and by such English

poets as F. S. Flint, Richard Aldington, and D. H. Lawrence. Pound

collected some of their work in Des Imagistes: An Anthology (1914),

after which his interest began to wane; Amy Lowell then assumed active

leadership, advocating that the group subscribe to a fixed program and

hold together for at least three years. Under her guidance were

published several anthologies, all entitled Some Imagist Poets.

"Imagism." The Concise Oxford Companion to American Literature.

James D. Hart. Oxford University Press, 1986. Oxford Reference Online.

Oxford University Press. Ocean County College. 10 March 2009

For a more thorough overview, see Scott Ashley "Imagism and American Poets" The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature . Jay Parini. Oxford University Press 2004. Oxford Reference Online . Oxford University Press.

The Life

See textbook for information on his life.

The Paris Review 1959

interview of T. S. Eliot

Another in this excellent series.

Eliot met and corresponded with most of the major figures of literary Modernism: Virginia Woolf, W. B. Yeats, James Joyce, Andre Gide, Marianne Moore, Pound, etc. And remember that while we're focusing on American versions of Modernism, it began in europe.

And though too much can be made of this, remember that his first marriage, to Vivian, was tortured, and many critics believe, sexually unfulfilling.

"The only way of expressing emotion in the form of art is by finding an "objective correlative"; in other words, a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately evoked." ("Hamlet")

Eliot, T. S. "Hamlet." The Sacred Wood: Essays on Poetry and Criticism, 1922. <http://www.bartleby.com/200/sw9.html>. 3 March 2009.

" The poet can deal with philosophic ideas, not as matter for argument, but as matter for inspection. The original form of a philosophy cannot be poetic. But poetry can be penetrated by a philosophic idea, it can deal with this idea when it has reached the point of immediate acceptance, when it has become almost a physical modification." ("Dante")

" The philosophy is an ingredient, it is a part of Dante's world just as it is a part of life; the allegory is the scaffold on which the poem is built." ("Dante" )

" Dante, more than any other poet, has succeeded in dealing with his philosophy, not as a theory (in the modern and not the Greek sense of that word) or as his own comment or reflection, but in terms of something perceived. When most of our modern poets confine themselves to what they had perceived, they produce for us, usually, only odds and ends of still life and stage properties" ("Dante")

Eliot, T. S. "Dante." The Sacred Wood: Essays on Poetry and Criticism, 1922. <http://www.bartleby.com/200/sw9.html>. 3 March 2009.

On his

influences:

"I became much more prolific, under the influence first of Baudelaire

and then of Jules Laforgue, whom I discovered I think in my junior year

at Harvard." (Hall)

On American poetry influences on his development as a poet: "I think it was rather an advantage not having any living poets in England or America in whom one took any particular interest. I don’t know what it would be like but I think it would be a rather troublesome distraction to have such a lot of dominating presences, as you call them, about." (Hall)

On Pound's editing of his poetry: "He was a marvelous critic because he didn’t try to turn you into an imitation of himself. He tried to see what you were trying to do" (Hall).

"I wonder what an "intention" means! One wants to get something off one’s chest. One doesn’t know quite what it is that one wants to get off the chest until one’s got it off. But I couldn’t apply the word "intention" positively to any of my poems. Or to any poem." (Hall)

'My early vers libre, of course, was started under the endeavor to practice the same form as Laforgue. This meant merely rhyming lines of irregular length, with the rhymes coming in irregular places. It wasn’t quite so libre as much vers, especially the sort which Ezra called "Amygism."* " (Hall)

On his poetry as part of an American tradition: "I’d say that my poetry has obviously more in common with my distinguished contemporaries in America than with anything written in my generation in England. That I’m sure of. " (Hall)

On America in his poetry: "But in its sources, in its emotional springs, it comes from America." (Hall)

Hall, Donald. "The Art of Poetry No. 1." The Paris Review. 21 (Spring/Summer 1959). <http://www.theparisreview.org/viewinterview.php/prmMID/4738>. 24 March 2009.

From "Tradition and the Individual Talent"

" we shall often find that not only the best, but the most individual parts of his work may be those in which the dead poets, his ancestors, assert their immortality most vigorously." (1582)

" Tradition is a matter of much wider significance. It cannot be inherited, and if you want it you must obtain it by great labour." (1582)

"the historical sense involves a perception, not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence; the historical sense compels a man to write not merely with his own generation in his bones, but with a feeling that the whole of the literature of Europe from Homer and within it the whole of the literature of his own country" (1582)

" No poet, no artist of any art, has his complete meaning alone. His significance, his appreciation is the appreciation of his relation to the dead poets and artists." (1582)

" what happens when a new work of art is created is something that happens simultaneously to all the works of art which preceded it. The existing monuments form an ideal order among themselves, which is modified by the introduction of the new (the really new) work of art among them. The existing order is complete before the new work arrives; for order to persist after the supervention of novelty, the whole existing order must be, if ever so slightly, altered" (1582-83)

" Honest criticism and sensitive appreciation is directed not upon the poet but upon the poetry." (1583)

" It is not in his personal emotions, the emotions provoked by particular events in his life, that the poet is in any way remarkable or interesting." (1583)

On Difficulty in Poetry

Eliot, T. S. Review of "Metaphysical Lyrics and Poems of the Seventeenth Century: Donne to Butler, selected and edited, with an essay, by Herbert J. C. Grierson." Times Literary Supplement. 20 October 1921. Centenary College. Web. 26 March 2013.

"It is not a permanent necessity that poets should be interested in philosophy, or in any other subject. We can only say that it appears likely that poets in our civilization, as it exists at present, must be difficult. Our civilization comprehends great variety and complexity, and this variety and complexity, playing upon a refined sensibility, must produce various and complex results. The poet must become more and more comprehensive, more allusive, more indirect, in order to force, to dislocate if necessary, language into his meaning. (A brilliant and extreme statement of this view, with which it is not requisite to associate oneself, is that of M. Jean Epstein, La Poesie d'aujourd-hui.) Hence we get something which looks very much like the conceit - we get, in fact, a method curiously similar to that of the 'metaphysical poets', similar also in its use of obscure words and of simple phrasing."

How do these comments explain the obscurity and complexity of Eliot's verse?

The Times

Essay on cultural and historical background of The

Waste Land

T. S. Eliot: The Waste Land, in Literature and Its Times: Profiles of

300 Notable Literary Works and the Historical Events that Influenced

Them, Volume 3: Growth of Empires to the Great Depression (18901930s),

edited by Joyce Moss and George Wilson, Gale Research, 1997. Reproduced

in Literature Resource Center.

From Autobiography of William Carlos Williams

On the publication of "The Waste Land" in the Dial : "It wiped out our world as if an atom bomb had been dropped upon it and our brave sallies into the unknown were turned to dust.

"To me especially it struck like a sardonic bullet. I felt at once that it had set me back twenty years, and I'm sure it did. Critically Eliot returned us to the classroom just at the moment when I felt that we were on the point of an escape to matters much closer to the essence of a new art form itself -- rooted in the locality which should give it fruit. I knew at once that in certain ways I was most defeated.

"Eliot had turned his back on the possibility of reviving my world. And being an accomplished craftsman, better skilled in some ways than I could ever hope to be, I had to watch him carry my world off with him, the fool, to the enemy." (174)

From Civilization in the United States: An Inquriy by Thirty Americans edited by Harold Stearns (1922 written in 1921)

the most moving and pathetic fact in the social life of America to-day is emotional and aesthetic starvation, of which the mania for petty regulation, the driving, regimentating, and drilling, the secret society and its grotesque regalia, the firm grasp on the unessentials of material organization of our pleasures and gaieties are all eloquent stigmata. We have no heritages or traditions to which to cling except those that have already withered in our hands and turned to dust. One can feel the whole industrial and economic situation as so maladjusted to the primary and simple needs of men and women that the futility of a rationalistic attack on these infantilisms of compensation becomes obvious. There must be, an entirely new deal of the cards in one sense; we must change our hearts. For only so, unless through the humbling of calamity or scourge, can true art and true religion and true personality, with their native warmth and caprice and gaiety, grow up in America to exorcise these painted devils we have created to frighten us away from the acknowledgment of our spiritual poverty. (Stearns vii)

- Modernism: "Make it new!"

- Friends with Ezra Pound, who the poem is dedicated to. Both poets profoundly influenced by WW1. Go to "Homage" IV -- more so V "There died a myriad . . ."

- Tradition and the individual talent -- explain the role of poetic tradition in Eliot's work

- Oddly paradoxical: wants both to keep tradition yet keep the vernacular.

- Disassociation of Sensibility

- How does Eliot view urban life? Is there a positive view of rural life?

- "He do the policeman in different voices" why this title? Are there different voices here? Where?

"Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock"

- Remember that the poem is a dramatic monologue -- it's addressed to a person/s.

- Who's the "I" and "you" in the poem?

- The speaker is probably not Eliot -- he's an aged Victorian. Note that the title of the volume the poem appeared in is Prufrock and Other Observations.

- Who is Prufrock? What kind of man is he? Fix him with a "formulated phrase," and then use quotes to prove that point.

- Now refute the above. How is he not what he appears. Prove with quotes

- Lacking a set rhyme scheme or a stanzas, the poem seems like fragmented lines/thoughts. Do they cohere? Yes/no -- prove with quotes.

"Hollow Men"

- Who are the "Hollow Men"? Do they still exist today? Proof from poem and real life.

cf. Marlowe's comment in Heart of Darkness on one of the men he meets in an African camp

"I let him run on, this _papier-mache_ Mephistopheles, and it seemed to me that if I tried I could poke my forefinger through him, and would find nothing inside but a little loose dirt, maybe. He, don't you see, had been planning to be assistant-manager by and by under the present man, and I could see that the coming of that Kurtz had upset them both not a little."

And Kurtz himself is hollow: " But the wilderness had found him out early, and had taken on him a terrible vengeance for the fantastic invasion. I think it had whispered to him things about himself which he did not know, things of which he had no conception till he took counsel with this great solitude--and the whisper had proved irresistibly fascinating. It echoed loudly within him because he was hollow at the core."

"Gerontion"

What seems to beset this man? What seems to be holding him back?

The Waste Land

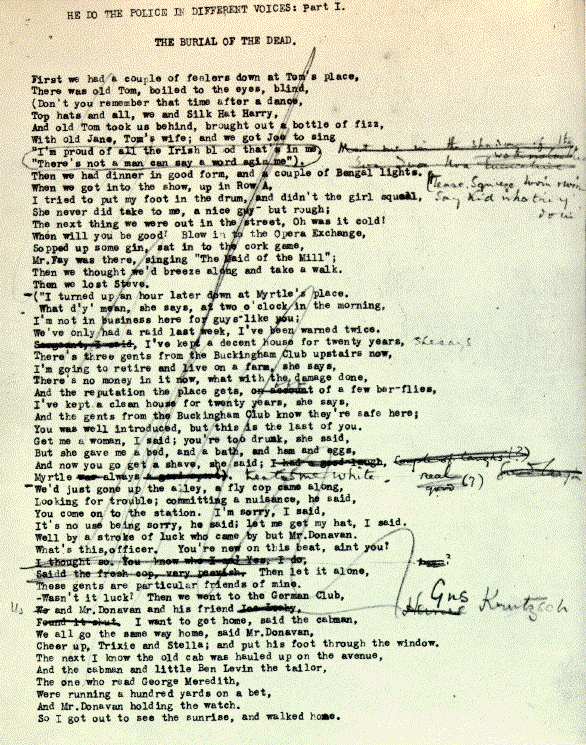

First page of draft of Wasteland. Note how much was deleted.

Draft page of the Wasteland with Pound's suggestions

Click for page in Dial magazine where poem first appeared

- Eliot in his the Dante essay, wrote "genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood" (qtd. in Ellis 53): is this true? Is it true here?

- Some quick background before we engage with the poem itself.

- European element: Baudlaire; James Joyce Ulysses ; Max Ernst 1934

- Disassociation of sensibility " The poets of the seventeenth century, the successors of the dramatists of the sixteenth, possessed a mechanism of sensibility which could devour any kind of experience. They are simple, artificial, difficult, or fantastic, as their predecessors were; no less nor more than Dante, Guido Cavalcanti, Guinicelli, or Cino. In the seventeenth century a dissociation of sensibility set in, from which we have never recovered; and this dissociation, as is natural, was aggravated by the influence of the two most powerful poets of the century, Milton and Dryden.

• This is the idea that feeling ("sensibility") had become separated from thought ("experience") in poetry after the metaphysics. Eliot believed feeling and thought needed to be reunited.

- Tradition and the individual talent

- Objective correlative "The only way of expressing emotion in the form of art is by finding an "objective correlative"; in other words, a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately evoked." ("Hamlet")

- "Make it strange, make it different, make it surprising, make it mysterious, make it elliptical, make it discontinuous, make it kaleidoscopic -- these were all ways to 'make it new,' as Pound exhorted his peers. Examination of three techniques -- multiple perspectives, juxtaposition, and allusion -- will introduce the much larger range of invention that characterizes many modernist texts. As will become clear, the three techniques are often interdependent" (McDonald 142).

- Original title "He do the Policeman in Different Voices" -- how does this work?

- How is the poem divided? Does this connect with the original title?

- What label would you put on each section? Section

- Why so many allusions to classical literature? What do they add to the poem and/or Eliot's intention in the poem?

• For instance, compare the opening of Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales with the opening of "The Waste Land"

WHEN that Aprilis, with his showers swoot*, *sweet

The drought of March hath pierced to the root,Is The Waste Land also a pilgrimage? How so?

- What's so bad about April? Why make it symbolic?

- Eliot's notes are a point of critical contention: are they, as Eliot suggested, mere padding, or do they add to the poem? Can they be both?

- Assemblage Why the mixture of times? We go from ancient times to modern London. What's the usual setting in the poem? Rural? Urban? Is there any difference in the times? What is he suggesting about all of these periods?

- Civilization in the United States: An

Inquriy by Thirty Americans

edited by Harold Stearns (1922 written in 1921), captures the mood of

American intellectuals after World War I. In a series of essays by

various hands, nearly every aspect of American culture is tested and

found wanting" (McDonald 113). Its editor wrote the following:

First, That in almost every branch of American life there is a sharp dichotomy between preaching and practice: we let not our right hand know what our left hand doeth. Curiously enough, no one regards this, and in fact no one consciously feels this as hypocrisy--there are certain abstractions and dogmas which are sacred to us, and if we fall short of these external standards in our private life, that is no reason for submitting them to a fresh examination; rather are we to worship them the more vociferously to show our sense of sin. Regardless, then, of the theoretical excellence or stupidity of these standards, in actual practice the moral code resolves itself into the one cardinal heresy of being found out, with the chief sanction enforcing it, the fear of what people will say.

Second, That whatever else American civilization is, it is not Anglo-Saxon, and that we shall never achieve any genuine nationalistic self-consciousness as long as we allow certain financial and social minorities to persuade us that we are still an English Colony. Until we begin seriously to appraise and warmly to cherish the heterogeneous elements which make up our life, and to see the common element running through all of them, we shall make not even a step towards true unity; we shall remain, in Roosevelt's class-conscious and bitter but illuminating phrase, a polyglot boarding-house. It is curious how a book on American civilization actually leads one back to the conviction that we are, after all, Americans.

Third That the most moving and pathetic fact in the social life of America to-day is emotional and aesthetic starvation, of which the mania for petty regulation, the driving, regimentating, and drilling, the secret society and its grotesque regalia, the firm grasp on the unessentials of material organization of our pleasures and gaieties are all eloquent stigmata. We have no heritages or traditions to which to cling except those that have already withered in our hands and turned to dust. One can feel the whole industrial and economic situation as so maladjusted to the primary and simple needs of men and women that the futility of a rationalistic attack on these infantilisms of compensation becomes obvious. There must be, an entirely new deal of the cards in one sense; we must change our hearts. For only so, unless through the humbling of calamity or scourge, can true art and true religion and true personality, with their native warmth and caprice and gaiety, grow up in America to exorcise these painted devils we have created to frighten us away from the acknowledgment of our spiritual poverty. (Stearns vi-vii)

- If you're trying to be different, trying to break with artistic tradition (Woolf's Mrs. Bennet and Mr. Brown; Cather's novels of entertainment v. novels of art), what's the problem with linear narrative? Which is more realistic, linear narrative or disjointed narrative? Einstein's theory of relative (1905) did what to our concept of time? Conrad Aiken: "The poem succeeds -- as it brilliantly does -- by virtue of its incoherence, not of its plan; by virtue of its ambiguities, not of its explanations" (qtd. in Ellis 49). William Bishop "IMMENSE, TERRIBLE, MAGNIFICANT" (qtd. in Ellis 50)

- What role does the fertility myth play in this poem? Check, especially, for sexual images -- and what they are often linked with. (RENEWAL V. DECAY)

- A game of Chess section in the Waste Land "gathers up a number of the imagistic, thematic, and allusive threads of Eliot's poem: the destruction of life in war, the battering of beauty, conflict and failed communication between the sexes -- a depiction of postwar society as literally and figuratively drought-ridden, infertile, and damaged" (McDonald 123).

- Consider how the following

critique: "The imagery and episodes of Part One evoke a person, indeed

a civilization, numbed, distressed. Coherence and meaning have gone out

of the world," (Torrens) helps you understand the poem

In his review of a collection of Metaphysical Poetry, Eliot famously wrote: "We can only say that it appears likely that poets in our civilization, as it exists at present, must be difficult. Our civilization comprehends great variety and complexity, and this variety and complexity, playing upon a refined sensibility, must produce various and complex results. The poet must become more and more comprehensive, more allusive, more indirect, in order to force, to dislocate if necessary, language into his meaning."

In the same essay, he also offered his famous theory of the disassociation of sensibility in poetry

The poets of the seventeenth century, the successors of the dramatists of the sixteenth, possessed a mechanism of sensibility which could devour any kind of experience. They are simple, artificial, difficult, or fantastic, as their predecessors were; no less nor more than Dante, Guido Cavalcanti, Guinicelli, or Cino. In the seventeenth century a dissociation of sensibility set in, from which we have never recovered; and this dissociation, as is natural, was aggravated by the influence of the two most powerful poets of the century, Milton and Dryden.

This is the idea that feeling ("sensibility") had become separated from thought ("experience") in poetry after the metaphysics. Eliot believed feeling and thought needed to be reunited.

Eliot, T. S. "The Metaphysical Poets." Times Literary Supplement. 20 October 1921.

- Given these poems, what seems to be lacking in modern life? What is missing?

- Language and communication seem paramount in "Prufrock." How and why?

- Roger Mitchell argues that " J. Alfred Prufrock is not just the speaker of one of Eliot's poems. He is the Representative Man of early Modernism. Shy, cultivated, oversensitive, sexually retarded (many have said impotent), ruminative, isolated, [and] self-aware to the point of solipsism."

Trace this catalog of traits through the poem and then explain how it effects his view/personality. And consider how the presentation of his character -- stream of consciousness -- also is indicative of early Modernism.

- What holds back the "Song"? What seems to prevent him from professing his love?

- "Prufrock" appears to lacks a set rhyme scheme or stanzas; the poem seems like fragmented lines/thoughts. Do they cohere? Yes/no -- prove with quotes.

- Why Dante (What city did he visit)? Why bring up Hamlet (what was he known for not doing)? What does their inclusion (and other illusions to Michelangelo, etc.) suggest about the speaker of the poem?

Questions on The Waste Land

- What role does water play in this poem?

- Why repeat "Unreal" (60, 207, 377) so many times?

- How are women characterized in this poem?

- There are two broad interpretations of this poem: a) it is a "poem of radical doubt and negation, urging that every human desire be stilled except the desire for self-surrender, for restraint, and for peace" (Hay) or b) a poem of regeneration, a 20th century version of the grail myth. Which reading do you find more valid? Why?

- Our friend William Carlos Williams famously noted

that the publication of "The Waste Land" in the Dial

wiped out our world as if an atom bomb had been dropped upon it and our brave sallies into the unknown were turned to dust. To me especially it struck like a sardonic bullet. I felt at once that it had set me back twenty years, and I'm sure it did. Critically Eliot returned us to the classroom just at the moment when I felt that we were on the point of an escape to matters much closer to the essence of a new art form itself -- rooted in the locality which should give it fruit. I knew at once that in certain ways I was most defeated.

- Another long quote alert:

From Civilization in the United States: An Inquriy by Thirty Americans edited by Harold Stearns (1922 written in 1921)

the most moving and pathetic fact in the social life of America to-day is emotional and aesthetic starvation, of which the mania for petty regulation, the driving, regimentating, and drilling, the secret society and its grotesque regalia, the firm grasp on the unessentials of material organization of our pleasures and gaieties are all eloquent stigmata. We have no heritages or traditions to which to cling except those that have already withered in our hands and turned to dust. One can feel the whole industrial and economic situation as so maladjusted to the primary and simple needs of men and women that the futility of a rationalistic attack on these infantilisms of compensation becomes obvious. There must be, an entirely new deal of the cards in one sense; we must change our hearts. For only so, unless through the humbling of calamity or scourge, can true art and true religion and true personality, with their native warmth and caprice and gaiety, grow up in America to exorcise these painted devils we have created to frighten us away from the acknowledgment of our spiritual poverty. (Stearns vii)

How are these ideas portrayed in Eliot's work, both "The Waste Land" and "Prufrock"?

- Yet another long quote alert:

In his review of a collection of Metaphysical Poetry, Eliot famously wrote: "We can only say that it appears likely that poets in our civilization, as it exists at present, must be difficult. Our civilization comprehends great variety and complexity, and this variety and complexity, playing upon a refined sensibility, must produce various and complex results. The poet must become more and more comprehensive, more allusive, more indirect, in order to force, to dislocate if necessary, language into his meaning."

How does this dislocation, complexity, variety make the poem more "difficult"? Since this is what Eliot is going for, how does it help the poem?

- What connections can you make between Eliot's poetry and Pound's? Between Eliot's and other poets we discussed?

How is Williams correct? How could this work "defeat" his view of art? How is it different from Williams?

Links

Photo

essay on World War I

Exploring

the Waste Land

Intriguing site that offers a hypertext (and more . . . much, much more

. . .) on the poem. You should really check this out.

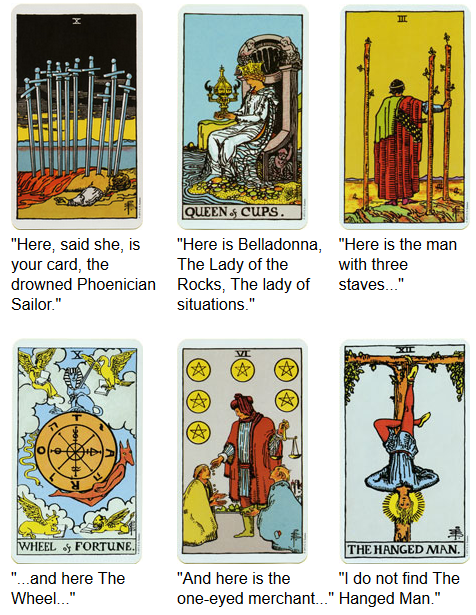

images from

http://crossroadstarot.com/thewastelandandtarot.htm

Quotes from Critics

See Modern American Poet web site for a fine list of quotes on Eliot.

Quotes below taken from http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/a_f/eliot/general.htm

Stephen Spender

"Ritualistic" is, it seems to me, the word that best describes [Eliot's] attitude to life. He had a vision of the relationship of the living with the dead through the patterns of rituals that extend into the modern world the pieties that remain unaltered from the past. He thought that when these rituals were disrupted -- and when, in deed, the observance of them was not the foremost aim of the living -- there would be no connection of the living with the dead, of the present with the past.

From T.S. Eliot (New York: Viking

Press, 1975): 7

J. Hillis Miller

This is the situation to which romanticism in poetry and idealism in philosophy have brought Eliot. Each man seems destined to remain enclosed in his separate sphere, unable to break out to external things, to other people, to an objective time and space, or to God. All these exist, but as qualifications of the inner world which is peculiar and private to the self.

Perhaps it will be possible to accept this situation and make a tolerable life out of it. Instead of beating futilely against the walls of its prison, the self should turn within, inspect the contents of inner space, and try to reduce them to harmony. Though all things are only modes of the self they do have at least that form of existence. If they can be put in patterned order the self, though still isolated, will be like a little world made cunningly. A world of this sort, the universe squeezed into a ball, may not possess God as the immanent principle of its order, but it may have that secondary form of possession which is called resonance.

The notion of attunement is of great importance for Eliot. It is one reason why he gives so much value to formal design. Pattern is not so much a good in itself as it is a means of reaching the otherwise unattainable stillness at the center. The finite self is hopelessly peripheral, but if its elements can be brought into order they may vibrate, though at an infinite distance, in harmony with the divine pattern. This bringing into order is Eliot's fundamental definition of art. Though art and religion are always to be distinguished, art is not an end in itself. It can take man only part of the way toward salvation, but its reason for being is precisely to take him that part of the way. This it does through an ordering of reality which leads to an artistic stillness oriented toward the divine stillness and echoing it.

This is the meaning of Eliot's most explicit definition of the use of art: "For it is ultimately the function of art, in imposing a credible order upon ordinary reality, and thereby eliciting some perception of an order in reality, to bring us to a condition of serenity, stillness, and reconciliation; and then leave us, as Virgil left Dante, to proceed toward a region where that guide can avail us no farther" (OPP, 94). The passage is another version of an ambiguity basic in romanticism from Keats and Shelley to Yeats. just as Yeats, in Ideas of Good and Evil, cannot decide whether the poet "creates" or "reveals" his symbols, so art for Eliot imposes pattern in order to reveal one which has been there invisibly all along. This pre-existent order is shy to reveal itself and can be brought to light only by a created order, the "musical design" (OPP, 80) of art. The pattern in reality may be there already, but it is brought into being for human beings only through art. Art is the Virgil who leads us to the borders of that realm where only Beatrice can lead us farther. Such a notion of art as design vibrating in resonance with the divine stillness is, in "Burnt Norton," admirably expressed in the image of the Chinese jar:

Words, after speech, reach

Into the silence. Only by the form, the pattern,

Can words or music reach

The stillness, as a Chinese jar still

Moves perpetually in its stillness.

Abandoning his impotent yearning to escape from himself, the poet turns inward to search within his own sphere for the patterns which may grant him an indirect possession of the divine harmony. It may be that the inner world of the isolated ego falls naturally into orderly design.

From Poets of Reality: Six Twentieth-Century Writers . Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard UP. 1965.

© David Bordelon 2009