Lesson Plans

Course Links

Lesson Plans

Course Documents Links

Secondary Sources

Quick Links

Library Links

Citing Sources

e. e. cummings (1894-1962); Marianne Moore (1887-1972)

|

|

Terms | Life | Times | Class Discussion | Group Questions | Links | Pictures | Quotes from Critics

Terms to KnowIrony: A subtly humorous perception of inconsistency, in which an apparently straightforward statement or event is undermined by its context so as to give it a very different significance. In various forms, irony appears in many kinds of literature, from the tragedy of Sophocles to the novels of Jane Austen and Henry James , but is especially important in satire , as in Voltaire and Swift. At its simplest, in verbal irony, it involves a discrepancy between what is said and what is really meant, as in its crude form, sarcasm; for the figures of speech exploiting this discrepancy, see antiphrasis, litotes, meiosis . The more sustained structural irony in literature involves the use of a naïve or deluded hero or unreliable narrator , whose view of the world differs widely from the true circumstances recognized by the author and readers; literary irony thus flatters its readers' intelligence at the expense of a character (or fictional narrator). A similar sense of detached superiority is achieved by dramatic irony, in which the audience knows more about a character's situation than the character does, foreseeing an outcome contrary to the character's expectations, and thus ascribing a sharply different sense to some of the character's own statements; in tragedies , this is called tragic irony. The term cosmic irony is sometimes used to denote a view of people as the dupes of a cruelly mocking Fate, as in the novels of Thomas Hardy . A writer whose works are characterized by an ironic tone may be called an ironist. For a fuller account, consult Claire Colebrook , Irony ( 2003 ).

"irony." The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Chris Baldick. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Ocean County College. 29 March 2009.

Satire: A mode of writing that exposes the failings of individuals, institutions, or societies to ridicule and scorn. Satire is often an incidental element in literary works that may not be wholly satirical, especially in comedy . Its tone may vary from tolerant amusement, as in the verse satires of the Roman poet Horace , to bitter indignation, as in the verse of Juvenal and the prose of Jonathan Swift (see juvenalian ). Various forms of literature may be satirical, from the plays of Ben Jonson or of Molière and the poetry of Chaucer or Byron to the prose writings of Rabelais and Voltaire . The models of Roman satire, especially the verse satires of Horace and Juvenal, inspired some important imitations by Boileau , Pope , and Johnson in the greatest period of satire--the 17th and 18th centuries--when writers could appeal to a shared sense of normal conduct from which vice and folly were seen to stray. In this classical tradition, an important form is ‘formal’ or ‘direct’ satire, in which the writer directly addresses the reader (or recipient of a verse letter) with satiric comment. The alternative form of ‘indirect’ satire usually found in plays and novels allows us to draw our own conclusions from the actions of the characters, as for example in the novels of Evelyn Waugh or Chinua Achebe . See also lampoon . For a range of introductory accounts, consult Ruben Quintero (ed.), A Companion to Satire ( 2006 ).

"satire." The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Chris Baldick. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Ocean County College. 29 March 2009.

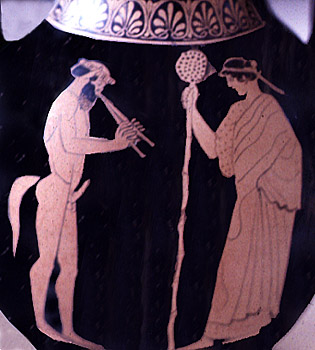

satyr: in Greek mythology, one of a class of lustful, drunken woodland gods. In Greek art they were represented as a man with a horse's ears and tail, but in Roman representations as a man with a goat's ears, tail, legs, and horns.

In English translations of the Bible the word is applied to the hairy demons or monsters of Semitic superstition, supposed to inhabit deserts, as in Isaiah 13:21.

"satyr." A Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. Edited by Elizabeth Knowles. Oxford University Press, 2006. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Ocean County College. 29 March 2009.

Dial, The (1880–1929): monthly journal of literary criticism, was founded at Chicago as a conservative review. In 1892 it became a fortnightly, continuing the original policy until 1918, when it was moved to New York. New contributing editors, including Conrad Aiken, H.E. Stearns, Randolph Bourne, and Van Wyck Brooks, made it a radical journal of opinion, publishing such previously taboo authors as Dewey, Veblen, Laski, Beard, and R.M. Lovett. Under Scofield Thayer, after 1920, The Dial became the most distinguished literary monthly in the U.S. to champion modern artistic movements. It drew contributors from many nations and had as associates Thomas Mann, T.S. Eliot, James Stephens, and Paul Morand. It printed virtually all the distinguished authors of the period, and was noted also for its fine reproductions of modern graphic art. Marianne Moore was editor after 1926.

"Dial, The." The Oxford Companion to American Literature. James D. Hart, ed., rev. Phillip W. Leininger. Oxford University Press 1995. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Ocean County College. 29 March 2009.

The Life

cummings

In addition to the introduction in the textbook, two excellent short biographies on cummings can be found on the Modern American Poetry site.

Moore

Born ten months earlier than T. S. Eliot in the same city: St. Louis. Spent much of her time in the biology lab at Bryn Mawr. Friends with William Carlos Williams, Pound, Eliot, Wallace Stevens.

Edited the Dial for a short time.

The Paris Review 1961 interview of Marianne Moore

Another in this excellent series.

See the textbook and this short biography on Moore from the Modern American Poetry site.

The Times

Still in the midst of the Modern age -- industrialism, war, peace, experimentation, etc. is at the fore.

Satire and irony are two of cummings' tools.

"i & now & him: NONLECTURE FIVE"

...I recognize immediately three mysteries: love, art, and selftranscendence or growing.

...Art is a mystery; all mysteries have their source in a mystery-of-mysteries who is love: and if lovers may reach eternity directly through love herself, their mystery remains essentially that of the loving artist whose way must lie through his art, and of the loving worshipper whose aim is oneness with his god. From another point of view, every human being is in and of himself or herself illimitable; but the essence of his or of her illimitability is precisely its uniqueness--nor could all poetry (past present and future) begin to indicate the varieties of selfhood; and consequently of selftranscendence.

cummings wrote "The day of the spoken lyric is past," he proclaimed. "The poem which has at last taken its place does not sing itself; it builds itself, three dimensionally, gradually, subtly, in the consciousness of the experiencer." How is this, especially the idea of building poetry, seen in his work?

"in Just-"

- what's different about the children in the poem? why?

- Why the progression of the balloonman (note capitalization)? Why whistling? What's a satyr? Who's Pan?

- what are the children going to do by the end of the poem?

- why spring? Why the emphasis on mud?

- why the breakdown of lines at the end of the poem? What effect does this have when you read the poem aloud?

- Does the balloonMan ultimately seem like a lech or like a more positive figure?

- "'in Just-' is grouped with poems called "Chansons Innocentes" alluding to William Blake's Songs of Innocence and the complementary Songs of Experience" (Labriola). How does this information, and the idea of "Innocence and experience, or the transition from the one state to the other" (Labriola) inform your understanding of this poem?

"O sweet spontaneous"

- Why is the earth sweet? why spontaneous?

- What's the connection between earth and religion?

- Why the images of sexuality?

- Earth a lover of death? why rhythmic lover?

- Why the separation of the last lines?

"Buffalo Bill's"

- sic transit gloria mundi "Thus passes the glory of the world." How does the poem illustrate this latin epigram?

- Read this poem aloud following the cues from the way the words are laid out on the page.

- Consider the pacing of the lines and combined words.

- Who is Buffalo Bill? What does he stand for in America?

- Why "defunct" and not dead?

- Tone? Sarcasm? Irony? Why "Mister Death"?

- David Ray has an interesting of this poem: "though the poem appears to be a simple elegy, it must be placed in the context of Cummings's obstinate attitude of hatred toward an American culture that invites children (and even men) to create an unworthy gallery of heroes." How is this so?

"the Cambridge ladies who live in furnished souls"

- Form of this poem?

- Connotations of Cambridge? Why not Brick ladies?

- "furnished souls"? how so?

- "unbeautiful"? how can a mind be "comfortable"?

- Christ and Longfellow?

- "interested" in so many things

- "present > permanent" why?

- Why the question mark on the Poles?

- Why the last image?

"next to of course god america I"

- Who is the speaker?

- What does he/she speak in?

- Why "jingo"?

- By mixing these lines in this way, what is he doing to them? What does he imply about the speaker and by extension those listening?

- How have these words lost their meanings? Yet what would happen if you criticize these words?

- Why the water? Why end the poem in this matter?

- Is the message in "Next to" still relevant? Has American patriotic discourse moved beyond this?

"i sing of Olaf glad and big"

- Allusion to Virgil's the Aeneid: "I sing of arms and the man" -- we have a different hero here. Why make this allusion? What does this do to the poem?

- Connected to the allusion to such a classic work, what's the tone of the speaker? Why use this tone?

- Consider the following from Gary Lane:

"Heroic epic... is based on communal values; a hero's greatness is a measure of the degree to which he exemplifies the qualities his society most prizes. With Olaf it is different. He must give up not merely his life but also the good name that valiance customarily wins, the hero's renown and reputation.... He can do so lightly, however, defying both the military force of his nation and its massively conformed opinions, because he answers to an individual rather than a collective truth, to personal vision rather than social regard."

How is this true in the poem?

- What's Olaf's tone? Why?

- Describe Olaf? What's his characteristics?

- How does irony function in this poem?

- What's happening in lines 9-15?

- Pay attention to the rhymed words. How do they lend meaning to the poem?

- What statistics are referred to at the end of the poem?

- How was Olaf more brave? What's meant by more blond?

- How is this poem relevant?

"somewhere i have never traveled, gladly beyond"

- How are seasons used in this poem? Why?

- Why use a flower as the main metaphor here?

- Why does the snow come in?

- "intense fragility"? huh? oxymoronic. What's he getting at?

- how can an intense fragility have "countries"?

- How/why does the last line work?

"anyone lived in a pretty how town"

- How do the seasons function in this poem?

Marianne Moore (circa 1920s)

"Poetry"

- Why dislike poetry? But does she really dislike it? What does she really dislike? Why?

"The Mind is an Enchanting Thing"

- What does enchanted mean? How could the rational mind be this?

- Why all the negatives "the mind / feeling its way as though blind"

- "'in Just-' is grouped with poems called "Chansons Innocentes" alluding to William Blake's Songs of Innocence and the complementary Songs of Experience" (Labriola). How does this information, and the idea of "Innocence and experience, or the transition from the one state to the other" (Labriola) inform your understanding of this poem?

- On "Buffalo Bill's" David Ray has an interesting of this poem: "though the poem appears to be a simple elegy, it must be placed in the context of Cummings's obstinate attitude of hatred toward an American culture that invites children (and even men) to create an unworthy gallery of heroes." How is this so?

- "Next to, of Course" has an odd last line. What's your reading of it? What is its purpose?

- Is the message in "Next to" still relevant? Has American patriotic discourse moved beyond this?

- What does Moore dislike about poetry? What does she like about poetry?

Links

e. e. cummings on the Modern American Poetry site

A fine collection cummings' art work is found on the paintings of e. e. cummings. And a valentine's card is posted on the New York Times web site.

Moore on the Modern American Poetry site

Quotes from Critics

See the Modern American Poetry site for excerpts from essays and other works on Moore and cummings.

© David Bordelon 2009