Lesson Plans

Course Links

Lesson Plans

Course Documents Links

Secondary Sources

Quick Links

Library Links

Citing Sources

Tennessee Williams

The Glass Menagerie

1944

Image from http://sfs.scnu.edu.cn/tanwh/tina3/s/spic/5.jpg

Terms | Life | Times | Class Discussion | Group Questions | Links | Pictures | Quotes from Critics

Terms to Know

The Great Depression: The Great Depression, the worst and longest contraction ever of the American economy, began in 1929 and lasted until 1941. For more than a decade, the American people experienced record levels of unemployment and poverty. At the depth of the Great Depression, in the winter of 1932–33, unemployment was at least one-fourth of the workforce, and national income had dropped by more than 50 percent. From 1933 to 1937, significant economic expansion occurred, although it fell far short of full recovery; and then the recession of 1937–38 sent economic indexes plummeting again. Not until defense spending began to stimulate the economy in 1940–41 did the depression end. In addition to its economic and human impact, the Great Depression affected virtually every aspect of American life, and brought a transformation of American politics by enabling the victory of Franklin D. Roosevelt in the presidential election of 1932. Roosevelt's presidency produced the New Deal and made the Democratic Party the nation's majority party for decades to come. The depression of the 1930s was thus "great" not only in its magnitude but also in its widespread and far-reaching consequences.

For remainder of essay, click here.

Jeffries, John W. "Great Depression." In Jeffries, John W., Katherine Liapis Segrue, and Gary B. Nash, eds. Encyclopedia of American History: The Great Depression and World War II, 1929 to 1945. vol. 8. New York: Facts On File, Inc., 2003. American History Online. Facts On File. Ocean County College Library. 22 April 2009.

The Life

See textbook for biographical information or

Tennessee Williams by Thomas P. Adler in Twentieth-Century American Dramatists: Fifth Series. Ed. Garrett Eisler. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 341 . Detroit: Gale, 2008. From Literature Resource Center.

The Times

We're still in the south here, but move here from reading short stories and novels to reading drama -- which is a bit of an oxymoron: how can you "read" something that supposedly only exists when it is performed? And that is one of the dilemmas of reading a play, as opposed to watching it unfold on a stage in a darkened room surrounded by strangers.

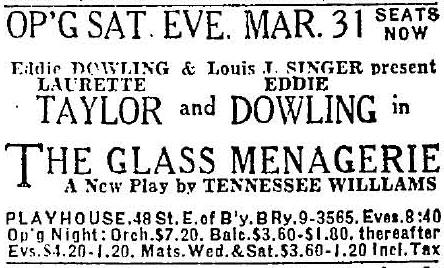

Advertisement for an early performance of The Glass Menagerie -- note the prices

Remember in a play there is no third person to reveal the inner workings of a character's mind -- unless the writers uses a convention of a soliloquy (an actor speaking directly to the audience which understands that the character is revealing what is on his/her mind -- Tom at the beginning and throughout this play) or a character whose purpose is to comment on the actions of other characters (the stage manager in Our Town for instance).

Thus, the dialogue, as in real life, means all. Of course, characters reveal themselves by what they say, and here the revelations come fast and furious. Pay attention to the stage directions and be sensitive to the different tones words can have in a conversation.

And as we've seen throughout the semester, writers delight in subverting reader's expectations, so pay attention to actions of seemingly innocuous characters like "a nice, ordinary, young man" (1974) and how they may comment on much broader concerns.

Written in 1944 (from short story titled "Portrait of a Girl in Glass" to screenplay titled "The Gentleman Caller"), the play takes for granted that its audience will catch many of the allusions. For instance, in Tom's first speech, he says "In Spain there was Guernica!" (1975) to which you may respond "huh?" or "that's nice" or, if you've taken Art History II "Didn't Matisse do a painting with that name."

Actually, it was Picasso.

And it's not so much the painting itself as the impetus behind the painting that Tom/Williams is alluding to. The painting itself is based on the infamous 1937 attack on a civilian town of the same name during the Spanish Civil War. General Franco (fascist leader of Spain) invited the Germans in to try out their new technique of mass aerial bombardment and terrorizing non-combatants. Its inclusion in the play seems to symbolize the inaction of Americans in the face of the Great Depression. "In Spain," faced with an economic system that kept most workers at a subsistence level, the proletariat rose up, regardless of the odds (pitchforks and shotguns against tanks and machine guns), and tried to defeat the fascists (read Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls for a more developed American [fictional] take on this). What was the American response to similar economic travails, a time when our "fingers [were being] pressed forcibly down on the fiery Braille alphabet of a dissolving economy" (1975)?

Other references come fast and furious: "Berchtesgaden" and "Chamberlain" (1993) are both references to WWII (for which the Spanish Civil War was a practice run -- as the audience would know), the former being a retreat for Hitler (a German version of Camp David), the latter being the British Prime Minister when Hitler was gobbling up the Europe -- and the rest of the world was reluctant to challenge him.

And a play that opens with explicit references to class strife, both local (in America) and global (Spain), and to war means that the audience needs to pay attention to the "p" word: politics. Not in the boring and fractious republican/democrat sense, but in the how people and governments interact sense. Consider, for example, that loaded term "democracy." Just what does it really mean? That's one of the questions posed by the play.

Finally, remember that this is, again as Tom (by the way, Tennessee Williams name was really Thomas . . . and he had a mother from the South . . . and a sister that was mentally unstable . . . and a drifter of a father) notes a "memory play" (1975). As a character in Ngugi Wa Thiong'o's brilliant novel Petals of Blood notes, "For what are recollections but fiction, products of a heated imagination?" (191). This heat, as we've seen throughout the semester, leads to gripping narratives that slake our thirst for sensation, philosophical ruminations that plumb the depths of our minds and souls, observations on the folly of humans and our relationships . . . in other words, the whole host of images and ideas that paint the canvas of life. We are, after all, artists in the gallery of our lives, right?

Sit back and enjoy the show.

- On the cover of his draft, Williams wrote "nobody, not even the rain, has such soft hands," which should sound familiar: it's from cummings' "somewhere i have never traveled, gladly beyond." Reread the poem, and figure out why Williams would have used this as an epigraph.

- In the Production Notes, Williams references a "new, plastic theatre." What does he mean by this?

- Tom and Tennessee both note that the play is "not realistic" (1583). How is this true? It seems realistic -- what makes it unrealistic? Is unrealistic the same as not realistic?

- Image on the screen seems borrowed from ____?

- If this is supposed to be an "unrealistic" play, is it convincing? Do the characters and actions seem convincing?

- When and where is the play set? Pay close attention to the setting: what is Williams "saying" about the Wingfields and, by extension, middle-class America?

- How do the "extra-literary accents" contribute (or interfere) with the play?

- Why is it valid to discuss the social background of this play?

- "Franco Triumphs" -- why is this detail included?

- Could this be a play about democracy? "Knowledge -- Zzzzp! Money -- Zzzzp! -- Power! That's the cycle democracy is built on!" (1621) is this true? Does it matter who is saying it? (cf. "I'm pretty clumsy with things")

- How does the play want us to view Laura? Are we to deride her "Hey you! Get on with your life!" or does the play suggest we should have empathy for her? How can you tell? Consider the following from the Production Notes: "When you look at a piece of delicately spun glass you think of two things: how beautiful it is and how easily it can be broken" (1581).

- What "kind of heroism" (1580) is in Amanda?

- What role does the father play in this play?

- How is

- Could this be a play about economics?

- What does the play suggest about war?

- "quiet desperation" Thoreau v. adventure. But is it as simple as inaction = bad, action/adventure = good? (1597) What is all the action he talks about relate to "all the world is waiting for bombardments!" (1660)

- Is Tom like other characters in the works we've read?

- Why the reference to the coffin trick?

- Amanda's worry: "What are we going to do, what is going to become of us, what is the future?" (1587). How does this line, after Amanda learns of Laura's absence from business school, capture Amanda's predicament?

- What distinctions does the play make between "instinct" v. civilization? And who is D. H. Lawrence and what's he doing in the play.

- Religion in the play? Annunciation: Angel Gabriel telling Mary (a virgin) she would conceive. Here, it's the gentleman caller. Trace out other strands of religion.

- Candelabrum burned -- why? And why end the play with candles?

- How does Amanda refer to Laura at the end of the play? (1628). What's changed to make her do so?

- What is the play suggesting about reality v. illusion? See the comments in the first section of the Production Notes for starters. Who lives in the reality and who lives in illusion? Consider Amanda's comment to Tom: "You live in a dream, you manufacture illusions!" (1628) -- while true, why is she so mad at Tom? And is he the only person in the play that lives in a dream?

- Follow the lighting in the play: how does enhance/contribute to the play's meaning/s?

- Why does Amanda wear her old dress when Jim comes? What effect does it have on the other characters?

- Is this a tragedy? Who's the hero? What's the flaw? What's the crisis?

- Why the dual times of the action? Why have a narrator in the present recalling events in his past?

- What descriptions, by both characters and the author (stage directions, etc.), suggest the social and economic position of the Wingfields?

- What does the "Pardise Dance Hall" symbolize -- for both good and ill?

- Lester Beaurline writes that " Jim finally impresses us as a dehumanized figure, an unromantic voice of power and cliché; [ . . . .] he embodies Tom's 'celotex interior'." Do you agree with this interpretation? Why or why not?

- Back to the beginning: how does Jim resemble Richard Hunter, the protagonist of Horatio Alger's Ragged Dick?

- In the Production Notes, Williams references a "new, plastic theatre." What does he mean by this?

- How does the play want us to view Laura? Are we to deride her "Hey you! Get on with your life!" or does the play suggest we should have empathy for her? How can you tell? Consider, for example, the Tom's remark to Amanda: "in the eyes of others -- strangers -- she's terribly shy and lives in a world of her own and those things make her seem a little peculiar to people outside the house" (1604). How are we, the audience, "strangers"?

- Is this a tragedy? Who's the hero? What's the flaw? What's the crisis?

- Why the dual times of the action? Why have a narrator in the present recalling events in his past? How does this effect our understanding of the play and the characters?

Online exhibition Becoming Tennessee Williams at the Harry Ransom Center, Univeristy of Texas at Austin.

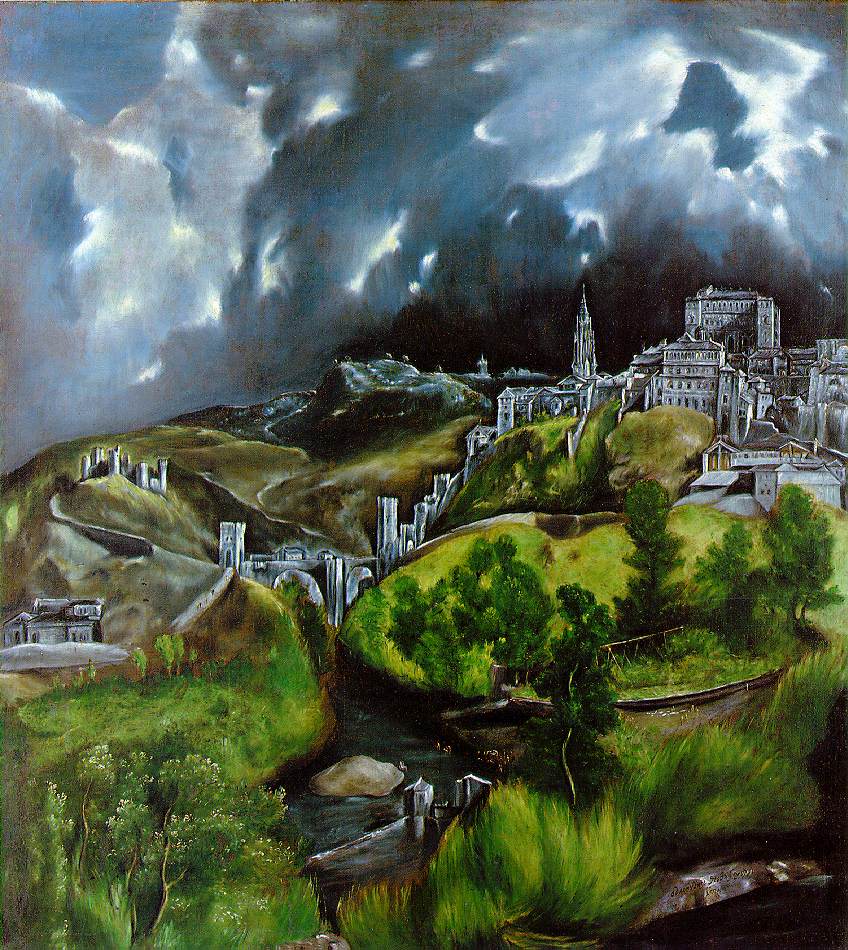

Williams mentions El Greco in the play: below find a few of his signature paintings.

Click to enlarge.

|

The Annunciation

|

View of Toledo |

St. John the Baptist |

Quotes from Critics

Work Cited

Beaurline, Lester A. " The Glass Menagerie: From Story to Play." Modern Drama. 8.2 (Sept. 1965): 142-149. Rpt. in Short Story Criticism. Ed. Thomas J. Schoenberg and Lawrence J. Trudeau. Vol. 81. Detroit: Gale, 2005. 142-149. Literature Resource Center. Gale. Ocean County College Library. 22 Apr. 2009.

Wa Thiong'o, Ngugi. Petals of Blood . New York: Penguin, 1977.

Williams, Tennessee. The Glass Menagerie. Literature: An Introduction to Fiction, Poetry, and Drama. Ed. X. J. Kennedy and Dana Gioia. New York: Longman, 1999. 1972-2022.

Image Credits

Ad for The Glass Menagerie . New York Times. 18 March 1945: X2. Proquest Historical Newspapers.

Online. Ocean County College Library. 14 October 2004.

Guernica. http://web.uvic.ca/akeller/pw401/resources/rf_image_optimze/guernica_large.jpg

© David Bordelon 2009