Lesson Plans

Course Links

Lesson Plans

Course

Documents Links

Secondary Sources

Quick Links

Library

Links

Citing

Sources

Langston

Hughes and Countee Cullen

1920s-1940s

|

|

|

Terms | Life | Times | Class Discussion | Group Questions | Links | Pictures | Quotes from Critics

Terms to Know

Harlem Renaissance:

occurred during the 1920s, a result of the confluence of black

American

writers and artists in a district which was already fashionable

among

the white smart set as the music-and-entertainment capital of New

York.

The early years of the century had seen the publication of works

such

as W. E. B. DuBois's The Souls of Black Folk and Booker T.

Washington's

Up From Slavery, indicating the future role of black people in

America.

In 1925, Alain Locke, a professor at Howard University, brought

together a collection of short stories, poems, and prose by divers

hands, under the title The New Negro. As the abstraction was held

to

characterize the "spiritual Coming of Age" of the black race, so

the

volume itself could be seen as a mark of its cultural maturity.

Major figures in the Harlem Renaissance were Langston Hughes, Arna Bontemps, James Weldon Johnson, Nella Larsen, Countee Cullen, Claude McKay, Jean Toomer, and Zora Neale Hurston, many of whom treated the themes of black life in a way that felt modern, while borrowing elements from the folk literature of black tradition. Visual artists of the Renaissance, including Aaron Douglas and William H. Johnson, incorporated African and primitive motifs into their work. Among the magazines founded at the time which devoted themselves to "Negro studies" were Crisis (edited by DuBois), Opportunity, and the Messenger.

These magazines were not exclusively literary, but the significance of the Harlem Renaissance did not lie solely in its literary impact. Although much that was produced from Harlem in the 1920s is of greater historical than artistic importance, the Renaissance made white America aware for the first time of the modern art of a people it had not long before kept in slavery.

For an account of this development see Harlem Renaissance, by Nathan Irvin Huggins (New York, 1971). When Harlem Was in Vogue, by David Levering Lewis (New York, 1981) is a study of broader scope, with less emphasis on the literary life of the 1920s.

Campbell, James. "Harlem Renaissance, The." The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-Century Poetry in English. Ed. Ian Hamilton. Oxford University Press, 1996. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Ocean County College. 14 April 2009.

For a more detailed definition, read the entry in the Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature.

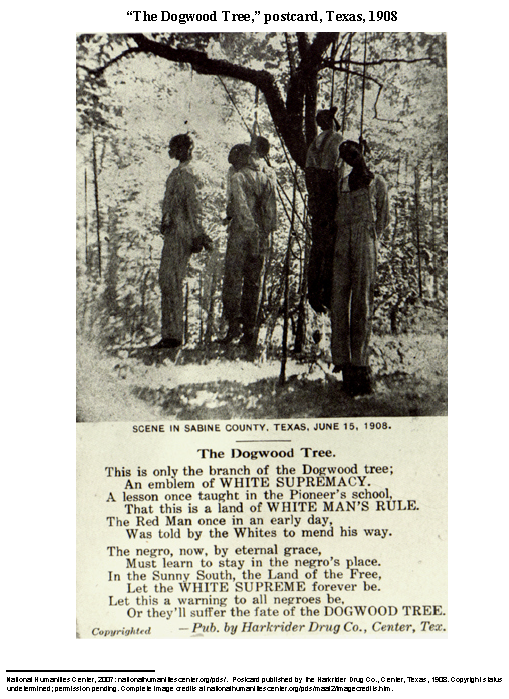

Lynching: a form of illegal execution, usually of a person accused of a crime or some type of deviant behavior. Historically, most lynching victims in the United States have been African-American males. However, women, native-born white males, and members of other minority groups (including European immigrants, Chinese, and Hispanics), were also lynched, though in much smaller numbers. Although lynchings are often equated with hanging, other methods that have been used include shooting, burning, and drowning, sometimes followed by the mutilation and/or public display of the corpse. Some lynchings were carried out by large mobs, while others involved groups of only three or four members. White supremacist or nativist groups like the Ku Klux Klan perpetrated some lynchings, but the informal and spontaneous organization of citizens into lynch mobs was more common. Most lynch victims had been accused, but not convicted, of such serious crimes as murder, assault, or rape. Other victims were killed because of transgressions of racial codes such as insulting a white person or using inflammatory language.

Follow link for remainder of essay

Stewart E. Tolnay , E.M. Beck. "Lynching." The Oxford Companion to United States History. Paul S. Boyer, ed. Oxford University Press, 2001. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Ocean County College. 16 April 2009.

And see the Without Sanctuary website for a flash movie of lynching postcards.

Uncle Tom: Although Harriet Beecher Stowe 's extremely successful 1852 abolitionist novel Uncle Tom's Cabin was the original source for the Uncle Tom idiom, its meaning is best understood through an examination of the numerous stage shows loosely based on the best-selling book. Theatrical entrepreneurs who did not share Stowe's antislavery zeal took great liberties with the novel's protagonist. Uncle Toms of the stage were usually depicted as thoroughly subservient individuals who willingly betrayed their black brethren in order to please their white masters. As a result, the Uncle Tom label is assigned to individuals who sabotage other blacks in order to further their own advancement. Known popularly as Tom shows, stage productions of Uncle Tom's Cabin were a mainstay of American theater well into the twentieth century. Uncle Tom became a trope, a figure of speech used to refer to fawning, selfish black men. Thus Uncle Tom's ubiquitousness had a definitive impact on mainstream society's assumptions about actual black men.

By the turn of the century, a curious battle developed between the purveyors of popular culture, who continued to promote Uncle Tom, and African American writers and social critics eager to bury the demeaning image. Thus filmmakers made several films similar to the stage shows. Even the Siam-based musical The King and I (1951) contains an ode to Uncle Tom's Cabin. For a collection of short stories on the black experience in the South, Richard Wright used the title Uncle Tom's Children (1938). Ralph Ellison noted that a Tom show was one of the original impetuses for his novel Invisible Man (1952). Ishmael Reed manipulated characters' names for his novel Mumbo Jumbo (1972), and Robert Alexander wrote a provocative play entitled I Ain't Yo Uncle: The New Jack Revisionist Uncle Tom's Cabin (performed in Hartford, 1995). Nonetheless, the negative associations of the name remain consistent. For example, the Uncle Tom label is often applied to staunchly conservative African American Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. It seems likely that this pejorative label will remain in the American vernacular.

Patricia A. Turner. " Uncle Tom." The Concise Oxford Companion to African American Literature. Ed. William L. Andrews, Frances Smith Foster, and Trudier Harris. Oxford University Press, 2001. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Ocean County College. 16 April 2009.

River Jordan: The Egyptian river the Israelites had to cross to to be free from slavery -- the river crossed to reach the promised land. It can also be considered a movement from life to death (temporal world to heaven), and conversely, death to life (temporal world to heaven -- and yes, the repetition is intentional).

Cotton Club: The Harlem cabaret is perhaps the most fabled intersection of the jazz age and the Harlem Renaissance, and no cabaret was more fabled than the Cotton Club -- the "aristocrat of Harlem -- at the northeast corner of Lenox Avenue and 142 Street: Between its opening in September 1923 and its relocation downtown in February 1936, the Cotton Club would boost the early careers of Edith Wilson, Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, Aida Ward, Adelaide Hall, Earl "Snakehips" Tucker, Mantan Moreland, Ethel Waters, Lena Horne, the Nicholas Brothers, and the bands of Duke Ellington (in 1927-1931 and 1933), Cab Calloway (in 1930-1933), and Jimmie Lunceford (in 1934-1936). As famous for its exclusionary racial policies as for its fast-stepping revues, the Cotton Club embodied many of the contradictions of the popular Harlem Renaissance; its cultural meaning was shaped by the combined forces of Prohibition economics, postwar trends in musical theater, black performance traditions and innovations, white patronage, and the mass media. [. . . .] Joseph Urban, Florenz Ziegfeld's celebrated set and costume designer, redesigned the interior in what [Barry] Singer describes as "a brazen riot of African jungle motifs, Southern stereotypology, and lurid eroticism" (1992, 100) [. . . . ]

A key innovation in creating the Cotton Club's exclusive atmosphere was Madden's seemingly paradoxical introduction of a strict color line into the heart of Harlem. In establishing a whites-only policy regarding customers, Madden was following the practice at Connie's Inn, a rival Harlem club favored by moneyed whites. At the Cotton Club, the concept was extended to the division of labor, creating a strict divide between the whites who ran the club and produced, wrote, and choreographed its shows, and the blacks who cooked, waited and bussed tables, and entertained. Women in the chorus line faced their own color bar; they were essentially conceived as part of the club's decor, and they were expected to be "tall, tan, and terrific": at least 5 feet 6 inches, no darker than a light olive tone, and under twenty-one.

From The Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance.

The Life

See the introductions in the textbook and the

concise entries on Hughes

and Cullen at the Modern American Poets site.

To get an understanding of Hughes' role in promoting a black aesthetic, review the short excerpt from "The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain," in our textbook (1512) and the full essay here.

2015 New Yorker essay on Hughes -- insightfully captures many of the contradictions in his work and life.

The Times

Lynching,

racism, passing. These are all components of being black in

America in

the early 20th century. But there was also a sense of resurgence

and

optimism. This sense of change, of breaking established traditions

is

one aspect that makes the Harlem Renaissance part of the modernist

movement.

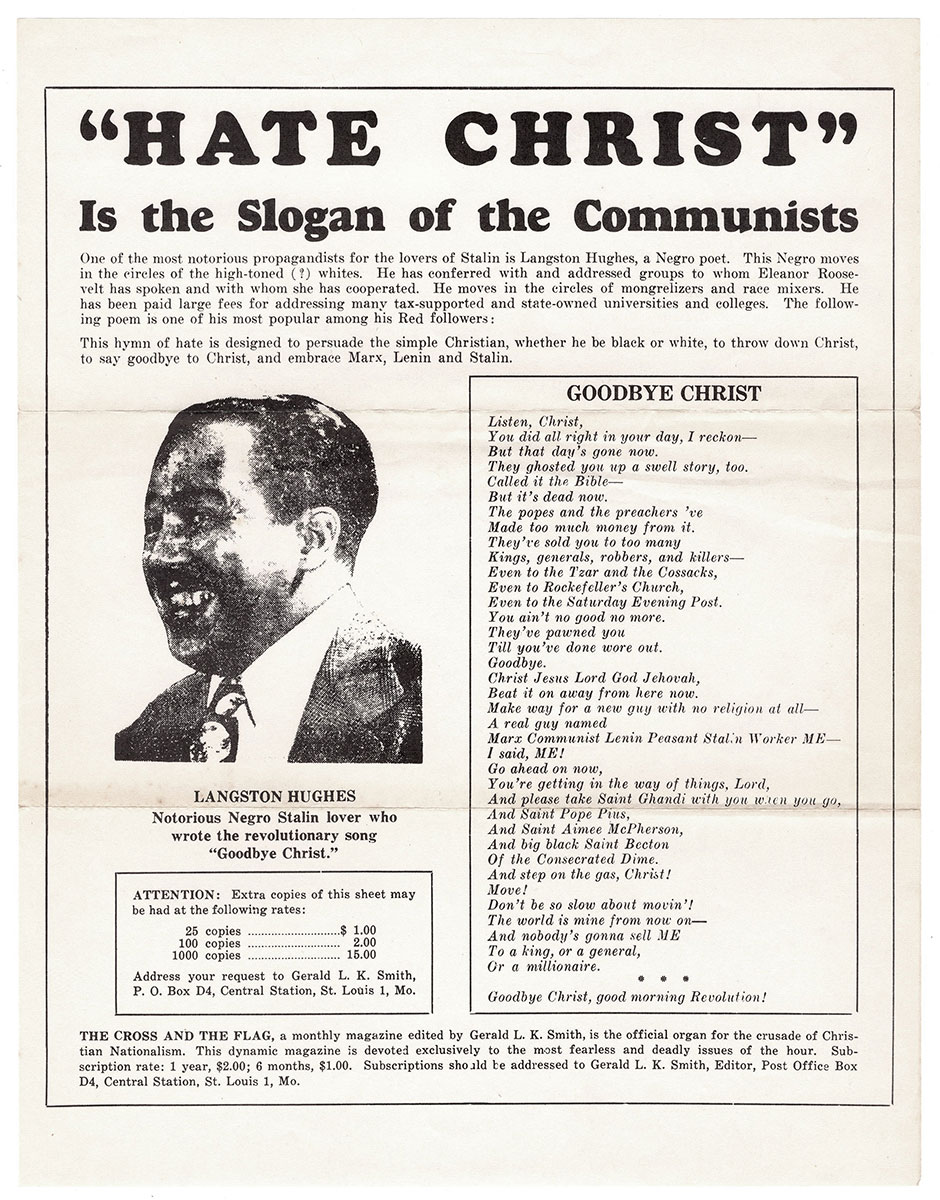

For an idea of the animus Hughes faced, consider this excerpt published byThe Cross and the Flag

Perhaps a reason he wrote this poem, can be found in an earlier and also explicitly religious poem -- which comes with an illustrative photograph.

Consider, as well, his essay "In the Death House with the Scottsboro Boys"

The FBI and the Harlem Renaissance. It would be amusing if it wasn't sad.

And the connection to politics? Consider the views of a Mississippi politician, circa 1920s.

In 1923 former senator James K. Vardaman of Mississippi, popularly known as 'the Great White Chief' (his campaign slogan was "A vote for Vardaman is a vote for white supremacy"), published his own newspaper, Vardaman's Weekly, in effect an early version of social media. That May Vardaman's Weekly proclaimed its editor a man who had fought the battle to make America "pure, free and safe" That may sound unobjectionable, but in practice, the battle to make America pure had included Vardaman's notorious declaration, "If it is necessary every Negro in the state will be lynched in order to maintain white supremacy" (qtd. in Churchwell 143).

From Barbara Churchwell's Behold America.

Hughes

Hughes exploration of popular music is part of a larger black aesthetic first promulgated by W. E. B. Dubois in The Souls of Black Folk (1903) which ends with an evocation of black folk music as the song of America:

Little of beauty has America given the world save the rude grandeur God himself stamped on her bosom; the human spirit in this new world has expressed itself in vigor and ingenuity rather than in beauty. And so by fateful chance the Negro folk-song--the rhythmic cry of the slave--stands to-day not simply as the sole American music, but as the most beautiful expression of human experience born this side the seas. It has been neglected, it has been, and is, half despised, and above all it has been persistently mistaken and misunderstood; but notwithstanding, it still remains as the singular spiritual heritage of the nation and the greatest gift of the Negro people. (251)

This explains, in part, Hughes' embrace and emphasis on the Blues, spirituals, and other forms of black folk music.

And Hughes was strongly influenced by the voice and aims of Walt Whitman poetry.

"The Negro Speaks of Rivers" (2027)

- Why would a negro speak of rivers? What role do rivers play in African American culture?

- Why the Euphrates? What could this connote? Why each of these particular rivers?

- Adrian Oktenberg argues that " Every element of the poem combines to suggest that when the Negro speaks of rivers it is with the accumulated wisdom of a sage. The function of a sage is to impart the sometimes secret but long accumulated history of a people to its younger members so that they might make the lessons of the past active in the future." How do the sound of the words contribute to this message?

- Look at the words which connote color: why choose these words?

- Why repeat "ancient" and why the emphasis on time/history?

"I, Too" (2028)

- What kind of singing does the poem refer to?

- Why the single word lines "Tomorrow" and "Then"?

- Why shift from "sing" to "am" at the end of the poem?

"The Weary Blues" (2029)

- Obvious, but necessary: why the blues?

- Why "Weary" and not "Tired"?

- How does the second line answer the first line?

- Why the repetition of "He did a lazy sway . . . " (note -- remember not everything in a poem is done for meaning).

- How does Hughes inject music into this poem?

- Why is the piano player singing the lines? What does this reveal about him?

- Lenox Avenue was the location of the Cotton Club (see Terms to Know above for what this signifies). How might this explain the piano player's emotions and thus the poem (consider, especially, the last line)?

- For a more contemporary view of black musicians in America, see this site describing the 1959 beating and arrest of Miles Davis by the NYPD. http://milesdavis.wordpress.com/2008/07/30/the-miles-davis-movie-filming-the-birdland-attack/

"Democracy" (title Freedom in our textbook)

"Theme for English B" (2038) Vol. D

- Consider the "like" part of this poem -- what is he trying to convey?

Countee Cullen (circa 1920s)

"Yet Do I Marvel" (2061)

- Why this form and not open verse?

- Fred Fretow argues that " The sonnet seems to many readers and critics no more than the lament of a defeated soul, a complaint by a man unable to resolve the dilemma of being black and a poet. A reconsideration of the poem's structure and logic reveals that Cullen actually expresses the resolution of a paradox, rather than bemoaning his fate." How is this true?

"Uncle Jim" (2065)

"For a Lady I Know"

- OED cherub, focusing particularly on the end of the initial paragraph. Why is this the perfect word for this poem?

- How does Hughes' poetry represent the modernist aesthetic? Use the Major Literary Movements Review on the Modernism page for a listing of the major tenets.

- On "The Negro Speaks of Rivers:" Adrian Oktenberg argues that " Every element of the poem combines to suggest that when the Negro speaks of rivers it is with the accumulated wisdom of a sage. The function of a sage is to impart the sometimes secret but long accumulated history of a people to its younger members so that they might make the lessons of the past active in the future." How do the sound of the words contribute to this message?

- Connect the follow quote from W. E. B. Dubois' The

Souls of Black Folk with Hughes' work:

Little of beauty has America given the world save the rude grandeur God himself stamped on her bosom; the human spirit in this new world has expressed itself in vigor and ingenuity rather than in beauty. And so by fateful chance the Negro folk-song--the rhythmic cry of the slave--stands to-day not simply as the sole American music, but as the most beautiful expression of human experience born this side the seas. It has been neglected, it has been, and is, half despised, and above all it has been persistently mistaken and misunderstood; but notwithstanding, it still remains as the singular spiritual heritage of the nation and the greatest gift of the Negro people. (251)

- Lenox Avenue was the location of the Cotton Club (see Terms to Know above for what this signifies). How might this explain the piano player's emotions and thus the poem (consider, especially, the last line)?

- For Cullen's "For a Lady I Know," OED cherub, focusing particularly on the end of the initial paragraph. Why is this the perfect word for this poem?

Links

While a bit awkward to navigate, the Harlem

Renaissance

by John Carroll University is worth a look.

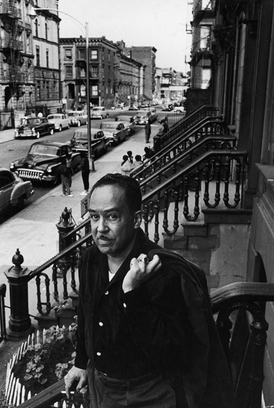

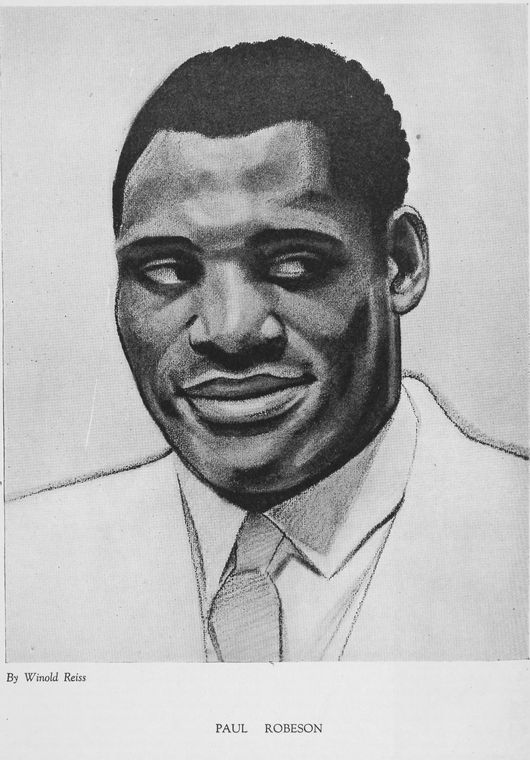

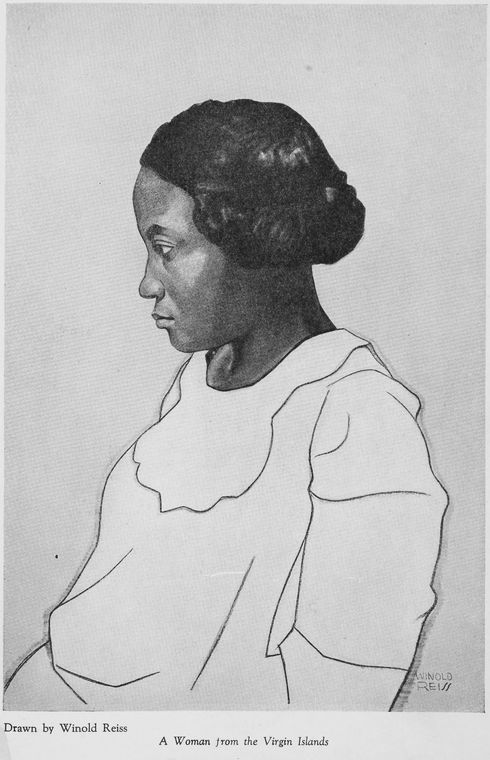

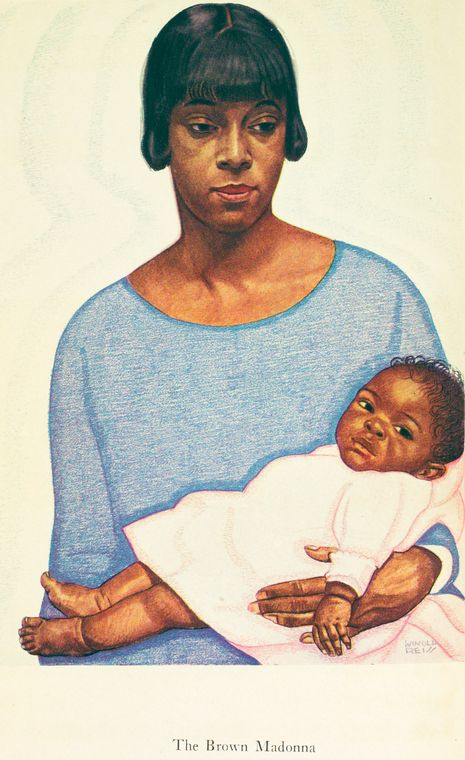

Pictures, Pictures,

Pictures

Below

you'll find images of work by Winold Reiss and Aaron Douglas, two

visual artists that Hughes upheld as people who weren't afraid to

show

blacks as having their own beauty.

Click to enlarge images.

|

Reinold Weiss All Weiss images from NYPL Digital Gallery |

Reinold Weiss |

Reinold Weiss |

Reinold Weiss |

|

Aaron Douglas |

Aaron Douglas (1934) http://www.professorlewis.com/myblog/wp-content/uploads/2008/12/7aspects-of-negro-life_slaveryreconorg.jpg |

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/535576580673266369/?autologin=true

Quotes from Critics

Langston Hughes "The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain" 23 June 1926 The Nation.

"But, to my mind, it is the duty of the younger Negro artist, if he accepts any duties at all from outsiders, to change through the force of his art that old whispering 'I want to be white,' hidden in the aspirations of his people, to 'Why should I want to be white? I am a Negro--and beautiful!'"

© David Bordelon 2009