Lesson Plans

Course Links

Lesson Plans

Course Documents Links

Secondary Sources

Quick Links

Library Links

Citing Sources

"Life in the Iron Mills"

Rebecca Harding Davis

Atlantic Monthly 1861

Terms | Life | Times | Class Discussion | Group Questions | Links | Pictures

Image from http://www.lehigh.edu/~dek7/SSAWW/photoDavis.htm

Terms to Know

Darwinism : In business, this amounted to a belief in unfettered capitalism. It was a doctrine that took the law of the jungle (only the strong survive -- popularized by Darwin and Herbert Spencer), and applied it to the economic sphere. Thus any technique that allowed a business to prosper -- price-fixing, price gouging, monopolistic practices, exploiting your work force by (literally) working them to death -- was deemed proper and even beneficent because it was what nature intended. Indeed, any motion to go against the course of nature and, gasp, treat your workers or competition with favor was strongly rejected because it would upset the natural balance

Reform: The nineteenth century was an era of optimism, when people thought society's problems and life in general could be changed; and if something is changed for the better, it's called "reformed" (though one person's reformation is another person's heresy). The literary historian David Reynolds believes that the antebellum period united "piety" with "moralism," leading to two broad categories of reformer: religious and rationalists (57). The religious reformers brought their evangelical zeal and intolerance to the fore, eventually leading to such large scale changes as prohibition. The rationalists, "based mainly in the Northeast, included Unitarians, freethinkers, and Quakers who promoted education and rational self-improvement" (Reynolds 57). Note that while Unitarians and Quakers are religions, they're not included in the religious reformer category because they wore their faith lightly: for them, change was not a religious imperative, but a more humanitarian ideal.

And consider the following from Jacob Abbott Cram in 1860: Fiction "now claims the ability and the right to discuss the great problems of social reform which are agitating society, and thus increase still further the sphere of its practical usefulness." (Abbott 72)

Realism: A literary movement that focuses on the matter of fact, the every day life, and attempts to report it objectively. While it purported to ignore morality, simply illustrating reality has a way of instigating changes.

Two criticisms of realism include 1) it generally focused on middle to upper class life and thus didn't represent "real life." And 2) any attempt at objectivity is doomed because an artist will always be limited by their subjectivity.

From the period, consider the following:

Richardson, Charles F. "The Moral Purpose of the Later American Novel." Andover Review. April 1885: 312-325. Print.

"What, then, is modern American realism? . . . . realism stands without, not within; describes without evidence of personal sympathy; seldom indulges in exclamations, reflections, or sermons based upon the narratives which it offers; leaves the reader to draw his own conclusions concerning right and wrong; describes by implication, or minute rather than large characterization; is fond of petty details; devotes itself chiefly to quiet people of the `upper' or middling classes; and extensively patronizes Atlantic steamships and Continental [316] railways. It has been most conspicuous, though not the most important, development of later American literature, and its leader is Mr. Henry James" (Richardson 315-316),

For additional information, see the "Realism" paragraph entry in the Oxford Companion to American Literature. For a richer discussion, see the Naturalism and Realism essay from The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature.

Naturalism: A literary movement prevalent in later nineteenth century America that, as Lars Ahnebrink writes, "a manner and method of composition by which the author portrays life as it is in accordance with the philosophic theory of determinism [. . . .] To a naturalist man can be explained in terms of the forces, usually heredity and environment, which operate upon him" (vi). Ahnebrink writes that naturalist writers exhibit a "post-Darwinian belief that man was fundamentally an animal; his actions therefore depended essentially upon physiological phenomena" (214).

For additional information, see the "Naturalism" paragraph entry in the Oxford Companion to American Literature. For a richer discussion, see the Naturalism and Realism essay from The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature.

Quakerism: A gentler, milder form of Calvinism (whose more assertive form, Puritanism, many of you are familiar with). It believes that the central message of Christianity is doing good for others and as such it is committed to improving the social welfare of all through good works and education. This does not mean that Davis accepts the empty pieties of established religion: as she explains in her memoir Bits of Gossip: "unfortunately, he [the 1840's man] mistook dogmas for religion." (100) What she believes in, is the Christian belief of helping your fellow man, best exemplified by the Quakers.

Sensationalism: In general, this refers to exaggerated actions or descriptions which transgress the bounds of accepted behavior. Sensational literature is an attempt to render such actions in prose and specifically refers to fiction and non-fiction which revels in detailed and graphic descriptions of crime, violence, or sexual matters, usually presented as "realistic" portraits of the events described. By combining graphic depiction and realism, this type of writing accentuates the horror or disgust of a given scene or series of incidents, and both shocks and attracts readers by appealing to the salacious or voyeuristic in human nature.

Sentimentality/Sentimental literature: Just as crime and violence can draw readers, so can scenes dealing with sadness. This kind of literature exults in scenes depicting strong emotions, such as deathbed vignettes (particularly with children), children being abused or separated from their parents, and scenes of characters overcome with emotions and/or crying. These are meant to evoke a curious mix of pain and pleasure. Consider the following definition of sadness after the death of a loved one from a popular 1854 gift-book. After describing the initial realization of sadness as "gloomy and solemn as the death-knell," it offers an interesting qualification: "Still it is a delicious sort of sorrow; and like a cloud dimming the sunshine of the river, although causing a momentary shade of gloom, it enhances the beauty of returning brightness" ( Scrap-Book 353). Pathos, in this case a remembrance of things past, has the power to conjure up both darkness and light.

Consider the following definition as well: "As a child of philosophical idealism, Victorian sentimentality defended the vision of the ideal against the claim that the universe and human history are governed by mechanical, or rational, or deterministic, or pragmatic forces; that we cannot maintain metaphysical or religious ideals; that all human nature is flawed; and that literature should not falsify life by depicting ideal characters and happy endings. . . . Victorian sentimentality, I suggest, was late and occasionally shrill stage in a vigorous rear-guard action to defend human nature from further devaluation" (Kaplan 6)

For a more detailed look at this literary genre, see this essay on sentimental literature in the Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature.

The American Dream: Work hard, live right, and you will prosper in this great land of ours.

Marxist Criticism : A marxist critic takes ideas of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (circa 1848) -- that the basis of much (all?) human social interaction is economic -- and applies it to literature. Thus, a marxist critic explores the relationships between worker (proletariat) and boss, the upper and lower classes, the haves and the have nots. Marxism assumes that these relationships are all pervasive, overcoming even a strong-willed person; thus workers, regardless of their intellect or emotion, become subservient to the machine, or subservient to the oppressor. The "bright" side of this theory is class revolt: Marx writes that the lower classes will eventually "rise up" and throw off the chains of their oppression. Marx also famously described religion as "the opiate of the masses" -- a means of social control. In literature, Marxist criticism is often employed to explain the dynamic in class differences, the tensions between worker and employer, and the debilitating effects of poverty or wage-slavery.

The Life

According to Lawrence Jones of Great Writers of the English Language, "She lived for her first thirty-two years the proper life of a middle-class spinster in the frontier industrial town of Wheeling, West Virginia, out of touch with literary circles, restricted in her social contacts. Yet she wrought out of this limited life a coherent theory of literary realism."

Davis was born in Washington, Pennsylvania, in June of 1831. Educational opportunities were scarce for young women of that era, so Davis set about educating herself. From an early age, she enjoyed reading and writing. However, she was limited by her rural environment, and thus, wrote stories mainly for herself. During these early years, literature was evolving both in America and abroad. The Victorian novel had been in vogue for quite some time, but it was during the 1830s that a literary shift began. Born out of a reaction to the romanticism of the Victorian era, in addition to the newly industrialized work force, more and more writers began employing realism in their work. Charles Dickens's novels marked a new wave in literature, employing both realism and social criticism to comment on the evils present in nineteenth century America.

Bio quoted from Contemporary Authors Online, Thomson Gale, 2005.

The Times

Published in 1861, though set in the 1840s, the approaching Civil War provides the central background to the story. Pay attention to references to slaves and slavery and to the essay that follows the story itself.

Davis' negative view of determinism stems from her cynical view of the "American Dream." In his book Intellectual Life in America: A History, Lewis Perry calls mid-nineteenth century culture a "melange of optimism and anxiety....All barriers to growth and achievement seemed to crumble. It was possible to dream of expressing one's deepest genius, of gaining fame and wealth, of furnishing leadership to the new age" (207). In The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in the Gilded Age, Alan Trachtenberg notes that "many Americans before the Civil War had believed that industrial technology and the factory system would serve as historic instruments of republican values, diffusing civic virtue and enlightenment along with material wealth" (38). This enthusiasm for the supposedly limitless opportunity of Americans in this period, is an extension of the view suggested in the 1830's by Tocqueville. In Democracy in America he writes of America 's glorification of the working man: "Labor is held by the whole community to be an honorable necessity of man's condition....If all are not alike, all at least have one feature in common. No profession exists in which men do not work for money; and the remuneration that is common to them all give them all an air of resemblance." (v.2 153)

While this is a romantic view of American society, Tocqueville characteristically tempers his enthusiasm with an acute observation of the wealthy in America :

They are not, indeed, callous to the sufferings of the poor; but they cannot feel those miseries as acutely as if they were themselves partakers of them. Provided that the people appear to submit to their lot, the rulers are satisfied and demand nothing further from the government. An aristocracy is more intent upon the means of maintaining than of improving its condition.

(v.1 215)

The historian Russell Blaine Nye reports that

The attitude toward poverty in the forties and fifties was ambivalent. Some people were poor, it was assumed, because they were morally incapable of living a better life; they were, said one investigator, `content to live in filth and disorder with a bare subsistence.' . . . . For the most part, poverty was considered a personal rather than a social responsibility, to be cured by reforming the person himself and rewarding him for ridding himself of those habits that made him poor.

Poor relief and charity work, therefore (at least until the sixties), consisted chiefly of providing moral instruction for the poor, with some direct assistance to alleviate present suffering." (Nye Society 45)

From The Almighty Dollar! or The Brilliant Exploits of a Killer, a Romance of Old Quakerdelphia . Philadelphia. 1847. Rpt. in Notions of the Americans 1820-1860. Ed. David Grimsted. New York : George Braziller, 1970. 245-259. Print.

"aristocrats." From their "Constitution:" "Society is so framed, and the DOLLAR has become such a mighty engine, and those who have wealth have power, and those who have poser will be sure to abuse it . . . . Therefore, it is apparent that the rich want a signal estrangement from the people, and WE, the people, swear an eternal estrangement, a deadly enmity, a war of extermination against the aristocrats, the plunder and burning of their property , and all the mischief that can be concocted and executed against those overbearing and self-styled demigods" (Almighty 251).

- We'll be focusing on religion, politics, realism, slavery, reform, class, wealth, role of art/artist, American Dream, metaphor/symbolism, narrative intrusion, exaggeration, sensationalism, sentimentality

- How many times do references to money occur?

- Recourse to politics?

- Recourse to religion? What does the preacher believe is the problem with the poor? What symbolism do we see right after Hugh leaves the church?

- Why do we find out what happened to Hugh via Dr. May ?

- Interesting connection b/t Hugh cutting the korl for freedom of a sort, and then cutting at the iron bars -- though the latter is to turn the tin into a knife

- This is one of the essential questions of the novel: "was there right and wrong for such as he? What was right?" and "What made the difference between them";

- What does the Korl Woman symbolize?

- What is marxism again? How would a Marxist read this story

Style

- Framing -- narrator addresses herself at the beginning and end of story

- Narrator: Directly addresses the reader several times "you laugh at it?" 48 "I want you to come down and look at this Wolfe"; why?. What's the tone she uses when speaking directly to the reader? Why does she adopt this tone? Is it effective?

- symbolism -- Much like Hawthorne, a writer who strongly influenced her work, she was drawn to darkness and light as symbols ("in the flickering nebulous crimson, God has set the promise of the dawn") Note that the light that comes to him at the end is moonlight (71) -- a light in darkness.

- What do you make of the end? Does the ending with Deborah seem true to the intention of the story?

- Tug b/t romanticism and realism here. The romanticism exhibits itself in the sensationalized portrayal, and the exhortions to the reader, subjective voice of the narrator. Realism comes from the subject matter, and the outcome for Hugh.

- Why is he a called "Molly Wolfe" (48) What does this do to our understanding of him as a character?

- Is Deborah's hunchback too much? Does it weaken the story by its sensationalism?

- Deborah always hangs back and waits -- why?

Naturalism

Lars Ahnebrink defines naturalism as:

a manner and method of composition by which the author portrays life as it is in accordance with the philosophic theory of determinism....To a naturalist man can be explained in terms of the forces, usually heredity and environment, which operate upon him. (vi)

He adds that naturalist writers exhibit a "post-Darwinian belief that man was fundamentally an animal; his actions therefore depended essentially upon physiological phenomena" (214) As an animal, man can be divided into sub-species, and separated according to class and environment. Darwin 's philosophy can also be interpreted as an excuse to subjugate man into upper and lower class categories (cf. Social Darwinism -- law of the jungle/survival of the fittest).

- Can you find the features of naturalism noted by Ahnebrink in this novel?

Class

In his travel book/political treatise on America , Democracy in America (1848), the french writer and political theorist Tocqueville remarked, on the wealthy in America , that

They are not, indeed, callous to the sufferings of the poor; but they cannot feel those miseries as acutely as if they were themselves partakers of them. Provided that the people appear to submit to their lot, the rulers are satisfied and demand nothing further from the government. An aristocracy is more intent upon the means of maintaining than of improving its condition. (v.1 215)

- Do you find this true in Life ?

Reform movement in America

In antebellum America , the idea of reform was very popular. As Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote in a letter to the British writer and political theorist Thomas Carlyle in 1840, "We are all a little mad here, with numberless projects of social reform. Not a reading man but has the draft of a new community in his pocket."

And what united various reformers, argues David Reynolds, " was a conscious impulse to 'tear away veils' or 'lift up masks' in an effort to reveal hidden corruption. To antebellum reformers (particularly the increasingly prominent Subversive reformers), authority figures such as urban aristocrats, wealthy churchgoers, Catholic priest, landlords, bankers, and so forth were 'whited sepulchres' whose inner rottenness could be revealed only through what I term unmasking images: violent, often sensational language designed to strip hypocrites of their sanctified cloaks and bring to light the horridness within" (Reynolds 86).

- Do you see this urge to "tear away veils" in the novel?

"In the eyes of many reformers, America itself was a nation that could be best described through contradiction or paradox: it was a republic that permitted slavery: it was a democracy that was witnessing widening class divisions; it was a land of virgin wilderness but also festering cities; it was a nation of Christians who tolerated the most unChristian practices" (Reynolds 86).

- Okay, this one might be too easy: do you see this contradiction in the novel?

Remember to use quotes from the story to support your answers to these questions

- Why use korl? Why not work with clay or sketching? And why a korl woman? Why not a korl man?

- What is the "American Dream"? What does the experience of Wolfe, and the attitudes of Kirby, Mitchell and Dr. May, suggest about the ideal of "the American Dream"?

- What role does the press play in the story? The last words directed at Wolfe are "Be quiet." Why?

- Why have Wolfe commit suicide? How does this shape our reading of his character and of Davis's conception of the culture he lived in?

- How is this a story about slavery?

- What does this story suggest about religion, a belief that lay at the core of most American's identities.

- Why do you think the editor deleted the section included in your syllabus? Why did Davis restore when the story was reprinted in book form with other short stories she had written?

- Which literary term best describes this story: realism or naturalism? Why?

Rebecca Harding Davis: Complete Works

American Values Survey 2011: Pew Research

In this case, links to contemporary America

And what about helping the poor?

Lee Iacocca, former CEO of Chrysler (who loves to talk about personal responsibility but conveniently forgets that without a US government loan his car company would have gone bankrupt) speaking at a press conference in Buenos Aires in 1993:

"The problem of unemployment is a tough one. Today we can make twice as many cars with the same number of people. When they talk about improving people's educational levels as a solution to the problem of unemployment, I'm always bothered by the memory of what happened in Germany . Education was put forward as the solution to unemployment, and the result was hundreds of thousands of frustrated professionals who then turned to socialism and rebellion. It's not easy for me to admit, but I wonder if it wouldn't be better for the unemployed to smarten up and go straight to McDonald's to find a job" (qtd. in Galeano 34)

Galeano, Eduardo. "Economics for Children." The Nation. 1 January 2001: 34. Print.

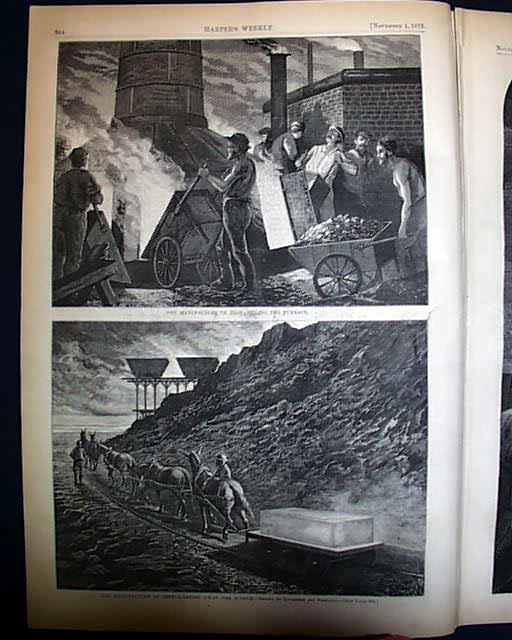

Pictures, Pictures, Pictures

From an article titled "The Manufacture of Iron" Harper's Weekly. 1 November 1873.

From http://images.rarenewspapers.com/ebayimgs/2.33.2007/image014.jpg

Works Cited

Ahnebrink, Lars. The Beginnings of Naturalism in American Fiction; A Study of the Works of Hamlin

Garland, Stephen Crane, and Frank Norris, with Special Reference to Some European

Influences, 1891-1903. New York, Russell & Russell, 1961. Print.

Cram, Jacob Abbott. "The Attempts of Modern Writers of Fiction to Inculcate Doctrines

of Philantropy, and Promote Schemes of Social Reform." University Quarterly July 1860:

70-83. Print.

Reynolds, David S. Beneath the American Renaissance:The Subversive Imagination in the Age of

Emerson and Melville. Harvard University Press: 1989. Print.

The Scrap-Book: Consisting of Tales and Anecdotes, Biographical, Historical, Patriotic, Moral,

Religious, and Sentimental Pieces, in Prose and Poetry. Comp. William Fields. 2nd Ed.

Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co., 1854. Print.

© David Bordelon 2009