Lesson Plans

Course Links

Lesson Plans

Course

Documents Links

Secondary Sources

Quick Links

Library

Links

Citing

Sources

Ragged

Dick; or Street Life in New York with Boot Blacks

Horatio Alger, Jr.

1867 (Serialization in The Student and Schoolmate),

1868 (Book)

Click here for links to online texts of the novel.

Interested in seeing how Richard turns out? Read the next novel in the series: Fame and Fortune.

Terms | Life | Class

Discussion | Group

Questions | Links | Pictures

http://www.etsu.edu/cas/history/resources/Private/Faculty/Fac_From1877ChapterDoc/

ChapterImages/Ch18HoratioAlgerJr.jpg

Terms to Know

Note Card Terms: class, religion,

self-made man, clothes, capitalism, con-men, Dick

Five Points: This was a particularly rough and poverty area of Manhattan, known as a breeding place for crime and social ills. The subtext here is that you cannot be "respectable" and life in Five Points. See page 133 in Ragged Dick (around #27) and page 134 for a map of the area.

Realism: In addition to the definition from the lesson plan on "Life in the Iron Mills," consider also that realism extends to they way characters speak -- in this case their use of dialect.

A broader consideration is the connection between the vogue of travel literature (non-fiction writing about far and not-so-far away exotic lands -- and Manhattan was [still is?] exotic to most Americans) and the place name details in the novel.

Self-Made Man: The belief that people themselves determine their own course of life. A strong belief in the power of individual.

This is one of the most tightly held myths in America, and explains why while the rest of the industrial world embraces a social contract that ensures basic standards for all, we ebb and flow, embracing the idea of a social safety net when times are hard, then rejecting it as times improve. It also explains our belief that just one tough hombre -- Marshall Dillion (60s); Rambo (70s); the guy in the Die Hard series (80s); the guy in the Matrix (90s); and Jack Bauer (00s) -- is all it takes to fix up the world. We just need to let him take the gloves off.

The Life

Here and for most of the remaining readings, I'll

refer you to the introductions in the textbook which are required

reading. For this text, the introduction is found in the preface.

For an overview of the times, see below

Overview: Ragged Dick; or, Street Life in New York with the Boot-Blacks . Literature and Its Times: Profiles of 300 Notable Literary Works and the Historical Events that Influenced Them . Joyce Moss and George Wilson. Vol. 2: Civil Wars to Frontier Societies (1800-1880s) . Detroit: Gale, 1997. From Literature Resource Center.

The Times

How prevalent was the idea of the self-made man as expressed in this

novel? Well . . . follow this link

to a 1881 American self-help book that sounds eerily like Mr.

Whitney in Ragged Dick.

For an idea of the social norms of the period, consider the following from William White's autobiography. White grew up a member of the "ruling class" (his words) in small town Kansas circa 1870s.

|

“But always I had an eye on the main chance. For I

was born with an acquisitive sense. My little bank on the clock shelf

at home was always well filled. For I was always looking for a chance

to run errands for someone with a dime. I remember vividly my father

coming up behind me one summer day on Main Street and whacking me with

his cane across my upturned bottom, to the astonishment of a stranger

before whom I was kneeling, shining his shoes: |

White, William Allen. The Autobiography of William Allen White. New York: MacMillan Company, 1946. Print.

In a similar vein, consider Henry Canby's reflections on class in Wilimington, Delaware, circa 1890:

|

"Our society in the town was thus a class society. There were the Negroes, and the working people, and the 'plain people,' and Us" (Canby 17). "The difference between them and Us was a subtle one of manners and tradition, chiefly tradition, for our manners were not always good. You lived according to a tradition of customs most conscious when breached; or you lived unconscious of a family past. You lived in two dimensions, the present and your breeding, or you lived in one dimension of current opinion" (Canby 20). There was a "felt distinction [. . . separating] the families I write about, more important than money or descent, -- their substitute for culture" (Canby 21). |

Canby, Henry Seidel. The Age of Confidence: Life in the Nineties. New York: Farrar & Rinehart, 1934.

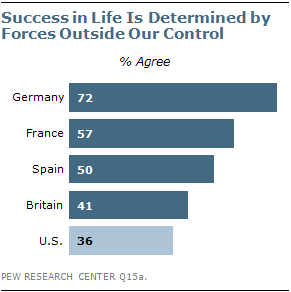

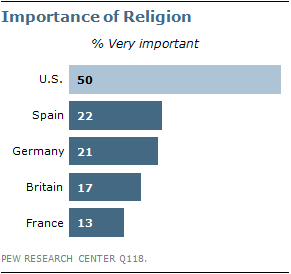

How do American feel now about the American Dream? Consider the results of a 2011 Pew survey of American values (the religion is thrown in for fun). |

|

When the Alger myth meets reality, the myth wins. But sometimes reality prevails.

On the power of myth and the American Dream.| “In The Black Swan, Taleb introduced the notion of a narrative fallacy to describe how flawed stories of the past shape our views of the world and our expectations for the future. Narrative fallacies arise inevitably from our continuous attempt to make sense of the world. The explanatory stories that people find compelling are simple; are concrete rather than abstract; assign a larger role to talent, stupidity, and intentions than to luck; and focus on a few striking events that happened rather than on the countless events that failed to happen. Any recent salient event is a candidate to become the kernel of a causal narrative. Taleb suggests that we humans constantly fool ourselves by constructing flimsy accounts of the past and believing they are true” (Kahneman) |

|

“Stories of how businesses rise and fall strike a chord with readers by offering what the human mind needs: a simple message of triumph and failure that identifies clear causes and ignores the determinative power of luck and the inevitability of regression. These stories induce and maintain an illusion of understanding, imparting lessons of little enduring value to readers who are all too eager to believe them.” (Kahneman) |

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking Fast and Slow.

And below, the power of myth in a comic form -- and how "we humans constantly fool ourselves" -- and let ourselves be fooled. . . .

And consider a different view from Twain "The Story of the Good Little Boy Who Did Not Prosper" and "The Story of the Bad Little Boy."

- Why a bootblack? Consider the connotations of this kind of work and the reality of 19th century urban environments.

- Let's trace out Dick's character: what adjectives would you use to describe him -- and where do you find support for that in the novel?

- Why list so many of Dick's faults right away (in chapter 1 pg. 5-6)

- What is Fosdick's role in the story? Consider, especially, his class.

- What role does chance play in the novel?

- page 66 has a great line ""It' s fashionable for young gentlemen to have private tootors to introduct 'em into the flower-beds of literatoor and science, and why shouldn't I foller the fashion? You shall be my perfessor; only you must promise not to be very hard if my writin' looks like a rail-fence on a bender." (66) What does this reveal?

- How does this read like a children's book? How does it seem like a "regular" novel?

- Just as in "Life," we have dialect. In that story, the dialect was used to _____. What's the purpose of the dialogue in this story?

- Imagine a conversation between Rebecca Harding Davis and Alger: how probable would she find Alger's story? What would you use to base your arguments?

- Why such an emphasis on "respectability" -- how does this figure into tensions in social class? And how does it mesh with the waves of immigrants coming to America? For instance, how are the Irish portrayed in the novel?

- Given the definition of literary realism, does this story make the cut? Why or why not?

- What does "respectability" entail, according to this text? Why would people want to achieve it? Why wouldn't some want to achieve it?

- What does "respectable" entail? Why does Dick want it so bad? Has "respectability" changed since the 1860s?

- How much of Dick's achievement are tied to luck? How much to his ability? Examples of each.

- In his book titled Great Fortunes and How

They are Made; or the Struggles and Triumphs of Self Made Men

(1872), James D. Macabe argues that

The chief glory of America is, that it is the country in which genius and industry find their speediest and surest reward. Fame and fortune are here open to all who are willing to work for them. Neither class distinctions nor social prejudices, neither differences of birth, religion, nor ideas, can prevent the man of true merit from winning the just reward of his labors in this favored land. We are emphatically a nation of self-made men. and it is to the labors of this worthy class that our marvelous national prosperity is due (5).

Does Ragged, written about five years earlier, reflect much the same ideas?

- Does Alger suggesting just ability is sufficient?

- Would this story work if it was set in the country? Why or why not?

- On page ix two critics note the connections between Alger's stories and American ideals. Is this still true? Do people still really believe this?

- Given this story, define the "Alger myth." How can such a myth empower a culture? How can it weaken a culture?

- Alger writes that he hopes his book "may also have the effect of enlisting the sympathies of his readers in behalf of the unfortunate children whose life is described, and of leading them to co-operate" with charitable organizations (1). Two questions: 1) does the novel succeed in this endeavor? 2) Doesn't this contradict the idea of the self-made man?

- Would this story work if it was set in the country? Why or why not?

- Why use humor in this story?

- Why so many scams/con men? Why include this in a story about a shoeshine boy who makes good? 11, 21, 24, 30, 44.

- On page 17, after dressing in Frank's suit, "I wonder if I aint dreaming" "I'm afraid I'm dreamin', and shall wake up in a barrel, as I did night afore last" (17). Given that dreams part of the unconscious, why bring them up here?

- Dick's love of violent melodrama (page 22). Why doesn't he go there anymore?

- What does this exchange b/t Frank and Dick show about the idea of the self-made man? page 26: "I really wish I could get somethin' else to do," said Dick, soberly. "I'd like to be a office boy, and learn business, and grow up 'spectable." "Why don't you try, and see if you can't get a place, Dick?" "Who'd take Ragged Dick?" "But you ain't ragged now, Dick." "No," said Dick; "I look a little better than I did in my Washington coat and Louis Napoleon pants. But if I got in a office, they wouldn't give me more'n three dollars a week, and I couldn't live 'spectable on that." "No, I suppose not," said Frank, thoughtfully. "But you would get more at the end of the first year." "Yes," said Dick; "but by that time I'd be nothin' but skin and bones."

- Page 28: what does this show is needed "I needn't have been Ragged Dick so long if I hadn't spent my money in goin' to the theatre, and treatin' boys to oyster-stews, and bettin' money on cards, and such like."

- PAGE 37: why include the "glass puddin'" glass put in bit?

- page 42 and page 43: why include this info about central park and the stores on Madison?

- PAGE 45 -- why is dick "contemptuous" of the country kid who gets fleeced?

- Why include this scene -- 51 concerning Dick's going to a more upright establishment and then deciding to get a room

- page 54 -- psychology: why isn't Micky Maguire glad that Richard is moving up in the world?

- page 62 -- Dick had good pluck -- what does that mean? OED it. And what about "mean" adj 1 on 63

- dialect: note that Fosdick speaks clearly

- What role does religion play in becoming respectable? See 69. But see also 63-64

- Why include note about Travis going to San Francisco ? 100

- How does capitalism figure into reform? cf. 101

Day 1

Remember to use quotes from the story to support your answers to these questions

- How do clothes symbolize Dick's position in society? Trace this throughout the story.

- What role does education play in the story?

- In his book titled Great Fortunes and How

They are Made; or the Struggles and Triumphs of Self Made Men

(1872), James D. Macabe argues that

The chief glory of America is, that it is the country in which genius and industry find their speediest and surest reward. Fame and fortune are here open to all who are willing to work for them. Neither class distinctions nor social prejudices, neither differences of birth, religion, nor ideas, can prevent the man of true merit from winning the just reward of his labors in this favored land. We are emphatically a nation of self-made men. and it is to the labors of this worthy class that our marvelous national prosperity is due (5).

Does Ragged, written about five years earlier, reflect much the same ideas? What would Davis – or Hugh Wolfe for that matter – say about this? And speaking of “Life in the Iron Mills,” which of these two stories is more mythic and which is more true to life: Ragged or “Life”?

- Given the definition of literary realism (again, as apart from realistic fiction in general), does this story make the cut? Why or why not?

- Why such an emphasis on "respectability" -- how does this figure into tensions in social class? And how does it mesh with the waves of immigrants coming to America ? For instance, how are the Irish portrayed in the novel?

- Why do some (Mickey Maguire comes to mind) seem to disdain respectability?

Day 2

- How much of Dick's achievement are tied to luck? How much to his ability? Examples of each. On page ix two critics note the connections between Alger's stories and American ideals. Is this still true? Do people still really believe this?

- Given this story, define the "Alger myth." How can such a myth empower a culture? How can it weaken a culture?

- How does Andrew Carnegie's view of America, as expressed in his essay "Wealth," compare with Alger's view, as expressed in Ragged? Try to connect specific wording from each.

- Alger writes that he hopes his book "may also have the effect of enlisting the sympathies of his readers in behalf of the unfortunate children whose life is described, and of leading them to co-operate" with charitable organizations (1). Two questions: 1) does the novel succeed in this endeavor? 2) Doesn't this contradict the idea of the self-made man?

- While ostensibly a poor boot-black, Dick exerts considerable influence on others -- getting people arrested, helping people recover from scams, saving lives. Since this is presented as realistic fiction (see author's preface), does this make the novel less realistic?

Radio

essay on con men in America

On the Media, March 6, 2009: "The Confidence

Man"

© David Bordelon 2009