Course Links

Lesson Plans

Course Documents

Links

Secondary Sources

Quick Links

Library Links

Citing Sources

|

Terms | Life | Times | Class Discussion | Group Questions | Links | Pictures | Quotes from Critics

![]()

anaphora A rhetorical figure of repetition in which the same word or phrase is repeated in (and usually at the beginning of) successive lines, clauses, or sentences. Found very often in both verse and prose, it was a device favoured by Dickens and used frequently in the free verse of Walt Whitman . These lines by Emily Dickinson illustrate the device:

Mine--by the Right of the White Election!

Mine--by the Royal Seal!

Mine--by the Sign in the Scarlet prison

Bars--cannot conceal!

Adjective : anaphoral or anaphoric . See also epistrophe .

"anaphora." The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Ed. Chris Baldick. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Web. 21 January 2010.

Lyric: Short, personal poems which present a unified examination of a particular topic.

Epic: Long poems, which tell a grand story -- i.e. the founding of a nation ( The Aeneid ) or the warrior's return home ( The Odyssey ) -- by following the career of heroes (or a single hero). Usually impersonal, with an elevated diction and episodic in nature.

Eros: Freudian term (from the Greek) suggesting the psychological and social aspects of conjugal love.Thanatos: Freudian term (from the Greek) suggesting the psychological ramifications of death (which, oddly enough for Freud, may include sexuality).

Abolitionism: The movement to repeal slavery in the U.S. (i.e. to "abolish" slavery).

Fugitive Slave Act: Part of the Compromise of 1850, this federal law made it a crime to assist a runaway slave. This transformed those Northerners who helped run the Underground Railroad into criminals. Both Thoreau and Emerson -- who were abolitionists -- felt that both the Missouri Compromise and the Fugitive Slave law were immoral and wrote against it.

aria Air. From the time of A. Scarlatti in the 18th cent. onwards this has had the definite implication of a more or less lengthy and well-developed solo vocal piece in ABA form normally called a da capo aria. The singer was expected to add ornaments in ...

aria A self-contained song for solo voice, often forming part of an opera or other large work. 1. Origins and meanings The closed, self-contained song is universal and immemorial, but it did not become associated with the word 'aria' until the 16th ...

![]()

Life

Whitman and T. met in 1856 or so. T. wrote to a friend "Whitman . . .

is apparently the greatest democrat the world has seen" (qtd. in

Harding 374).

In another letter about Whitman, T. wrote "I have just read his 2 nd edition (which he gave me) and it has done me more good than any reading for a long time [. . . .] As for its sensuality, --&it may turn out to be less sensual than it appeared -- I do not so much wish that those parts were not written, as that men & women were so pure that they could read them without harm, that is, without understanding them[ . . . .] On the whole it sounds to me very brave & American after whatever deductions. I do not believe that all the sermons so called tha thave been preached in this land put together are equal to it for preaching--" (qtd. in Harding 375)

"He freely admitted that he could never have written his poems if he had not first "come to himself," and that Emerson helped him to "find himself." I asked if he thought he would have come to himself without that help. He said, "Yes, but it would have taken longer." And he used this characteristic expression: "I was simmering, simmering, simmering; Emerson brought me to a boil."" (The Atlantic Monthly February 1902 Reminiscences of Walt Whitman by John Townsend Trowbridge)

Whitman represents the ecstatic, prophetic voice in American poetry. Thoreau writes a form of a jeremiad in Walden. He tries to scare us into reform by showing what we’re doing wrong. Whitman points out what we’re doing wrong, but focuses more on making what he thinks is right appealing.

James Miller argues in Leaves of Grass: America’s Lyric-Epic of Self and Democracy that the Song of Myself forms a spiritual narrative, and thus shows a movement from the opening to the closing (45). Is this true?

From Backward Glance O’er Well Traveled Roads

believes in a transendental view of the Nature, but admits its irrationality "While I can not understand it or argue it out, I fully believe in a clue and purpose in Nature, entire and several; and that invisible spiritual results, just as real and definite as the visible, eventuate all concrete life and all materialsm, through Time. (670).

Excerpts from his notebooks:

1853-54 notebook

"Bring in whole races, or castes, or generations, to express themselves-- personify the general objects of the creative and give them voice--every thing on the most august scale--a leaf of grass, with

its equal voice.-- [112] --voice of the generations of slaves--of those who have suffered-- voices of Lovers--of Night--Day--Space--the stars--the countless ages of the Past--the countless ages of the future-- " (qtd. in Miller 111-12)

""A poem in which all things and qualities and processes express themselves--the nebula--the fixed stars--the earth--the grass, water, vegetable, sauroid, and all processes--man--animals.'" (qtd. in Miller 113)

Rules for Composition

A

perfectly transparent plate-glassy style, artless, with no ornaments,

or attempts at ornaments, for their own sake-- ^ they only coming in

where ^ answering ^ looking well when like the beauties of the person

or character, by nature and intuition, ^ and never lugged ^ in in ^ in

by the colla[r] to show off . . .

Take no illustrations whatever

from the ancients or classics, nor from the mythology nor Egypt,

Greece, or Rome--nor from the royal and aristocratic institutions and

forms of Europe.--Make no mention or allusion to them whatever, except

as they relate to the New, present things--to our country--to American

character or interests.--. . .

Too much attempt at ornament is the blur upon nearly all literary styles.

Clearness, simplicity, no twistified or foggy sentences, at all--the most translucid clearness without variation.--

Common idioms and phrases--Yankeeisms and vulgarisms-- cant expressions, when very pat only.--

(Miller 124)

"Avoid all the "intellectual subtleties,'' and "withering doubts'' and "blasted hopes'' and "unrequited loves,'' and "ennui,'' and "wretchedness'' and the whole of the lurid and artistical and melodramatic effects.--Preserve perfect calmness and sanity" (qtd. in Miller 124) circa 1856

THE

ERRAND-BEARERS.; I6TH 6TH MONTH, YEARS 84 OF THE STATES. Over sea,

hither from Niphon, Courteous, the Princes of Asia, swart-cheek'd

princes,

New York Times (1857-1922). Jun 27, 1860. p. 2 (1 page)

Whitman in the Times -- only five years after the first Leaves of Grass.

Whitman Civil War Notebooks -- with commentary.

![]()

More biography: several years ago PBS sponsored a series of hour long television programs on American poets, including Walt Whitman. It's an excellent introduction to Whitman's life, the time he lived in, and his work.

The video is available at this link . Scroll down towards the bottom of the page to access it.

Use the following as a username and password

Username: occ.chat@yahoo.com

Password: poetry

The Walt Whitman Archive is, quite simply, the best page on any American writer. Scholarly yet accessible, it contains the kind of information that scholars would have to travel for months and do years of research to obtain. And it's all there for you with the click of a mouse. This is the real potential of the web.

A fine (and short) introduction to the first edition of Leaves of Grass (the edition we're reading) is found in Robert Hass's essay. But he didn't stop there. Take a listen to this interview from Fresh Air.

The Leaves of Grass Lexicon is a fine guide to contextual meanings of specfic words in the poem, particularly words which may be a bit obtuse for modern readers.

![]()

Times

Whitman is very much a creature of his times: he makes this explicit in a line from a late essay:

"No great poem or other literary or artistic work of any scope, old or new, can be essentially consider'd without weighing first the age, politics (or want of politics) and aim, visible forms, unseen soul, and current times, out of the midst of which it rises and is formulated" ("An Old Man's Rejoinder" 1249)

Whitman, Walt. "A Memorandum at a Venture." Complete Poetry and Collected Prose . Library of America, 1982: 1030-1036.

on the repression of sex in culture "non-scientific, non-aesthetic and eminently non-religious condition" (Whitman 1031)

"the sexual passion in itself, while normal and unperverted, is

inherently legitimate, creditable, not necessarily an improper theme

for poet . . ." (Whitman 1032)

"No, it is not the picture or nude statue or text, with clear aim, that

is indecent; it is the beholder's own thought, inference, distorted

construction" (Whitman 1036)

Haswell, Chas H. Reminiscences of an Octogenarian of the City of New York (1816-1860) . New York: Harper & Brothers, 1897.

Bowery Boys

"The Bowery, at this period, had become perhaps the most interesting street in the city, and so it remains, though with characteristics much altered from those of 1840. That date is about the mid-period of its peculiar notoriety as a native product, before the vast incursion of foreigners had given it its present cosmopolitan distinction. The "Bowery boy" (or b'hoy) and "Bowery gal" were at the height of their development as represented on the theatrical stage, with not overmuch exaggeration, by Chanfrau in the well remembered types of Mose, Sikesy, and Lize. The "bowery boy" flourished in his own proper time, and departed, never to return. He was the outcome of conditions that will not exist again, being primarily a product of the volunteer fire department system, and appearing in an age when the comparative smallness of the city allowed marked social peculiarities to become prominent, which would be lost amid the mass of people and the whirl of things in which all forms of singularity now appear and pass, with but a moment's notice and comment. "Bowery boys" were not wholly admirable beings, but they had some qualities that were admirable, and were much to be preferred to an later varieties of the genus ""rough." In their combats they were content with nature's weapons, avoiding murderous implements; they were mostly men of regular occupations and industry, the Boweryism being only their form of amusement in leisure hours; they were comparatively sober, and cultivated certain trait os manliness, especially a respect for women, which was traditional with them; and they were intensely American." this around 1840.

![]()

The New World .

November 1842 "First American Edition" American Notes for General

Circulation by Charles Dickens. Extra Series. Published complete. Vol.

II numbers 8,9. 12 1/2 cents

On last page, an advertisement:

Friends of Temperance, Ahoy!

Franklin Evans,

or

The Inebriate.

A Tale of the times -- By a popular American Author.

The novel, which is dedicated to the Temperance Societies and the friends of the Temperance Cause throughout the United States, will create a sensation, both for the ability with which it is written, as well as the interest of the subject, and will be universally read and admired. It was written expressly for the New World, by one of the best Novelists in this country, with a view to aid the great work of Reform, and rescue Young Men from the demon of Intemperance. The incidents of the plot are wrought out with great effect, and the excellence of its moral, and the beneficial influence it will have, should interest the friends of the Temperance Reformation in giving this Tale the widest possible circulation.

Terms: It will be issued as an Extra New World (octavo) on Wednesday, Nov. 22 at 12 1/2 cents single; ten copies for $1, or $2 per hundred. J. Winchester, 30 Ann Street, N. Y.

For more detail on his times, see Overview: Leaves of Grass. Literature and Its Times: Profiles of 300 Notable Literary Works and the Historical Events that Influenced Them. Joyce Moss and George Wilson. Vol. 2: Civil Wars to Frontier Societies (1800-1880s) . Detroit: Gale, 1997. From Literature Resource Center .

![]()

The Competition

Lydia Huntley Sigourney |

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow A Psalm of Life What the Heart of the Young Man Said to the Psalmist TELL me not, in mournful numbers, Life is real ! Life is earnest! Not enjoyment, and not sorrow, Art is long, and Time is fleeting, In the world's broad field of battle, Trust no Future, howe'er pleasant ! Lives of great men all remind us Footprints, that perhaps another, Let us, then, be up and doing, |

![]()

Questions to mull over as you interpret the Work

Power point on WhitmanEmerson from "The Poet" -- "bare lists of words are found suggestive to an imaginative and excited mind"

How is this quote connected to the poem?- Lines 1-29, what word is used the most?

- How is the poem a lyric?

- How is the poem an epic?

- How is the poem a mystic/visionary?

- Why the catalog?

- Why "Song"? Why not "Poem"?

- Why "celebrate"? Why not, for example, "praise"?

- Why a "yawp" (1321)

- How did the Puritan's feel about the body? How did Thoreau feel about the body? How does Whitman feel about the body?

- Which does the speaker value more: the spirit or the body?

- How does he bring everyone into his vision of an American?

- How does he address America's progress?

- Whitman and Thoreau met in 1856 or so. T. wrote to a friend "Whitman . . . is apparently the greatest democrat the world has seen" (qtd. in Harding 374). While Thoreau's comment may be a bit tongue in cheek, how does the poem show his love of democracy?

- Why "Leaves" of grass -- not blades?

- Why grass? Why not a rose? Or Laurel (and why did I bring up laurel? What's the connection between laurel and poetry?)

- "Divine am I inside and out, and I make holy whatever I touch or am touched from" 526 "The scent of these arm-pits is aroma finer than prayer" 527 What does he combine here?

- explain the progression of titles

- 1855 -- untitled

- 1856 -- Poem of Walt Whitman, an American

- 1860 -- Walt Whitman

- 1881 -- Song of Myself

- What's the difference/shifts b/t them?

![]()

Whitman Group Questions #1

Need quotes and line/page numbers for each answer.

- Whitman famously wrote "I was simmering, simmering, simmering: Emerson brought me to a boil." Emerson himself, after reading the first edition of Leaves of Grass , "I find it the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed" (637 Norton Critical). So, Mr. Transcendentalism feels this is the best of America -- why? What would Emerson (and, as noted in class, Thoreau), find congenial in Leaves of Grass ? (________ is another connection between transcendentalism and Whitman.)

- As you might have noticed, while Whitman celebrates life, he often includes stark images of death. Why? What does death signify for Whitman? (For Whitman, death is __________. )

- What is it with Whitman and "the merge"? Why does he celebrate it? (For Whitman, sex is __________.)

- Okay, how can a poem that starts off with "I celebrate myself" really be about the power of democracy? (consider this as For Whitman, democracy is _________.)

- When first (and second, and third) confronted with this work, a common reaction is "Huh? This is just a bunch of random thoughts." Is this true? Argue that ________ is one unifying feature of "Song of Myself."

Whitman Group Questions #2

Need quotes and line/page numbers for each answer.

- Writing about Whitman, the modern poet Randall Jarrell noted "If some day a tourist notices, among the ruins of New York City, a copy of Leaves of Grass, and stops and picks it up and reads some lines in it, she will be able to say to herself: 'How very American! If he and his country had not existed, it would have been impossible to imagine them’" (133). How is this true?

- While eventually titled "Song of Myself," this work had no title when it first appeared. Why? What does the lack of a title convey?

- Explain the connection between these two lines/ides

Emerson from "Self-Reliance:" "A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds" (1164)

Whitman:

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then . . . . I contradict myself;

I am large . . . . I contain multitudes.Do they reveal any intrinsic quality of Transcendentalism?

![]()

|

|

|

This is a letter from Emerson to Whitman welcoming the presence of a new poet. (Click to enlarge)

(From http://memory.loc.gov.mss.mcc.012.0001.jpg)

|

First publication of what became "Out of the Cradle," The Saturday Evening Press, 24 Dec. 1859 Unsigned review of above poem by . . . Walt Whitman "All About a Mocking-Bird." New-York Saturday Press. 7 Jan. 1860: 3.

|

|

Autograph page from a late edition of leaves of grass |

Whitmanesque poem from a weekly newspaper (Click to enlarge) |

Images from the Present

|

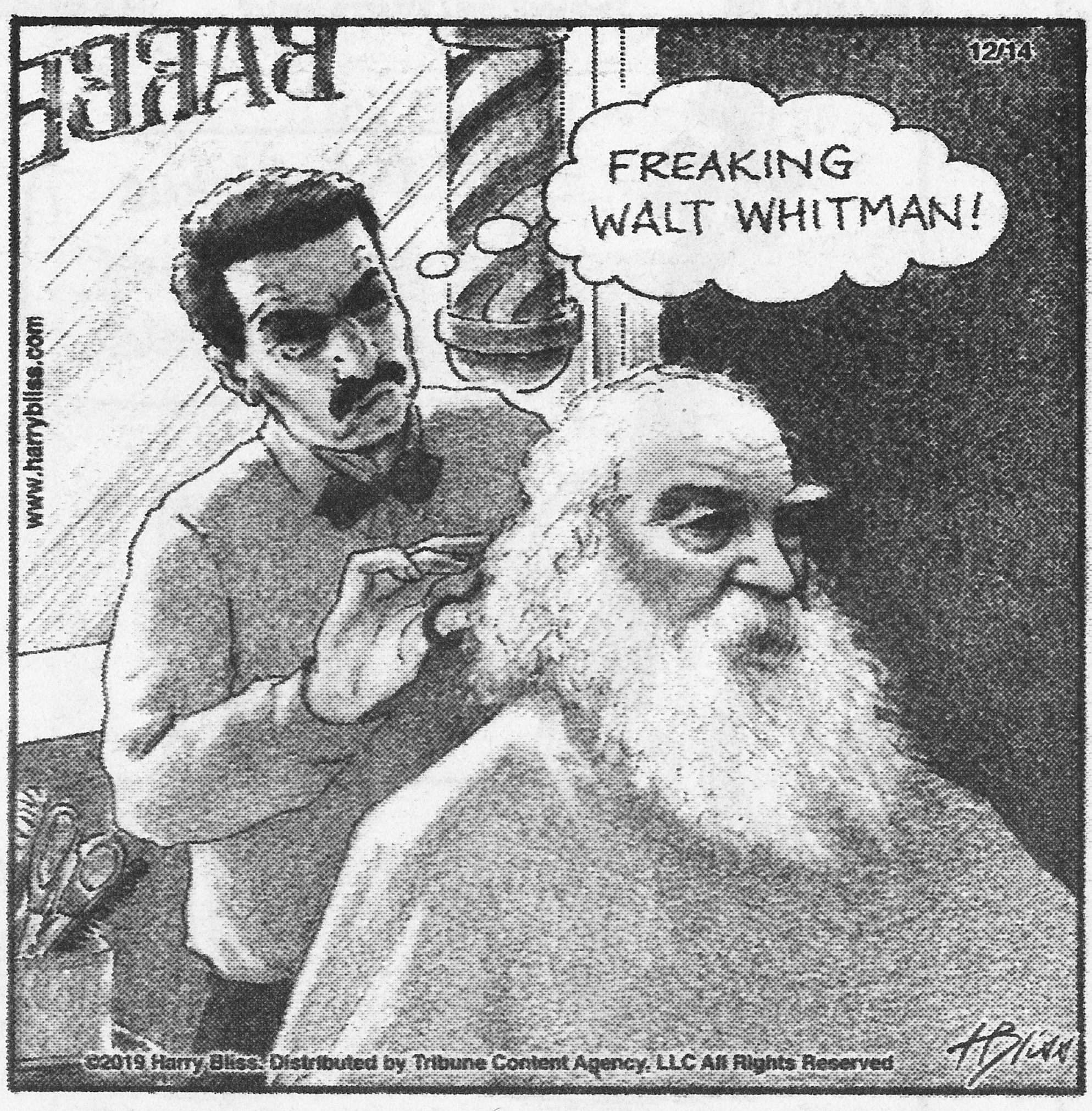

Bliss, Harry. Funny Times, Nov. 2020, pp. 12.

![]()

Library of Congress Whitman Homepage

Facsimile Autobiography (written in Whitman's own hand)

![]()

These essays (all from the New York Times) may assist in your understanding of Whitman

- Whitman's Multitudes, For Better And Worse

Michael Frank. New York Times (Late Edition (East Coast)). New York, N.Y.: Nov 18, 2005. p. E.2:33 - 'Leaves of Grass' at 150: As Exuberant and Encompassing as Ever; [Editorial]

Verlyn Klinkenborg. New York Times (Late Edition (East Coast)). New York, N.Y.: Jul 3, 2005. p. WK - Whitman's Song of Myself: The Poet as Self-Promoter

CHARLES McGRATH. New York Times (Late Edition (East Coast)). New York, N.Y.: May 22, 2005. p. 14LI.4 - Two New Old Books That Show Walt Whitman’s Different Selves. By Ted Genoways. August 30, 2017

Reynolds, David. Walt Whitman's America .

Whitman's father "exposed his family to the most radical thought of the day by subscribing to the Free Enquirer , edited by the militant reformers Robert Dale Owen and Fanny Wright. These and other labor radicals of the decade ushered in a rhetoric class conflict, defending 'productive,' virtuous workers against the 'idle' rich and calling for laws to aid the poor.

Both emotionally and intellectually, then, the impressionable Walt was immersed in the political ambience of class awareness that would eventually make him responsive to working-class culture in all its manifestations" (Reyonlds 27)

"In Whitman's mind, Long Island meant nature, Manhattan commerce and culture, and Brooklyn a propitious cross of both"(Reynolds 32)

"One of his main metaphors for the poet would be that of the joiner: joiner of sections of the nation, of different nations and peoples, of the past and the future." (Reynolds 32)

"Some have argued that his indolent, loafing persona stood in direct opposition to an increasingly capitalistic American culture where manhood was equated with pragmatic activity. To say this, however, is to ignore the way in which his poetry reflected a whole class of antebellum Americans with whom he identified deeply: the class of so-called loafers. These were mainly young working-class mena dn women who had been impelled by hard times to reject normal capitalist pursuits and find other means of gratification and amusement" (Reynolds 64)

© 2009 David Bordelon