Course Links

Lesson Plans

Course Documents

Links

Secondary Sources

Quick Links

Library Links

Citing Sources

|

Terms | Life | Times | Class Discussion | Group Questions | Links | Pictures | Quotes from Critics

Image from http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bf/Irving-Washington-LOC.jpg/421px-Irving-Washington-LOC.jpg

![]()

Terms and People to Know

Irony: A subtly humorous perception of inconsistency, in which an apparently straightforward statement or event is undermined by its context so as to give it a very different significance. In various forms, irony appears in many kinds of literature, from the tragedy of Sophocles to the novels of Jane Austen and Henry James , but is especially important in satire , as in Voltaire and Swift. At its simplest, in verbal irony , it involves a discrepancy between what is said and what is really meant, as in its crude form, sarcasm; for the figures of speech exploiting this discrepancy, see antiphrasis, litotes, meiosis . The more sustained structural irony in literature involves the use of a naïve or deluded hero or unreliable narrator

, whose view of the world differs widely from the true circumstances

recognized by the author and readers; literary irony thus flatters its

readers' intelligence at the expense of a character (or fictional

narrator). A similar sense of detached superiority is achieved by dramatic irony ,

in which the audience knows more about a character's situation than the

character does, foreseeing an outcome contrary to the character's

expectations, and thus ascribing a sharply different sense to some of

the character's own statements; in tragedies, this is called tragic irony . The term cosmic irony

is sometimes used to denote a view of people as the dupes of a cruelly

mocking Fate, as in the novels of Thomas Hardy . A writer whose works

are characterized by an ironic tone may be called an ironist . For a fuller account, consult Claire Colebrook , Irony ( 2003 ).

"irony." The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Ed. Chris Baldick. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Web. 27 January 2010.

Satire:

A mode of writing that exposes the failings of individuals,

institutions, or societies to ridicule and scorn. Satire is often an

incidental element in literary works that may not be wholly satirical,

especially in comedy

. Its tone may vary from tolerant amusement, as in the verse satires of

the Roman poet Horace , to bitter indignation, as in the verse of

Juvenal and the prose of Jonathan Swift (see juvenalian

). Various forms of literature may be satirical, from the plays of Ben

Jonson or of Molière and the poetry of Chaucer or Byron to the prose

writings of Rabelais and Voltaire . The models of Roman satire ,

especially the verse satires of Horace and Juvenal, inspired some

important imitations by Boileau , Pope , and Johnson in the greatest

period of satire -- the 17th and 18th centuries -- when writers could

appeal to a shared sense of normal conduct from which vice and folly

were seen to stray. In this classical tradition, an important form is

'formal' or 'direct' satire , in which the writer directly addresses

the reader (or recipient of a verse letter) with satiric comment. The

alternative form of 'indirect' satire usually found in plays and novels

allows us to draw our own conclusions from the actions of the

characters, as for example in the novels of Evelyn Waugh or Chinua

Achebe . See also lampoon . For a range of introductory accounts, consult Ruben Quintero (ed.), A Companion to Satire ( 2006 ).

"satire." The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Ed. Chris Baldick. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Web. 27 January 2010.

![]()

![]()

Short background essay on social aspects of "Rip Van Winkle"

This is one of those snarky little tales that, on the surface, appears to be just an amusing bit of Americana, but when examined more closely, reveals the power of metaphor, symbol, and how narrative can be used as satire.

"Henry B. Miller was in St. Louis when he participated in his first elections. The initial one, for city officers in the spring of 1838, was a memorable induction for the young man into the sport of American politics, even though 'it went off middling quiet, as far as regards fighting.' The second, in August of the same year for state and national positions, was a notable brawl which 'learnt me,' Miller wrote, 'that there was a many rowdies amongst the Whigs as amongst the Democrats.' Miller's first voting experiences included many common aspects of belligerent antebellum democracy and suggest how much intimidation, bruising, and violence the American system incorporated into its democratic virility.

In the 'middling quiet' city election, Miller recounted many 'amusing sights':

Each one exerting himself for his respect candidate, talking loud and fast . . . . raising the one above the superior class of mankind and sinking the other below the lowest of mankind to whom the Devil himself would be virtuous . . . . bringing forward the voters telling them who to vote for, and challenging the votes of everyone with who they have the faintest shadow of a chance; handing out tickets, crossing out names, with many arguments pro and con

(Grimestead America 181)

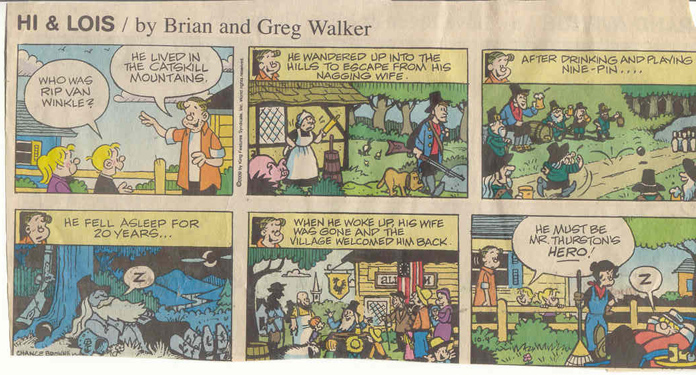

And "Rip" exerts a strong pull on our current mythos as well: consider the cartoon handed in by a student.

![]()

- Where does Rip escape to? How does this mark a difference with the Puritans?

- Why the old "found among the papers" bit? (cf. Hawthorne, Carlyle)

- Would readers take this "found" trope seriously?

- How is his wife characterized? 982 What about his treatment of other women?

- Does Rip seem like a typical colonialist? How?

- Why open with a reference to Nordic gods as opposed to Greek or Christian ones?

- Are we meant to agree or disagree with Rip’s worldview? How can you tell? Is it good to get drunk? Or to be idle?

- What does he like best to do? What’s his dog’s name?

- How has life changed in twenty years?

- Let’s look at two contrasting paragraphs: description of the tavern 983/988

- What is Irving saying about the American political situation?

- What about the economic?

- How can you read this story from a Freudian standpoint? (i.e. Id, Ego, Superego)

- What is this story, given the reference to Henry Hudson (the old men in the hills) and the twenty years sleep, and the difference between the story past and the story present, saying about history?

- Does Rip lack a work ethic? What does he seem to lack?

- Why was the old tree removed and a flagpole put in its place?

- What's the first question the men ask Rip when he returns from the village? How does it contrast with the earlier village?

![]()

- At least one critic takes a larger view of the purpose of the story, arguing for a more cultural reading:

Irving wishes in a gentle way to remind his readers that American "exceptionalism" should not be taken too far, and that, for all their innovativeness in the history of human societies, the Americans should not forget that they are human beings and therefore need a sense of the communal past, as have all societies heretofore. (Conlin)

Let's take Conlin at his measure: How could this story be read as a cautionary tale about American exceptionalism?

- Let's consider another critic's interpretation who looks at this story from an economic perspective:

The conflict between nature and the 'civilized' world of the marketplace is at the heart of Rip Van Winkle. And it is at the heart of 'Rip Van Winkle' because it was at the heart of the development of America in Irving 's time. (Ozersky)

Consider, as well, the following from Alexis de Tocqueville's 1835/40 Democracy in America

"I know of no country, indeed, where the love of money has taken a stronger hold on the affections of men and where a profounder contempt is expressed for the theory of the permanent equality of property." (Tocqueville 51)

How does this story show a conflict b/t nature and the civilized world of the marketplace?

- How does this compare and/or contrast with Franklin ?

- How does this compare and/or contrast with the Puritan writers

![]()

Hudson River School:

Designation applied to the earliest distinctively American landscape

specialists. Their work combined meticulous, factual description with

romantic feeling for the beauty, grandeur, and nobility of American

scenery. Active from the 1820s, nearly all were native-born, although

most studied and traveled in Europe. There they absorbed traditional

skills and theories, but their attention to American subjects gave

their work an indigenous flavor and helped to crystallize an optimistic

national consciousness. The style peaked from the 1840s through early

1860s. By about 1880 it had gone out of fashion. Although centered in

New York and bound by friendships, the Hudson River School painters

never formally organized. Originally a derogatory tag, the name came

later, when the style was seen as naive, finicky, and provincial. Usage

of the term has been inconsistent. Some observers have employed it to

embrace all realistic nineteenth-century landscapes, but art historians

today generally limit its applicability to a smaller group of painters

whose work most consistently exemplifies the School 's salient

characteristics. Thomas Cole 's landscapes proved pivotal to the birth of the School . Such earlier landscapists as Alvan Fisher and Thomas Doughty are variously considered precursors or early adherents. Core members of the School include Asher B. Durand , John Kensett , Worthington Whittredge , and Jasper Cropsey . Although some writers include them, Albert Bierstadt , Frederick Church , and Martin Johnson Heade ,

among other major landscapists, are often now seen as related figures

whose interests diverged from those of the central group. Typical

Hudson River School landscapes picture undefiled scenery of the

northeastern United States, chiefly New England and New York State. The

Hudson River Valley, including the Catskill Mountains, served as the

earliest and most frequent locus of activity. Views may be intimate or

sweeping, but vegetation, rocks, clouds, and other features are acutely

observed, often painted with tiny brushes for maximum detail. Light is

carefully rendered, but also controlled to contribute to harmonious or

even transcendental effects. Typically, the mood of the paintings is

pastoral and poetic, although some convey the awesome impassivity of

untouched nature. Painters and contemporary observers frequently read

patriotic meanings into the views, which were seen as evidence of the

young country's inherent greatness and possible superiority to the Old

World. Moreover, interpreting the landscapes as evidence of God's

handiwork, many also read moral and spiritual messages there. Hudson

River School painting paralleled contemporaneous literary responses to

landscape, as in James Fenimore Cooper's novels, the poetry of William

Cullen Bryant, and the philosophical ruminations of Ralph Waldo Emerson

and Henry David Thoreau. The period's responsiveness to nature

benefited from familiarity with English romantic art and literature, as

well as by an urbanizing population's nostalgia for the country.

"Hudson River School." The Oxford Dictionary of American Art and Artists. Ed. Ann Lee Morgan. Oxford University Press, 2007. Oxford Reference Online . Web. 27 January 2010.

![]()

Hudson River School of artists

![]()

"Irving wishes in a gentle way to remind his readers that American "exceptionalism" should not be taken too far, and that, for all their innovativeness in the history of human societies, the Americans should not forget that they are human beings and therefore need a sense of the communal past, as have all societies heretofore" (Conlin)

"Even America has its demigods and superhuman founders who dwell in the mountains as a kind of brooding presence overlooking the community for all time. Rip's America is not really distinct from other, more traditional societies. It too has its divine origins not subject to strictly scientific study." (Conlin)

"But a "general shout burst from the bystanders--|A tory! a tory! a spy! a refugee! hustle him! away with him!'" (36). Something like mob-rule has come to the village along with the new republicanism. Life is politicized, and no one can afford to be outside the mainstream." (Conlin)

"Catherine Zuckert argues that there is "a characteristically American motif" in the great works of American literature anchored in the principles of the Declaration of Independence and which points back to the State of Nature philosophy of Hobbes and Locke. According to Zuckert, the "naturalistic" school in American fiction led by Cooper, Hawthorne, and Melville, involves the return to the "state of nature" in order to find a basis for the critique of American life. Zuckert argues that these "withdrawals" constitute "investigations" into "the purported basis of the American political creed" with its "Lockean" or "social contract theory" roots (246)." (Conlin)

"Rip is a reminder that all communities, no matter how free and enlightened they become, need to be attentive to their past, and need, no matter what their prosperity and success, some sense of the mysterious and awe-inspiring. Rip's experience is akin to a Biblical Revelation, except that his encounter is with local gods. Rip's "polytheistic" experience suggests an association with the Greeks and their "political" gods of the polis. Rip's tale-telling serves a political function in that it tends to enchant the history of his community and to give it roots in a mythic past. Rip reminds his auditors that their community has a long and various history even behind the original Dutch settlers. " (conlin)

"Like the mythic 'noble savage' of Rousseau, or the heroes of westerns, Van Winkle is an Edenic figure, a man unfettered by society. That, above all else, is the source of his enduring appeal." (Ozersky)

"The conflict between nature and the "civilized" world of the marketplace is at the heart of Rip Van Winkle. And it is at the heart of "Rip Van Winkle" because it was at the heart of the development of America in Irving's time." (Ozersky)

"The coastal colonies, on the other hand, were deeply committed to commerce from their founding. This tension was to inform the entire early history of America. Jefferson's yeoman farmers and Hamilton's manufacturers, Democratic Republicans and Federalists, country and city. Everywhere market culture encountered subsistence culture, it derided it as lazy, backward, idle." (Ozersky) VERY TRUE – SEE FRANKLIN

"At any rate a primal, primeval myth has been postulated (by Joseph Campbell in his Hero with a Thousand Faces), and has been described--as a "separation from the world, a penetration to some source of power, and a life-enhancing return." (Young)

© 2009 David Bordelon