Course Links

Lesson Plans

Course Documents

Links

Secondary Sources

Quick Links

Library Links

Citing Sources

|

Terms | Life | Times | Class Discussion | Group Questions | Links | Pictures | Quotes from Critics

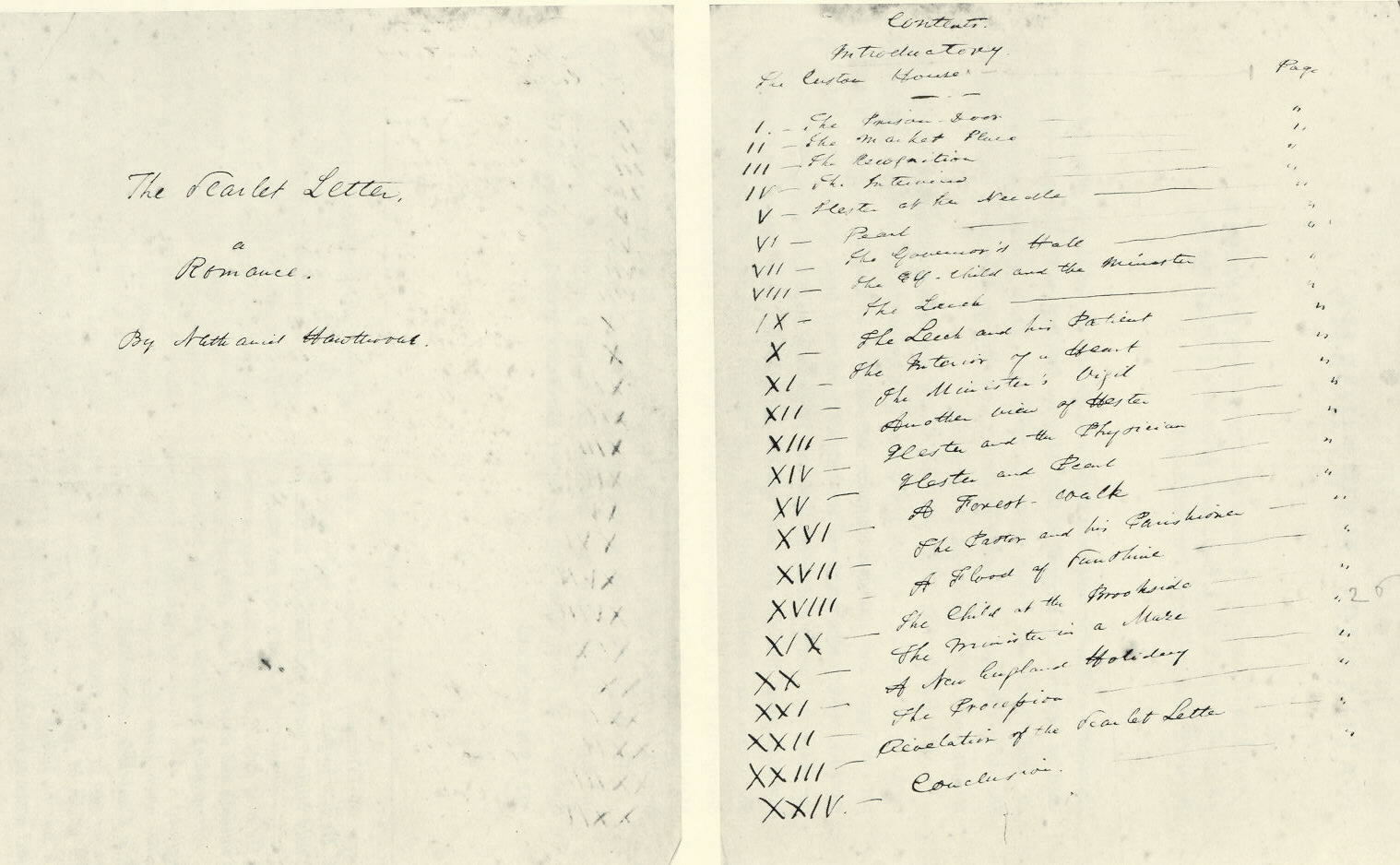

Image from http://www.hawthorneinsalem.org/images/image.php?name=MMD1853

Hawthorne in 1850, two months after Scarlet Letter was published.

![]()

Introduction

True confession time. When I first read this novel in high school, I

couldn't finish it.

The problem? Two-fold: number one, I was too young and ignorant

to appreciate it; number two, I couldn't get past the "Custom House"

section.

Flash forward to college. When I read the novel for an American Literature survey course, I thought it was the best novel ever written. The change? Two-fold: number one, I was older (though not necessarily less ignorant) and could better appreciate a story about love; number two, I rushed through the "Custom House" (though I lingered a bit in the attic when Hawthorne writes about finding the old manuscript) to get to the story itself.

Why am I telling you all this? Because I don't want you to get turned off to the novel by getting lost in the "Custom House" as I did. Thus, we'll be starting from Chapter 1 of the novel itself and getting back to the "Custom House" after reading the novel proper.

![]()

Terms and People to Know

Allegory:

a story that can be read on multiple levels -- a literal level (what is

happening in the story), and more broadly, as a symbolic representation

of another meaning (religious, political, cultural, ethical,

historical, etc.). Typically, allegories employ characters whose names

personify a type (Goodman, Evangelist, Christian, Faith), and place

them in similarly broad setting (the Forest, Vanity Fair, Slough of

Despond). Writers use allegories to invest a seemingly simple plot (man

who thinks he’s good goes to forest and returns not so good) with

richer meanings (note plural). Fables and parables are kinds of

allegories.

Cult of True Womanhood: This placed women on a pedestal -- and kept them in place -- through a culturally reinforced emphasis on piety, purity, and domesticity. See essay by Catherine Lavender, director of American Studies at CUNY Staten Island, for a brief but thorough explanation of this topic.

Modern version of a similar ideal? See the 2000 Southern Baptist Convention Confessional statement.

Faustian: Faust is a character in an old German folk tale, revived by artists throughout the ages. He's an alchemist -- an early scientist -- possessed with a desire to obtain all knowledge. He makes a deal with the devil: devil gets his soul, and Faust gets all knowledge. Hence the adjective: A "faustian" character is a person who strives after knowledge -- to his/her detriment.

Liminal:

A state of being on the edge or margins of society, applied

archaeologically in three interrelated ways. Physical liminality may be

seen in terms of a place or activity being detached from the centre of

things (e.g. a cemetery placed on the boundary of a territory) in a

'liminal zone'. Social liminality may be seen in terms of subcultures

who are distanced from those who see themselves as the mainstream (e.g.

peripatetic workers who join a community for while but then move on).

Cultural liminality refers to a stage in the progression through a

'rite of passage' such as birth, initiation, marriage, or death, which

often follows a tripartite structure involving separation, liminality,

and reincorporation.

"liminal" The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology. Timothy Darvill. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Web. 21 November 2009.

Romance: Hawthorne repeatedly stated that he was not writing realistic fiction (the then dominant mode of fiction with writers such as Charles Dickens); instead he wrote romances. He offered the following definition in his Preface to The House of the Seven Gables:

When a writer calls his work a Romance, it need hardly be observed that he wishes to claim a certain latitude, both as to its fashion and material, which he would not have felt himself entitled to assume had he professed to be writing a Novel. The latter form of composition is presumed to aim at a very minute fidelity, not merely to the possible, but to the probable and ordinary course of man’s experience. The former [ . . .] has fairly a right to present that truth under circumstances, to a great extent, of the writer’s own choosing or creation. If he think fit, also, he may so manage his atmospherical medium as to bring out or mellow the lights and deepen and enrich the shadows of the picture.

This expands the range of his fiction because it allows him to employ the supernatural into his fiction without readers rejecting it as "unrealistic."

Reform: Emerson in a 1840 letter to the English writer Thomas Carlyle: "We are all a little mad here with numberless projects of social reform. Not a reading man but has the draft of a new community in his pocket'" (qtd. in Nye Society 54).

Sensational Literature: Sensational fiction of the 1820--1870 period consisted largely of inexpensive, mass-produced pamphlet novels, many of them in yellow paper jackets embla-zoned with racy titles in lurid dark lettering and melodramatic lithographs that ranged from the titillating to the horrific. Designed as ephemeral entertainment for a mobile readership, this fiction was an important barometer of popular taste and a revelation of such issues as class relations, gender, ethnicity, and the contexts of major American literature. Read rest of essay

Reynolds, David. "Sensational Fiction." American History Through Literature

![]()

Life

See the textbook and read the essay on Hawthorne in the Dictionary of Literary Biography.

![]()

Times

Social/Cultural

What's this? A female heroine -- who committed adultery -- in the middle of the nineteenth-century ? Wasn't antebellum America the time when women were "Angels of the hearth" -- pious and always content with their lot?

Well . . . not exactly. The first American woman's rights convention was held in Seneca Falls, New York in 1848, just two years before the novel was published. At that convention, leaders such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott offered their "Declaration of Sentiments" which began "The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her" (91). While the prevailing ethos valued submission from women, it is obvious that some objected to the yoke.

Adultery? The trope of the paradoxically virtuous "fallen woman" regularly appeared in the fiction of the period, both English (cf. Nancy in Dickens's Oliver Twist [1838]) and in various essays, stories and novels in America. In both English and American culture, this idea of a woman retaining a kind of innocence (though she is inevitably punished for her "sins") in spite of being tainted by sexuality was connected to the reform movements so prevalent in the period.

Nineteenth-century was obsessed with the perfectibility of man. To that end, any number of reform movements, such as temperance, anti-slavery, anti-prostitution, feminism, periodically swept the land. In most cases, these movements agitated for change by trying to make the dominant, or hegemonic, culture more accepting of differences. How does this fit into the novel? Well, why did the Puritans come to America? Were they a kind of reform movement as well? A more germane questions is what does Hawthorne suggest about these movements?

Consider as well what these two excerpts reveal about the nineteenth century mindset

Upon returning from September 1850 Sunday morning service at Broadway Tabernacle, a New Yorker named William Hoffman, who was punctilious about his religious observances, had the "pleasure" to observe through a peephole in his room "the perfect female form of the two Miss Whitings, young girls or ladies about 17 & 19 years old . . . for about 20 minutes with every part of their bodies exposed." Without revealing any compunctions, he notes that he attended the Tabernacle again that evening (Saum 35).

Grayson, P. W. From Vice Unmasked, an Essay, Being a Consideration of the Influence of Law Upon the Moral Essence of Man. New York, 1830. Rpt. in Notions of the Americans 1820-1860. Ed. David Grimsted. New York: George Braziller, 1970. 45-60.

"Wherever we find evil, no matter how venerable it may seem from the sanctity of its origin, or reputable from the customary regards of men, we should not scruple, even for an instant, to tear off the disguises which conceal its enormity, and, exposing the viciousness of its essence, strike for its extinction!" (Grayson 46)

The Arts

One thing that may have lost some of its punch to our jaded

sensibilities (and due to Hawthorne's subdued tone) is the salacious

nature of the novel. This is after all a seduction story -- and a

minister is involved. While some contemporary readers may have

objected to the scandalous subject matter, Hawthorne was only

exploiting a well-established literary convention: the Reverend

Rake. The 1840s saw a rise in writings (both fiction and

non-fiction) dealing with ministers caught in comprising

positions. In an 1848 article in the Police Gazette, a writer warned

The reader now may see what some of these preachers are! Hypocrisy, cant, espionage, malice, lust, and all uncharitableness pour from their hearts as filth from a corrupted fountain, and while they raise their voices to rebuke the harmless derelictions of the common world, they stand chargeable with the most heinous crimes themselves and reeking with defilement to the very lips. (qtd. Reynolds 261)

Indeed, Hawthorne's own "The Minister's Black Veil" (1836) dealt with a minister who committed an unknown sin and wore a black veil to cover his face for the rest of his life. In other stories, such as "Young Goodman Brown," and "Ethan Brand," he probes the psyche of people tortured and eventually consumed by secrets.

Another trait of popular novels from the period was the likeable criminal, particularly when that criminal is an "outsider" trying to buck the tide of the mainstream culture.

More broadly, Hawthorne wrote during the heyday of the realistic novel -- English writers like Dickens who often wrote about orphans who start out poor but through their innate goodness (and because they were secretly part of wealthy families) become wealthy, were best sellers. Among American writers, the main realistic writer (and his main competitors, as his comment below demonstrates) were what we now call "Domestic Women's Fiction" -- works by Maria Susana Cummings The Lamplighter (1854) and Susan Warner's Wide Wide World (1850) often wrote about orphans who start out poor but through their innate goodness (and because they were secretly part of wealthy families) become wealthy (and yes, the repetition is intentional). Harriet Beecher Stowe's monumental Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852), like Jacob's Incidents , borrowed both from the traditions of Domestic Women's fiction and reform literature, and became the best selling novel written by an American in nineteenth century America . Hawthorne felt this competition keenly: he infamously wrote in an 1855 letter to his publisher William D. Ticknor that " America is now wholly given over to a damned mob of scribbling women, and I should have no chance of success while the public taste is occupied with their trash--and should be ashamed of myself if I did succeed. What is the mystery of these innumberable editions of The Lamplighter [by Maria Susanna Cummins], and other books neither better nor worse? Worse they could not be, and better they need not be, when they sell by the hundred thousand." This a cry from the heart both aesthetically (he genuinely found the books artistically flawed) and economically (if readers are spending money on these books, they're not spending money on his own).

Hawthorne touches on the differences between realism and romance in the "Custom House" chapter. By categorizing the novel a romance rather than a novel, Hawthorne turns it from a reportage of facts (a la' Dickens and his nemesis -- Cummings, Warner, et al.) to a text which can revel in ambiguity and the supernatural.

Science/Philosophy

The nineteenth-century is, of course, when the Industrial Revolution

kicked into high gear, and most Americans welcome new technologies with

open arms (some things never change, eh?). Associated with this

was a belief in the benefits of science and rationality (traces of the

Enlightenment?). Of course, the science during this period, with

its phrenology, magnetism, and mesmerism -- was often of a dubious

nature. And not everyone welcomed the rise of intellect with open

arms. For instance, some took a romantic stance towards science

-- i.e. nature good, science . . . if not bad, than not so

good. Additionally, the skeptical view required by science

often lead to questions about the piety of those who studied it.

And questions of piety in the predominately christian culture of

nineteenth-century America were not taken lightly.

![]()

NOTE: Questions are a bit ragged here.

Day one

- Opening setting sets theme: "sad-colored" -- not a color, just sad

- Narrative intrusion: How is the first paragraph different from second? Who's talking here? Narrator. Why would he feel that he has to come into a story. Contrast with Flaubert (and this in France ) who was tried for morality crimes for Madame Bovary (1856) which also dealt with an adulteress. What was the difference? Objectivity

- Utopian communities: what is going on here? How does he feel about these communities? How can you tell (prison/burial ground)

- We're staring at a prison door -- what does a reader wait for with a door? And who is going to come out of prison door? We haven't even met this person, yet how is the narrator getting us to think about him/her? How is he making us feel about the people who have condemned the prisoner? How can you tell? Sympathy for a criminal? Is this common in America ?

- Note the contrasting symbols -- how is the prison symbolized? "black flower" -- what's the contrast? "wild rose" -- what distinctions are made here? Black flower=civilization=control=bad wild rose=forest=freedom=good

- Why Anne Hutchinson? Why "sainted"

- Why a threshold? (the word occurs 12 times in the text) Liminal. What does this enable Hester to do? What's the contrast here? (Dimmesdale -- town/pastor/hegemony)

- Liminality (from the Latin

word limen, meaning "a threshold") is the quality of the second stage

of a ritual in the theories of Arnold van Gennep, Victor Turner, and

others. In these theories, a ritual, especially a rite of passage,

involves some change to the participants, especially their social

status.

- The liminal state is characterized by ambiguity, openness, and indeterminacy. One's sense of identity dissolves to some extent, bringing about disorientation. Liminality is a period of transition, during which your normal limits to thought, self-understanding, and behavior are relaxed, opening the way to something new.

- Why is Pearl a girl? How would the story be different if the child is a boy?

- Darkness and light: " like a black shadow emerging into sunshine, the grim and gristly presence of the town-beadle" (1380); " A blessing on the righteous colony of the Massachusetts , where iniquity is dragged out into the sunshine!" ( 1381); John Wilson -- "eldest clergyman of Boston" " There he stood, with a border of grizzled locks beneath his skull-cap, while his grey eyes, accustomed to the shaded light of his study, were winking, like those of Hester's infant, in the unadulterated sunshine" (1387), 1388

- What is around Hester's heard on 1381? What does this do? (see 1382 for more detail)

- Heart: "People say," said another, "that the Reverend Master Dimmesdale, her godly pastor, takes it very grievously to heart that such a scandal should have come upon his congregation." (1380); ""She will not speak!" murmured Mr. Dimmesdale, who, leaning over the balcony, with his hand upon his heart, had awaited the result of his appeal. He now drew back with a long respiration. "Wondrous strength arid generosity of a woman's heart! She will not speak!" (1389); "Chillingworth " "He bears no letter of infamy wrought into his garment, as thou dost, but I shall read it on his heart." (1393)

- What does Pearl want to say on 1389? "held up its little arms, with half pleased, half plaintative murmer"

- Who calls out from the crowd "Speak; and give your child a father!" (1389) Why?

- Why give Chillingworth a deformity? Why have him first clad "in a strange disarray of civilized and savage costume" (1384)

- Why have Chillingworth stay in prison? "He was lodged in the prison, not as suspected of any offence, but as the most convenient and suitable mode of disposing of him" (1390)

- Which work that we've read does this remind you of? "Thou and thine, Hester Prynne, belong to me. My home is where thou art and where he is. But betray me not!" (1393); "She was patient--a martyr, indeed but she forebore to pray for enemies, lest, in spite of her forgiving aspirations, the words of the blessing should stubbornly twist themselves into a curse." (1398)

- Which "nature" is the narrator referring to? 1406 "between the public on the one side, and a lonely woman, backed by the sympathies of nature, on the other" (1406)

- Why include note of luxury among the Puritan hierarchy? (1408, 1410)

- What does the letter teach? ""Nevertheless," said the mother, calmly, though growing more pale, "this badge hath taught me--it daily teaches me--it is teaching me at this moment--lessons whereof my child may be the wiser and better, albeit they can profit nothing to myself." (1411)

- What is Hester doing in her conversation with Dimm. On 1413? "I will not lose the child! Speak for me! Thou knowest--for thou hast sympathies which these men lack--thou knowest what is in my heart, and what are a mother's rights, and how much the stronger they are when that mother has but her child and the scarlet letter! Look thou to it! I will not lose the child! Look to it!" (1411)

- Who does Dimms. Remind you of on 1416-17: "a frequent practice, in order to keep the grossness of this earthly state from clogging and obscuring his spiritual lamp." What two ideals are symbolized when Dimm and Chill move in together? 1420 "Here the pale clergyman piled up his library, rich with parchment-bound folios of the Fathers, and the lore of Rabbis, and monkish erudition, of which the Protestant divines, even while they vilified and decried that class of writers, were yet constrained often to avail themselves. On the other side of the house, old Roger Chillingworth arranged his study and laboratory: not such as a modern man of science would reckon even tolerably complete, but provided with a distilling apparatus and the means of compounding drugs and chemicals, which the practised alchemist knew well how to turn to purpose."

Day Two: Revolution, The Woman question, Faustian and Science

- Why is Pearl a girl? How would the story be different if the child is a boy? Consider the following: "As the 1700s progressed, the view of children as innately sinful waned; by the beginning of the 1800s, the belief in children as sentient beings shaped by adults and society dominated" (Newton 21) .

- How do the readings on 1848 and on women's roles in 19th century America reflect upon the novel?

- Why does the meteor flash in the sky as Dimmsdale is on the scaffold? What connections to the dark/light symbolism do you see there? Connections to the themes of uncertainty/mystery/romance?

- What does Hester suggest needs to happen to sciety at the bottom of 1441?

- What's the connotation of "flicker" (1443)?

- Could this passage be a critique of Transcendentalism?

In such a case, it could only be the symptom of a highly disordered mental state, when a man, rendered morbidly self-contemplative by long, intense, and secret pain, had extended his egotism over the whole expanse of nature, until the firmament itself should appear no more than a fitting page for his soul's history and fate. (1436)

- Why does Pearl make a letter A upon her chest? Why is it green? Why eel-grass? (1448)

- What are some passages that connect the Faust myth to Chillingworth? Why bring this in? How is science viewed in this text?

Day Three: Forest, Scaffold, Custom House, General questions

- What distinction does Dimmsdale make with the following comment: " Of penance, I have had enough! Of penitence, there has been none!" 1455

- Connections to "Young Goodman Brown" 1422; 1455 Dimms. In despair "But now, it is all falsehood!--all emptiness!--all death!" (1455)

- Hester tells Dimmsdale: " "What we did had a consecration of its own." (1457). What is she referring to? How can this be consecrated? Has the letter done its office yet?

- Role reversal - Dimmsdale is feminized, Hester made masculine: Hester is stronger "strove in vain to do so" (1457); Earlier, the narrator notes that "Some attribute had departed from her, the permanence of which had been essential to keep her a woman." And see rest of quote (1440); Hester made more intelligent and wily ""Think for me, Hester! Thou art strong. Resolve for me!" ""Be thou strong for me!" answered he. "Advise me what to do." (1458); "Alone, Hester!" (1459) Why? Why make this difference?

- In "The Pastor and his Parishinor" Hester suggests that Dimms. Can get away from "his power and knowledge!" (1458). Who does the "his" refer to?

- "Leave this wreck and ruin here where it hath happened [. . . .] Begin all anew!" (1458); "Give up this name of Arthur Dimmesdale, and make thyself another" (1459) How is this an American ideal?

- Important quote -- on the letter itself -- connects it to the "untamed forest" 1459. how does it connect with the idea of "The scarlet letter had not done its office" . SECOND PART. Which "character" is bringing this all up?

- Very powerful word for a work based on Puritan: as the narrator discusses Dimmsdale's and Hester's plans to escape Boston , he writes: "Were such a man once more to fall" (1460) what falls are he talking about?

- How can readers (particularly 20 th century readers) see the forest where they decide to flee the sterile bonds of Puritanism: positive or negative? How does the narrator see the forest? When Dimms. Decides to leave, feels an "exhilarating effect--upon a prisoner just escaped from the dungeon of his own heart--of breathing the wild, free atmosphere of an unredeemed, unchristianised, lawless region" (1460); compare with the description of the forest: "Such was the sympathy of Nature--that wild, heathen Nature of the forest, never subjugated by human law, nor illumined by higher truth--with the bliss of these two spirits! Love, whether newly-born, or aroused from a death-like slumber, must always create a sunshine, filling the heart so full of radiance, that it overflows upon the outward world." (1461)

- Nature 2.0 is it as simple as Nature bad because it's "heathen"? Which character is most associated with nature in the novel? Pearl (see 1462 and the forest as her "playmate" and her petting a "wolf") And what does this child do to Hester? And see the reflected image of Pearl in a pool pointing her finger at Hester "its pointed finger, and imperious gesture" (1464) • Why does Pearl order Hester: "Come thou and take it up!" (1465)

- Romance, mystery, ambiguity: story of wolf and Pearl 1462; Dimmsdale on the scaffold; WHY INCLUDE THIS? WHY MAKE SOME THINGS AMBIGUOUS? Connect this to 1471 -- ambiguity -- people don't know what happened

- GROUP QUESTION What different meanings are ascribed to the letter "A"? Why? What does Hawthorne suggest about the meaning/perception of symbols (and meaning/perception in general?) by this? 1439, 1440

- Narrator again. He/she wonders why Dimmsdale wants to preach the Election day sermon "a more suitable mode and time of terminating his professional career" (1467). Why does the narrator call this desire "Sad" (1467)? What's sad about it?

- Why the marked change in Dimmsdale's perception of the setting ("The pathway among the woods seemed wilder") and in his actions ("he leaped across the plashy places) after his talk in the woods with Hester? (1468). And note he too experiences a "revolution" (1468). And what does he mean by the following: "Another man had returned out of the forest--a wiser one--with a knowledge of hidden mysteries which the simplicity of the former never could have reached. A bitter kind of knowledge that!" (1472). And finally, why have such a strong appetite ("he ate with ravenous appetite" [1472])?

- And speaking of changes, why the change in Dimmsdale's manner from before ("on the very proudest eminence of superiority" [1485]) to after his sermon?

- Note that Dimmsdale reaches the height of his profession: "Never, on New England soil had stood the man so honoured by his mortal brethren as the preacher!" (1486)

- Why does Chillingworth try to stop Dimmsdale: "Do not blacken your fame, and perish in dishonor! I can yet save you" (1487)?

- Our old friend "afflictions" returns (1489)

- How about a final question about the narrator? Okay. In the penultimate paragraph, the narrator writes

Earlier in life, Hester had vainly imagined that she herself might be the destined prophetess, but had long since recognised the impossibility that any mission of divine and mysterious truth should be confided to a woman stained with sin, bowed down with shame, or even burdened with a life-long sorrow. The angel and apostle of the coming revelation must be a woman, indeed, but lofty, pure, and beautiful, and wise; moreover, not through dusky grief, but the ethereal medium of joy; and showing how sacred love should make us happy, by the truest test of a life successful to such an end. (1493)

What does this show about the idea of "true womanhood" and the "office" of the scarlet letter?

- The novel as a critique of Puritanism.

- What is Hawthorne's opinion of science and emotion? Is it as simple as one is good and one is bad?

- What does this novel imply is the role of women in society? Is it hopeful? Resigned? Tragic?

- What is Pearl's function?

- What role does the Devil play in this novel?

- What does nature symbolize in SL ?

- What significance does the scaffold have in the essay?

- What do the images of the Other (native Americans, Europeans) mean? Why are they there? Native Americans occur several times throughout the novel -- and Chillingworth was captured by them a la' Mary Rowlandson. What's their symbolic function? What do Native Americans represent in the novel? Is this representation static?

- What role does the supernatural play in this novel? What is its purpose?

- What light does the "Customs House" shed on the novel? What is its purpose?

- Why is Hawthorne so often ambiguous with his descriptions?

- What is Chillingworth's role in the novel?

- Argue that either Chillingworth, Pearl, Dimmesdale, or Hester is the central character in the novel.

- Does Haw's use of light and dark imagery have any symbolic meaning?

- The Recognition: go over that chapter - 62-68 has many different meanings, irony of speech, foreshadowing, intellect v. feeling. (Heart). p 68

- Ambiguity -- irony? the double meaning of words when Hester and Dimmesdale speaks. I also think the ambiguity mirrors H's view of life: thus, who are we to judge anyone when we can't possible know all about them. It is also the crux of his story telling method: it is history? Is it "real" or "not real".

H. is of two minds in the story: thus his ambiguity. He can't say that adultery is ok -- Hester has to return and work out her penitence. But his ambiguity allows him to pose questions which are dangerous to offer in 1850: sexual freedom, slavery (91); relationships b/t husband and wives, social mores, the role of women ( Seneca Falls 1848) (201, 132) -- D. dies with a clean breast (Westmorland?) H. has to remain -- who has it worst? Also ties in with he supernatural -- why is it important to H.? shows ambiguity for one thing

-

Nature vs. Civilization "wild rose bush" 54, 89 Hes. talking going to Governor's Bill's house "backed by the sympathies of nature" (89); But is it as simple as Forest good, City bad? "A Forest Walk" 145 -- ambiguous because the forest both protects them, but it also keeps them outcasts.

Pearl 's function: 161, child of nature, but does nature really approve of H. and D.? Pearl , who's just been extravagantly described as a child of nature says what to Hester? (165) Pearl is the voice of honesty: instinct 149. Providential guidance.

The power of the forest 150 - D's is revealed as he really is. And for Dimmesdale, the Forest is a place of spiritual wandering and temptation in the wilderness cf. "The Minister in a Maze" 167+. But could the forest treat Hester and Pearl differently than Dimmesdale (**** on the woods "Here, seen only by his eyes, the scarlet letter need no burn into the bosom of the fallen woman!" (155))? Why (dichotomy of mind and soul)? Hester is identified with Wildness and sensuality 75, 78, 159

They plan their escape 156 (in the forest) but you cannot escape sin -- as P. (165) and C. 182 demonstrate.

- emotion vs. intellect 102, 118, 184 -- why does this seem so important to H.

Intellect v. emotion: D., after the forest, is operating on his emotions. After looking at the old sermon, composed with the bible etc. 173, he writes how? "with such an impulsive flow of thought and emotion" (175) and in the procession, 184 the "mind" is missing; he has become "spirit like" (184)

- role of women? D. to H "Think for me, Hester! Thou art strong. Resolve for me!" (155), 201, 134, 157

- Customs House

- What are some possible relationships b/t the CH and the SL: I had one professor (a different one from the one that told me Dimmesdale was the crucial character) tell me this was the most important part of the novel? 46

- Debate b/t "Actual and the Imagination" (46) recalls the emotion vs. intellect 102, 118, 184 -- why does this seem so important to H. Intellect v. emotion: D., after the forest, is operating on his emotions. After looking at the old sermon, composed with the bible etc. 173, he writes how? "with such an impulsive flow of thought and emotion" (175) and in the procession, 184 the "mind" is missing; he has become "spirit like" (184)

- The supernatural?

- Other meanings?

- The role of literature and the imagination -- connects nature to imagination (a la' a transcendentalist -- in fact, right after discussing transcendentalism addresses nature and imagination.

- Psychoanalytic

criticism: Ego (rational), Id (instinct), Superego (moral), Libido,

complexes, unconscious desires, sexual repression

- The "A" as fetish symbolizing both desire and repression

Feminist criticism

- Hester represents a dark heroine: both fallen, yet somehow transformed into an angel.

How are the other Hawthorne stories, "Young Goodman," "Minister’s," and "Rappinici," similar to Scarlet? For one, compare Hester to Beatrice -- how are they similar?

Critics have developed four basic approaches to the novel. Each deal with the problem of sin, which seems to be a central theme in the book.

- "Sin is permanently warping" coloring all aspects of life -- it spawns other sins ultimately leading to tragedy.

- Fortunate fall: without sin there would be no recognition of evil and thus no growth. Only by learning of sin -- and even committing sins, can we learn from it. This learning curve usually involves suffering and ultimately redemption

- Society itself is guilty: no sin has been committed because it is natural for two people to love one another. "Man is good; institutions are bad because they thwart nature"

- Psychological reading of SL -- sin "as an element which may . . . disturb . . . physic balance." -- the sin is important only insofar as the individual allows himself to be affected by it.

Works Cited

Reynolds, David S. Beneath the American Renaissance: The Subversive Imagination in the Age

of Emerson and Melville. Harvard UP: 1989. Print.

"Declaration of Sentiments." Antebellum American Culture. Ed. David Brion Davis. University Park,

Pennsylvania: Penn State UP, 1997. 91-93. Print.

![]()

Group Questions #1

Remember to include quotes and page numbers

- What is Hester like? What are her salient characteristics? What does the narrator admire in her character? What does the narrator condemn?

- What are Dimmesdale’s salient characteristics? What does the narrator admire in his character? What does the narrator condemn?

- What is Chillingworth’s background? How does it effect his character? What are his salient characteristics? What does the narrator admire in his character? What does the narrator condemn?

- Hester tells a group of Puritan elders "this badge hath taught me--it daily teaches me--it is teaching me at this moment--lessons whereof my child may be the wiser and better, albeit they can profit nothing to myself" (511). Given her experiences in this first assigned reading, what is Hester learning -- and what has Pearl learned?

Group Questions #2

Remember to include quotes and page numbers

- Dimmesdale and Chillingworth have a heated conversation on pages 525-27. How is Chillingworth characterized? What makes Dimmesdale so angry? Why the trait of "wonder" in Chillingworth's "ecstasy" (527)?

- Why include the second scaffold scene (534-537)? How is this similar to the first scene? How is it different? How does it contribute to our understanding of Dimmesdale, Hester, and Chillingworth? Why place this scene at this point in the novel?

- How do the readings on 1848 and on women's roles in 19th century America reflect upon the novel?

- The narrator has a one sentence paragraph: "The scarlet letter had not done its office" (541). OED the word office, and looking at the paragraphs before this line, what does it mean? What was the "office" of the SL, and why hadn't it "done" its work?

- How is Hester a feminist? Through Hester, does this book, ultimately, acknowledge the power or the weakness of women?

Group Questions #3

- Setting: How does the forest function in the story? How does the town function? What does Europe represent?

- What different meanings are ascribed to the letter "A"? Why? What does Hawthorne suggest about the meaning/perception of symbols (and meaning/perception/ambiguity in general?) by this?

- Why the marked change in Dimmsdale's perception of the setting ("The pathway among the woods seemed wilder") and in his actions ("he leaped across the plashy places) after his talk in the woods with Hester? (568). And note he too experiences a "revolution" (569). And what does he mean by the following: "Another man had returned out of the forest--a wiser one--with a knowledge of hidden mysteries which the simplicity of the former never could have reached. A bitter kind of knowledge that!" (572). And finally, why have such a strong appetite ("he ate with ravenous appetite" [573])?

- How about a final question about the narrator? Okay. In the penultimate paragraph, the narrator writes

How is this a comment on the idea of "true womanhood" and the "office" of the scarlet letter? And to answer this, you have to, of course, state what this comment is . . . .Earlier in life, Hester had vainly imagined that she herself might be the destined prophetess, but had long since recognised the impossibility that any mission of divine and mysterious truth should be confided to a woman stained with sin, bowed down with shame, or even burdened with a life-long sorrow. The angel and apostle of the coming revelation must be a woman, indeed, but lofty, pure, and beautiful, and wise; moreover, not through dusky grief, but the ethereal medium of joy; and showing how sacred love should make us happy, by the truest test of a life successful to such an end. (593)

- In an 1844 notebook entry, Hawthorne wrote the following idea for a story: "Sketch of a person, who, by strength of character, or assistant circumstances, has reduced another to absolute slavery and dependence on him. Then show, that the person who appears to be the master, must in inevitably be at least as much a slave, if not more, than the other. All slavery is reciprocal" (32). How is this idea born out in the novel?

- List and explain two connections between the "Custom House" and The Scarlet Letter.

![]()

Click to enlarge Hawthorne's hand written chapter listing.

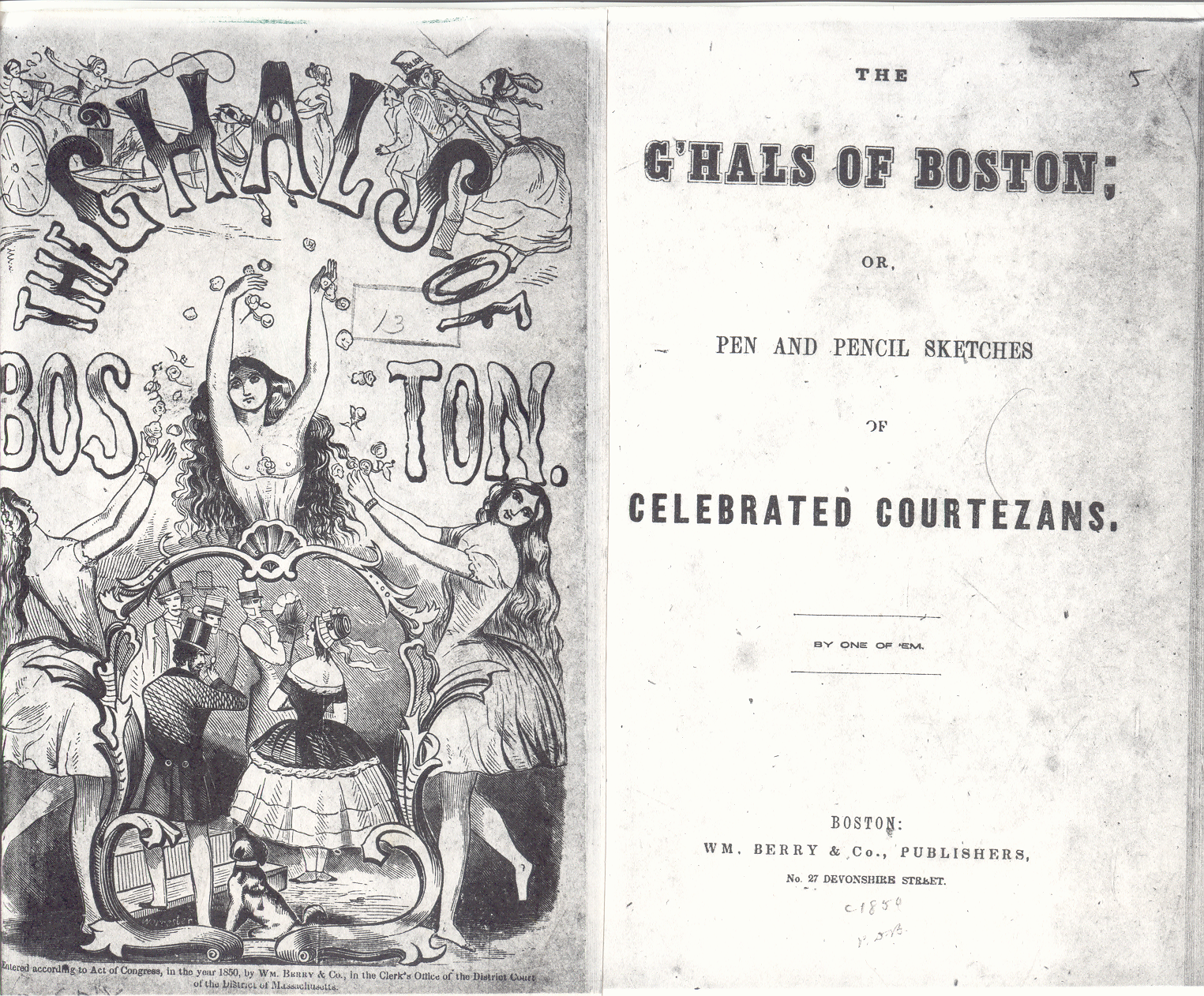

I thought there was no sex in the 19th century? This illustration from

a sensational novel shows that tales of seduction -- a la' Scarlet Letter -- were common currency in popular literature.

And in the same year, 1850, (the year Scarlet was published) appeared the following.

Together, these texts and illustrations show that many antebellum readers were eager for tales of fallen women and debauchery.

Yet not all readers shared this fascination. Some reviews of Scarlet warned against its subject matter. Arthur Cleveland Coxe, writing in the January 1851 edition of Church Review, wonders -- and then answers in a negative fashion --

Why has our author selected such a theme? Why, amid all the suggestive incidents of life in a wilderness; of a retreat from civilization to which, in every individual case, a thousand circumstances must have concurred to reconcile human nature with estrangement from home and country; or amid the historical connections of our history with Jesuit adventure, savage invasion, regicide outlawry, and French aggression, should the taste of Mr. Hawthorne have preferred as the proper material for romance, the nauseous amour of a Puritan pastor, with a frail creature of his charge, whose mind is represented as far more debauched than her body? Is it, in short, because a running underside of filth has become as requisite to a romance, as death in the fifth act to a tragedy? Is the French era actually begun in our literature? And is the flesh, as well as the world and the devil, to be henceforth dished up in fashionable novels, and discussed at parties, by spinsters and their beaux, with as unconcealed a relish as they give to the vanilla in their ice cream? We would be slow to believe it, and we hope our author would not willingly have it so, yet we honestly believe that "the Scarlet Letter" has already done not a little to degrade our literature, and to encourage social licentiousness: it has started other pens on like enterprises, and has loosed the restraint of many tongues, that have made it an apology for "the evil communications which corrupt good manners." We are painfully tempted to believe that it is a book made for the market, and that the market has made it merchantable, as they do game, by letting everybody understand that the commodity is in high condition, and smells strongly of incipient putrefaction. (258-59)

It's clear that for Coxe, the subject matter itself outweighs any moral concern.

Coxe, Arthur Cleveland. "The Writings of Hawthorne." Church Review. January 1851. Rprt. in The Scarlet Letter and other Writings. Ed. Leland S. Person. New York: Norton, 2005. 254-263. Print.

Lady Madonna . . .(as the Beatles would say)

"I can feel your halo, halo, halo" (as Beyonce would say)

|

Carlo Crivelli 1470 |

Sandro Botticelli 1465-67 |

|

Jan Gossaert (1520-1530) |

All images from wikipedia.org |

![]()

Hawthorne in Salem is probably the best starting point for Hawthorniacs on the web.

Interesting online museum exhibit of a "Newspaper" that Hawthorne wrote as a child.

Song for Young Goodman Brown: obvious, but effective.

![]()

On the symbolism of hearts in 19th culture: "There was no question that literary domesticity was an office enveloped in a mystique and trappings and characterized by a perspective and a language different from those of a male creator of culture. The heart was the symbol of woman, of woman's traditional being, of woman's involuntary life, of woman's nurturing, caring for, and living for others. The heart's record was the woman's revealed record of her life of domesticity, the only life she could have. In her mind the woman is not the emperor of culture. She is, by default, the empress of heart." (Kelly 221)

"No belief was more highly cherished and more eloquently proclaimed than that of the inherent nobility of the human heart" (Brown 143)

Brown, Herbert Ross. The Sentimental Novel in America 1789-1860. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 1940. Print.

Kelly, Mary. Private Woman, Public Stage: Literary Domesticity in Nineteenth Century America. New York: OUP, 1984. Print.

© 2009 David Bordelon