Course Links

Lesson Plans

Course Documents

Links

Secondary Sources

Quick Links

Library Links

Citing Sources

|

Terms | Life | Times | Class Discussion | Group Questions | Links | Pictures | Quotes from Critics

Image from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Black-white_photograph_of_Emily_Dickinson2.jpg

![]()

Lyric: Short, personal poems which present a unified examination of a particular topic.

anaphora A rhetorical figure of repetition in which the same word or phrase is repeated in (and usually at the beginning of) successive lines, clauses, or sentences. Found very often in both verse and prose, it was a device favoured by Dickens and used frequently in the free verse of Walt Whitman . These lines by Emily Dickinson illustrate the device:

Mine--by the Right of the White Election!

Mine--by the Royal Seal!

Mine--by the Sign in the Scarlet prison

Bars--cannot conceal!

Adjective : anaphoral or anaphoric . See also epistrophe .

"anaphora." The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Ed. Chris Baldick. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Web. 21 January 2010.

![]()

Life

Growing up amidst the second Great Awakening – a time of religious

fervor swept through Amherst – when most of her friends “converted.”

She resisted this. That said, her work is infused with biblical

references.

Regarding her personality, there’s long been the idea that she lived as a recluse, sheltered from the world.

Yes and no.

Yes, she spent the second half of her life primarily with family and primarily in her room, but this was a gradual process. Her surviving family, Austin and Lavinia, specifically noted that Emily was no different than others.

No to the sheltered from the world. She read deeply, and was intimately aware of sex, the war, social injustice.

To take the first example, her married brother (Austin) carried on a prolonged affair with a married women for years. The daughter recalls that this involved being locked up in a room with her all afternoon with no one allowed to disturb them.

I say this to show that while her circle was close, it encompassed much experience.

She lived only 56 years – but wrote around 1800 poems, which she collected into bundles ('fascicles'), that were discovered at her death by her sister, Lavinia, and were first published in 1891. In 1955, Edward Johnson published the first scholarly edition – which retained Dickinson’s idiosyncratic capitalization, syntax, and punctuation.

Only 10 her poems were published in her lifetime, but many of them were sent in letters.

"The issues of the Springfield Republican included here contain poems composed by Dickinson or War news important to Dickinson. The issues which include her poems are those of May 4, 1861 with "May Wine" ("I taste a liquor never brewed -"); March 1, 1862 with "The Sleeping" ("Safe in their Alabaster Chambers -"); March 30, 1864 with "Sunset" ("Blazing in Gold, and quenching in Purple"); and March 9, 1864 with "Flowers" ("Flowers - Well - if anybody"). Also included with these issues are articles that directly surround her poems and any articles with Civil War news. Lundin notes that some of the poems came from letters to Bowles and that they "were published without her permission" (105).

A fine short biography (and general commentary on her poetic method) by Ruth Miller (a major Dickinson scholar) can be accessed here.

More biography: several years ago PBS sponsored a series of hour long television programs on American poets, including Emily Dickinson. Like the Whitman video, it's an excellent introduction to her life, the time she lived in, and her work.

The video is available at this link . Scroll down towards the bottom of the page to access it.

Use the following as a username and password

Username: occ.chat@yahoo.com

Password: poetry

![]()

On her love of words – and punctuation

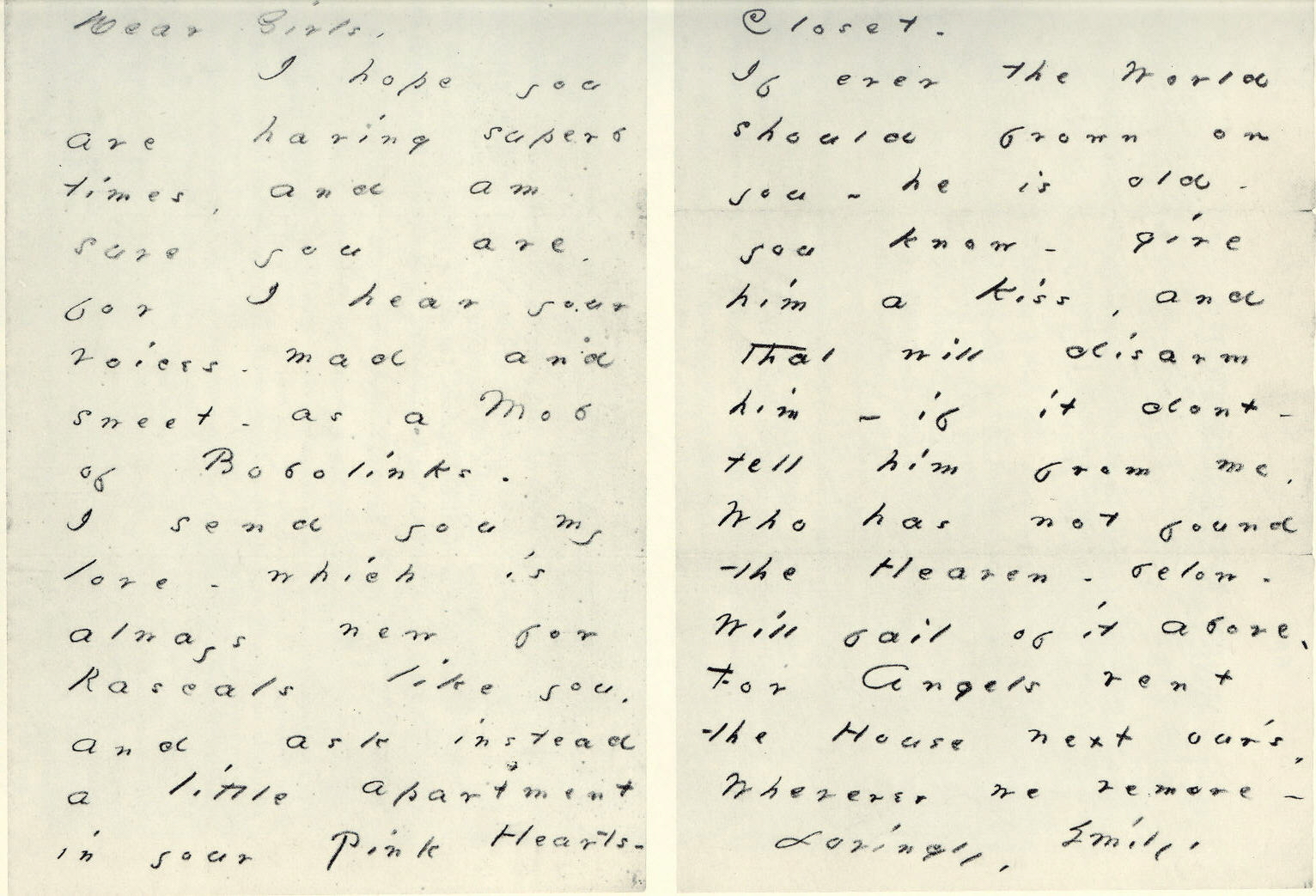

Letter to friend

“We used to think, Joseph, when I was an unsifted girl and you so scholarly that words were cheap & weak. Now I don’t know of anything so mighty. There are [those] to which I lift my hat when I see them sitting princelike among their peers on the page. Sometimes I write one, and look at his outlines till he glows as no sapphire” (qtd. In Sewall 423)

And consider these pages from the composition textbook she used at Mount Holyoke Seminary.

In an early valentine letter, after comparing herself to the biblical Judith, she writes

“That’s what they call a metaphor in our country. Don’t be afraid of it, sir, it won’t bite.”

And the reason she needs to resort to metaphor? Similar to Thoreau “But the world is sleeping in ignorance and error, sir, and we must be crowing cocks, and singing larks, and a rising sun to awake her; or else we’ll pull society up to the roots, and plant it in a different place. We’ll build Alms-houses, and transcendental State prisons, and scaffolds – we will blow out the sun, and the moon, and encourage invention. Alpha shall kiss Omega – we will ride up the hill of glory – Hallelujah, all hail!” (qtd. In Sewall 420)

Dickinson's obiturary -- written by her sister in law, Susan Dickinson, published in the Springfield Republican (May 18, 1886)

![]()

Times

While writing during a time of national turmoil -- abolitionism, war, etc -- her poems seem to ignore the world around her. Odd, considering how active her father and brother were in the affairs of their times.

Given her style, be on the look out for oblique references to ideas of the time, including religion, slavery, etc.

While Dickinson's fascination with funeral matters is at odds with our current fear and revulsion to dead bodies, consider the image below.

Unfortunately, this girl is not sleeping. This is an example of a common type of photography during this period: a memento mori. These pictures of the recently deceased were not considered ghoulish; instead, they were a way of remembering (memento) the dead (mori). In an age of high childhood mortality, they were often the subjects.

Unfortunately, this girl is not sleeping. This is an example of a common type of photography during this period: a memento mori. These pictures of the recently deceased were not considered ghoulish; instead, they were a way of remembering (memento) the dead (mori). In an age of high childhood mortality, they were often the subjects.

<From http://brightbytes.com/collection/memento.html>

Consider, as well, the contemporary comments on death copied below.

![]()

Dily Richards, writing from Mason, Tennessee in 1855, delineates a roll-call of the dead to his brother-in-law: "Your Brother Jon is ded [;] he Died the 11 of Sptenber last I am her by Alone. . . .Jon dident live but five days[.] [S]uppose he died with the fluks . . . . Ammy Richards is dead[,] Rebecah Richards is dead [,] Henison is Dead[.] [M]y yongest child About Twenty too years old an my our step son died in Mexico[.] Burrels oldest son is dead [;] he was About twenty years old[.][H]is dagter is dead[;] she was About five years old" (Saum 82)

![]()

A Georgian girl, from a school composition titled "Things that I Love," penned a rhapsody to graveyards which mirrors Nell's passion: "I love to walk in the graveyard, and read the inscriptions on the tombstones, the weeping willows fall so gracefully over the silent dead; here and there you may see a rosebush, or a bed of violets, planted and trained by some gentle hand over a dead friend" (Saum 91)

![]()

Godey's Lady's Book vol. 26, 1843 boasts two poems entitled "The Dying Girl" Henry S. Hagert, and Mrs. John K. Lasky, as well as "The Memory of the Departed" "The Young Southern Widow" "The Mother's Lament" (about the death of a child), "The Trial of the Dead" "The Angel's Visits" ("And the Angel soars to his home on high,/While faith reveals, to the mother's eye,/ That he bears her sweet child to heaven!" Mrs. S. J. Hale), "The Mourner" ("She sleeps -- `the long and dreamless sleep' -- that voice is silent now,/ The seal is on her clay-cold lip, the death-dew on her brow.). And even a title as seemingly as carefree and lively as "To a Child at Play" ends, after picturing the "sweet frolic" of a "fair and lovely boy," ends with "And, when thy life is o'er,/ Translate thee to that `better land'/ Where sin and sorrow come not, and/ Where death shall be no more." (127) Lewis J. Cist.

Works Cited

Saum, Lewis O. The Popular Mood of Pre-Civil War America. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press,

1980.

![]()

Questions to mull over as you interpret the Work

General Approach to Dickinson's Poetry

Dickinson's work is very indivdual -- yet open to all who take the time to interpret it. Below find some general guidelines that should help you when reading her poetry

From http://guweb2.gonzaga.edu/faculty/campbell/enl311/dickpoems.html

1.

Speaker. Who is the speaker? What person (first, second, third) is ED

speaking in? If it is the first person plural, with whom has she

aligned herself? To whom is the poem addressed?

2. Setting or Situation. What is the setting? Real? Abstract? What

about the situation? Is there action in the poem? What is it?

3. What are the verbs? What is their tense? Their mood (indicative,

subjunctive, interrogative)? In what ways does their syntax vary from

what you expect? Are any of them archaic or unusual?

4. What is the form of the poem? Closed? Open? What is the meter? the

rhyme scheme? Where does ED depart from these patterns and forms? Why?

Dickinson is noted for her use of special kinds of rhyme. Where does she use the following, and for what effect?

a. slant rhyme: a kind of consonance (relation between words in which the final consonants in the stressed syllables agree but the vowels that precede them differ: add/read, up/step, peer/pare, while/hill).

b. eye rhyme: rhyme that appears correct from the spelling but is not so from the pronunciation, such as watch/match, love/move, through/enough.

c. true rhyme: identity of terminal sound between accented syllables, usually occupying corresponding positions in two or more lines of verse. The correspondence of sound is based on the vowels and succeeding consonants of the accented syllables, which must, for a true rhyme, be preceded by different consonants. Thus "fan" and "ran" constitute a true rhyme because the vowel and succeeding consonant sounds ("an") are the same but the preceding consonant sounds are different.

6. What elements are repeated? Inverted? Why? What instances of repetition does she use? What is the effect of the repetition?

7. What figures of speech does the poem contain? metaphor? metonymy? synecdoche? personification? extended metaphor? What kind of figure does she use as a comparison (vehicle)? Where has she used this before and with what kinds of meaning or resonance?

8. What kinds of images does she use? olfactory? tactile? visual? auditory? thermal? Characteristic Dickinson images include patterns of light/dark, bee/flower, mind/body, life/death. Do these occur here? In what combination?

9. Does the poem have an effective, striking, or climactic moment? Does it come to some kind of resolution? What kind? What recognition does the speaker's persona achieve, or does the poem chronicle simple description and observation?

10. Tone. What is the tone of the whole? Solemn? Playful? Irreverent? Mournful? Objective? What is Dickinson trying to convey?

11. Tradition. In what ways does she allude to other works or poetic traditions? In what ways might this poem be an "answer" to another author?

12. Rhetorical figures. Where does Dickinson use paradox? hyperbole? anaphora? apostrophe? litotes? Why does she use them?

13. Language. Note any words that are used in an archaic, special, or unusual way, especially words of three syllables or more. (These are less common in Dickinson's work than one- and two-syllable words.) Look them up in the dictionary, being careful to note obsolete or secondary meanings as well as primary ones.

![]()

Group Questions #1

Need quotes and line/page numbers for each answer.

- Using both sets up poems, (from last class and from today), group them thematically – i.e. these poems are “about” ____, these “about” ____.

- Once they are grouped, choose one poem from each group and 1) explain how/why it is about ________, and 2) explain what the poem is saying about _____.

Group Questions #2

Need quotes and line/page numbers for each answer.

- No mystery on theme here: death. But what is she getting at? Can you group these poems of death into more specific categories? How do they seem related?

- One critic notes that “At certain moments, death can become for Dickinson a welcome relief from pain, thought, and instability” (Ferlazzo). How is this illustrated in her poetry?

- On a different note, Emily herself wrote to Higginson that "I sing, as the Boy does by the Burying Ground--because I am afraid." If her singing is her poetry, how does this idea of “whistling past the graveyard” (the saying she alluded to in her letter to Higginson, and a saying which means maintaining your courage in the face of fear) illustrated in her poetry? How does writing about death become an act of courage?

For an illuminating contrast see Sigourney's "Death of an Infant" in our textbook. It's a fine representative of a more typical poem about death from the period.

- Why is Dickinson so celebrated as a poet? Is this acclaim warranted? Why or why not?

![]()

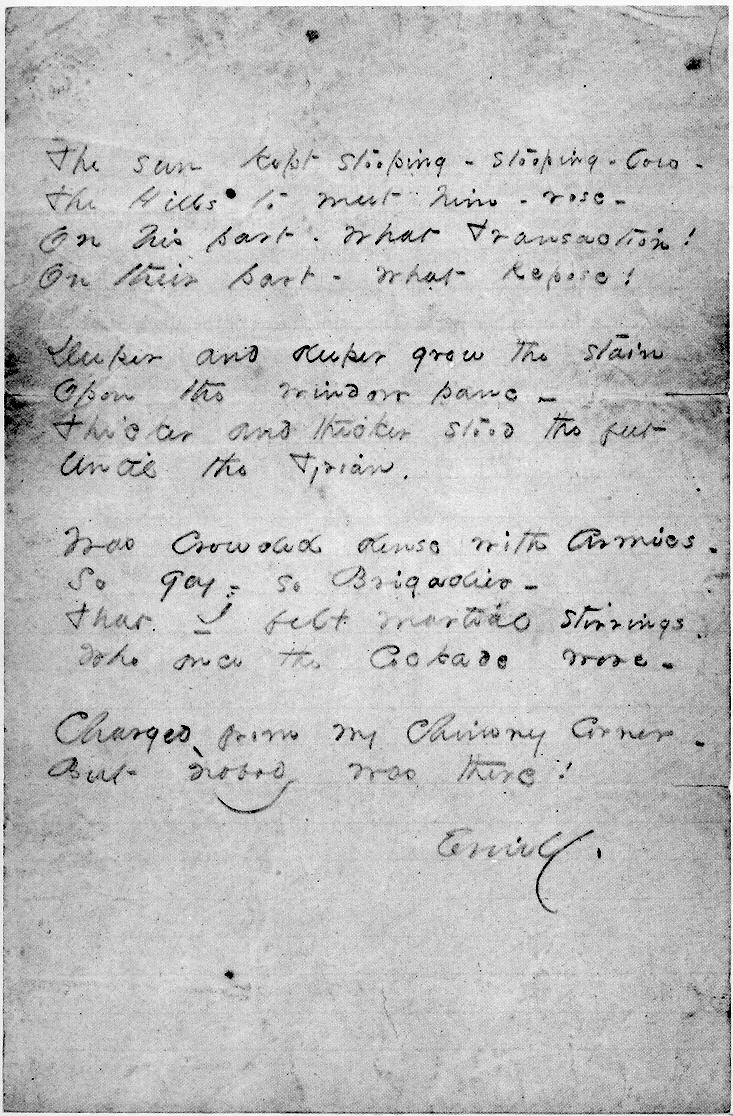

Manuscript of Dickinson's poem "The Sun Kept Stooping -- Stooping -- Low" #152

(From American Literary Autographs)

![]()

2013 update: Harvard and Amherst libraries, which hold the majority of Dickinson manuscripts and emphemra, have "reconciled their differences" and worked together to set up an Emily Dickinson Archive. This is the place to go for all things Dickinson.

Works in progress: a page devoted to manuscript versions of her poetry -- particularly those in our own Norton Anthology.

A great place to start background research on Dickinson is to use the Dickinson Electronic Archives, an online compendium of manuscripts, essays, and other information on Dickinson and her times.

Interesting discussion of "Because I Could Not Stop For Death" from Studio 360. Worth a listen.

1891 essay by Thomas Wentworth Higginson discussing his correspondence with Dickinson. Wonderful evocation of her life from someone who knew her.

![]()

© 2009 David Bordelon