Lesson Plans

Course Links

Lesson Plans

Course Documents Links

Secondary Sources

Quick Links

Library Links

Citing Sources

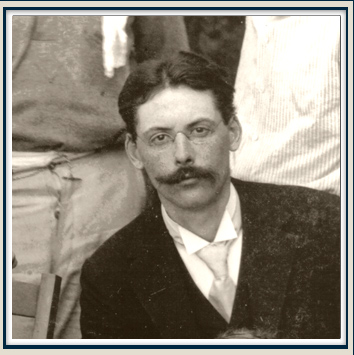

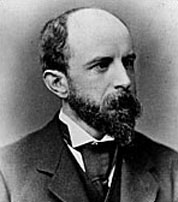

E. A. Robinson (circa 1890s-1920s), Henry Adams (1907,1918)

|

E. A. Robinson |

Henry Adams |

Terms | Life | Times | Class Discussion | Group Questions | Pictures

Link to "Cassandra" and "Clerks"

Terms to Know

Existentialism: "European philosophic movement with various schools or attitudes of different eras, including the Christian concepts of Kierkegaard and Maritain, but affecting American literature primarily in terms of an atheistic view shared with or influenced by Sartre and Camus. Holding that there are no accepted bases to explain the mysteries of human existence and that the individual must develop his being free of society, existentialism contends that solitariness makes the right condition for freedom of choice. However, it also brings anguish to the individual as he recognizes the futility of attempting to treat the paradoxes of a meaningless universe and an absurd world and to achieve self-mastery in an atmosphere of entire freedom. Such views and such a sense of metaphysical isolation in the consideration of the individual in the present moment are found in the fiction of Saul Bellow, Paul Bowles, Ralph Ellison, William Styron, and Richard Wright. Frequently using the monologue to show the protagonist's growing consciousness of the human condition, since thought rather than action is dominant in existential fiction, their novels deal with depersonalization, alienation from society and belief in divinity, and an individual search for identity.

"Existentialism." The Oxford Companion to American Literature. James D. Hart, ed., rev. Phillip W. Leininger. Oxford University Press 1995. Oxford Reference Online. Web. 28 February 2009.

"Sartrean [from Jean-Paul Satre] existentialism, as distinct from the Christian existentialism derived from [Soren] Kierkegaard, is an atheist philosophy of human freedom conceived in terms of individual responsibility and authenticity. Its fundamental premiss that ‘existence precedes essence’, implies that we as human beings have no given essence or nature but must forge our own values and meanings in an inherently meaningless or absurd world of existence. Obliged to make our own choices, we can either confront the anguish (or Angst ) of this responsibility, or evade it by claiming obedience to some determining convention or duty, thus acting in ‘bad faith’. Paradoxically, we are ‘condemned to be free’. Similar themes can be found in the novels and essays of Camus; both authors felt that the absurdity of existence could be redeemed through the individual's decision to become engagé (‘committed’) within social and political causes opposing fascism and imperialism. Some of the concerns of French existentialism are echoed in English in Thom Gunn's early collection of poems. The Sense of Movement ( 1957 ), and in the fiction of Iris Murdoch and John Fowles . See also phenomenology . For an introductory anthology, consult Paul S. Macdonald (ed.), The Existentialist Reader ( 2001 )."

"existentialism" The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms . Chris Baldick. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford Reference Online . Oxford University Press. Web. 28 February 2009.

Sonnet: A lyric poem comprising fourteen rhyming lines of equal length: iambic pentameters in English, alexandrines in French, hendecasyllables in Italian. The rhyme schemes of the sonnet follow two basic patterns.

1. The Italian sonnet (also called the Petrarchan sonnet after the most influential of the Italian sonneteers) comprises an 8 line ‘octave’ of two quatrains , rhymed abbaabba, followed by a 6 line ‘sestet’ usually rhymed cdecde or cdcdcd. The transition from octave to sestet usually coincides with a ‘turn’ (Italian, volta) in the argument or mood of the poem. In a variant form used by the English poet John Milton , however, the ‘turn’ is delayed to a later position around the tenth line. Some later poets—notably William Wordsworth —have employed this feature of the ‘Miltonic sonnet’ while relaxing the rhyme scheme of the octave to abbaacca. The Italian pattern has remained the most widely used in English and other languages.

2. The English sonnet (also called the Shakespearean sonnet after its foremost practitioner) comprises three quatrains and a final couplet, rhyming ababcdcdefefgg. An important variant of this is the Spenserian sonnet (introduced by the Elizabethan poet Edmund Spenser ), which links the three quatrains by rhyme, in the sequence ababbabccdcdee. In either form, the ‘turn’ comes with the final couplet, which may sometimes achieve the neatness of an epigram . Originating in Italy, the sonnet was established by Petrarch in the 14th century as a major form of love poetry, and came to be adopted in Spain, France, and England in the 16th century, and in Germany in the 17th. The standard subject matter of early sonnets was the torments of sexual love (usually within a courtly love convention), but in the 17th century John Donne extended the sonnet's scope to religion, while Milton extended it to politics. Although largely neglected in the 18th century, the sonnet was revived in the 19th by Wordsworth, Keats, and Baudelaire, and is still widely used. Some poets have written connected series of sonnets, known as sonnet sequences or sonnet cycles: of these, the outstanding English examples are Sir Philip Sidney's Astrophel and Stella (1591), Spenser's Amoretti (1595), and Shakespeare's Sonnets (1609); later examples include Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Sonnets from the Portuguese (1850) and W. H. Auden's ‘In Time of War’ (1939). A group of sonnets formally linked by repeated lines is known as a crown of sonnets. Irregular variations on the sonnet form have included the 12 line sonnet sometimes used by Elizabethan poets, G. M. Hopkins's curtal sonnets of 101/2 lines, and the 16 line sonnets of George Meredith's sequence Modern Love (1862). For an extended introductory account, consult John Fuller, The Sonnet (1972).

http://www.sonnets.org Sonnet Central: archive of sonnets with historical notes and links.

"sonnet." The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Chris Baldick. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Ocean County College. 4 March 2009

The Life

Two transitional figures here. Both Robinson and Adams straddle the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, looking backwards and forwards in their aesthetic and world vision. In these writers we see both the concern with structure, form, and propriety that mark late victorian America, yet we also see these ideas challenged, tested, and probed. And here (and in Chopin's The Awakening) we see the angst that becomes a primary feature of twentieth century literature.

1916 Interview with Robinson

Edwin Arlington Robinson Defines Poetry; A Language, Says Well-Known Poet, That Tells Us Through More or Less Emotional Reaction Something Which Cannot Be Said

By Joyce Kilmer.. New York Times (1857-Current file). New York, N.Y.: Apr 9, 1916. p. SM12 (1 page) Article image - PDF (205 K)

Below find Robinson's "The Clerks," a particularly good example of his early work (published in his first, self-published book The Torrent and the Night Before [1896])

Shades of Bartleby the Scrivner . . . .

This is contrasted with the works of much more popular writers which illustrate what American poetry was like in late 19th century America.

John Bannister Taub Memory I go not to the grave to weep, We gathered it as, day by day, A Blackberry Bush Behold, above the hidden root, |

Richard Hovey America We came to birth in battle; when we pass, October, 1898 |

The poems above are explained, in part, by the reigning poetic aesthetic, exemplified in The Fireside Encyclopedia of Poetry: Comprising the Best Poems of the Most Famous Writers, English and American Edited by Henry T. Coates, published in 1895 and going through 34 editions. It claimed to "be a welcome companion at every FIRESIDE; and . . . while representing all that is best and brightest in our poetic literature, should contain nothing that would tend to undermine any one's faith or destroy a single virtuous impulse" (qtd in Gruesz 53).

As noted in the short excerpt on his life, the times, they are a'changing.

This transition is best illustrated in the shift from an antebellum agrarian to a post-war industrial culture. Census data show that agricultural work, the archetypal occupation of Americans, declined throughout this period, from 50.1 percent of the workforce in 1880 to 31.6 percent by 1910 (Shifflett 54). This decline, and a concomitant rise in industrial employment, brought about a new, more urban middle class and their values of piety and provincialism, diligence and optimism. Yet this shift in the cultural dynamic from rural to urban was challenged. Throughout the period, questions about American identity lingered. While most recognized and embraced the prevailing middle class ethos, some, confronted with the reality of an ascendant urban bourgeois, waxed nostalgic about a mythic America of rugged individualists plowing their own homesteads. Others, chafing under the prescriptive social rules and boundaries, objected to the conventionalism of middle class values. Ultimately, however, the middle class, as the historian Thomas Schlereth argues, "controlled the country's political, social, and cultural agendas" (xiii).

Religion, as it had from the colonial period, dominated the cultural and intellectual mindscape of Victorian Americans. Many were swept up by the fervor of the Third Great Awakening (1860s through 1900s), a time of revivalism and expanding church membership. Yet for others, particularly towards the end of the century, science, and especially Darwinism, weakened the hold of religion on their lives. This seeming dichotomy of embracing and eschewing religion is aptly illustrated by the recollections of two Maryland residents whose age, gender, and class set out the markers of this split in spiritual attitudes. The author Lizette Reese, recalling her middle class youth in the late 1860s and 1870s, wrote that it "was the age of faith. We were as sure of God as we were of the sun" (5). In contrast, recalling his upper class youth in the 1890s, the literary critic Henry Seidel Canby wrote that the "inner significance" of religion "was lost" (130-31). You'll find that most writers we'll be reading sympathize with Canby.

Robinson's Poetry

- How does Robinson feel about the speakers and characters in his poems? Does the treat them condescendingly?

- David Perkins suggests "If a formula could be given for a typical poem of Robinson, it would include the following elements: characterization; indirect and allusive narration; contemporary setting and recognition of the impingement of setting on individual lives; psychological realism and interest in exploring the tangles of human feelings and relationships; an onlooker or observer as speaker, making the poems impersonal and objective with respect to Robinson himself; a penchant for the humorous point of view combined with an awareness that life is more essentially tragic; a language that is colloquial, sinewy, and subtle as it conveys twists of implication in continually active thinking; a mindfulness of the difficulty of moral judgment but also a concern for it." Can we find these traits in his poetry?

- John Lucas writes that Robinson "is spokesman for the inarticulate, for those who, whatever the reason, have been forced into incommunicable loneliness." How so? How does he speak for the lonely? Is it just because so many of his characters are lonely?

- "There is more in every person's soul than we think. Even the happy mortals we term ordinary or commonplace act their own mental tragedies and live a far deeper and wider life than we are inclined to believe possible in the light of our prejudices." (qtd. in Blumenthal "Ambivalence") 1894 letter from Robinson

- In a review of the Torrent and the Night Before, Harry Thurston Peck "found many of the poems too somber for his liking and said that Robinson's "humour is of a grim sort, and the world is not beautiful to him, but a prison-house." In response to that comment Robinson wrote a letter of rebuttal, published in the March 1897 Bookman, which has become as well known a critical statement as he was ever to make: "I am sorry that I have painted myself in such lugubrious colours. The world is not a prison house, but a kind of spiritual kindergarten, where millions of bewildered infants are trying to spell God with the wrong blocks" (Joyner). How is this seen in his poetry? Especially the idea of god?

Richard Cory"

- Who's speaking in this poem?

- How can you tell what kind of people they are?

- what lines words in the poem suggest that Richard was rich? Which suggest that he was upper class?

- What is he contrasting here?

- What is ironic about this poem?

"Luke Havergal"

- Who's the speaker in this poem?

- What's the situation being presented?

- What images of death are in this poem?

- Who's coming out of the grave? What's the person want?

"Miniver Cheevy"

- How is Miniver connected to Tom Sawyer?

- Intimations of capitalism?

"Mr. Flood's Party"

- Town v. woods?

- Describe Flood's personality?

- Any clues about how/why he's reached this state?

- Why a party?

"Clerks"

- Which words pick up on time?

- What does he mean by "clerks of Time"?

- Thoreau, in Walden, describes most Americans as leading a life of "quiet desperation." How does this poem evoke the same ideas?

- On the other hand, is he necessarily criticizing them?

- This is a sonnet: is it a Shakespearean or an Italian sonnet? How would knowing the form of the poem make it easier to understand?

- How could this poem connect to "Richard Cory"?

"Cassandra"

- Who's Cassandra? How effective is the analogy?

- What becomes the Trojan horse?

- How does he make money into a religion?

- Why add the "Eagle" (line 29)?

- What does the final stanza show? How effective is it?

- Is this poem still relevant?

"The Virgin and the Dynamo"

- How is this literature and not history?

- Why discuss yourself in the third person? (This is, after all, taken from The Autobiography of Henry Adams).What does this allow him?

- How effective is the analogy Virgin=19th century, Dynamo=20th century?

- Which does Adams suggest is better? Virgin or dynamo?

- Do you see this idea of the Virgin or dynamo in Robinson's work?

- What does Adams mean by his distinction between Venus and the Virgin in America? Why does he say it doesn't exist as a force in America (354,355)?

- What does Adam suggest about the role/place of women in American culture?

- What does Adam suggest is the role of the artist/writer in America ?

- Adams as post modernist: "He had even published a dozen volumes of American history for no other purpose than to satisfy himself whether, by severest process of stating, with the least possible comment, such facts as seemed sure, in such order as seemed rigorously consequent, he could fix for a familiar moment a necessary sequence of human movement. The result had satisfied him as little as at Harvard College . Where he saw sequence, other men saw something quite different, and no one saw the same unit of measure" (353). What does this quote suggest about reality?

- David Perkins suggests "If a formula could be given for a typical poem of Robinson, it would include the following elements: characterization; indirect and allusive narration; contemporary setting and recognition of the impingement of setting on individual lives; psychological realism and interest in exploring the tangles of human feelings and relationships; an onlooker or observer as speaker, making the poems impersonal and objective with respect to Robinson himself; a penchant for the humorous point of view combined with an awareness that life is more essentially tragic; a language that is colloquial, sinewy, and subtle as it conveys twists of implication in continually active thinking; a mindfulness of the difficulty of moral judgment but also a concern for it." Can we find these traits in his poetry?

- Robinson described poetry as "a language which tells us, through a more or less emotional experience, something that cannot be said." (qtd. in Joyner) Though it can't be said/articulated, doesn't mean it's not revealed. What's revealed in "Mr. Flood's Party"?

- How could "Clerks" and "Cassandra" be read as a critique of capitalism?

Pictures, Pictures, Pictures

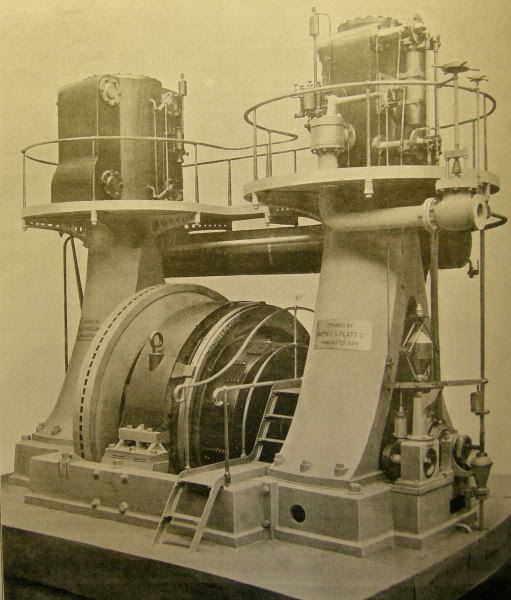

A dynamo from the 1900 Paris exhibition

Image from http://www.practicalmachinist.com/vb/showthread.php?p=926651

© David Bordelon 2009