Lesson Plans

Course Links

Lesson Plans

Course Documents Links

Secondary Sources

Quick Links

Library Links

Citing Sources

"The Snows of Kilimanjaro"

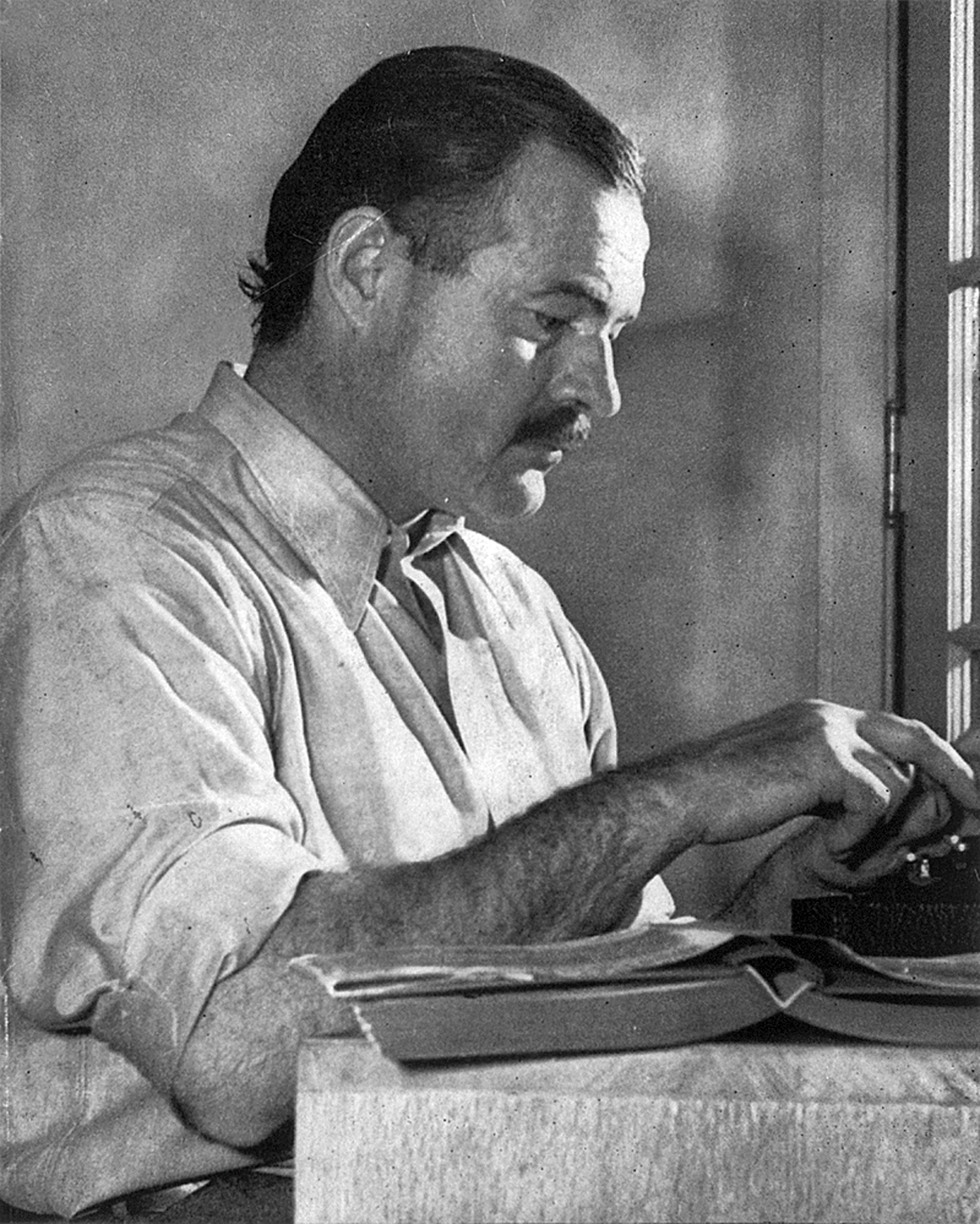

Ernest Hemingway

(1936-1938)

Image from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:ErnestHemingway.jpg

Link to stories from In Our Time (or in our time as it was first published). Print and read.

Terms | Life | Times | Class Discussion | Group Questions | Links | Pictures | Quotes from Critics

Terms to KnowSmyrna:

"In September of 1922, Mustapha Kemal (Ataturk), the victorious

revolutionary leader of Turkey, led his troops into Smyrna (now Izmir)

a predominantly Christian city, as a flotilla of 27 Allied warships

-including 3 American destroyers- looked on. The Turks soon proceeded

to indulge in an orgy of pillage, rape and slaughter that the western

powers anxious to protect their oil and trade interests in Turkey,

condoned by their silence and refusal to intervene. Turkish forces then

set fire to the legendary city and totally destroyed it. There followed

a massive cover-up by tacit agreement of the Western Allies. By 1923

Smyrna's demise was all but expunged from historical memory."

from http://www.greecetravel.com/smyrna/

For a longer article, see CATASTROPHE AT SMYRNA.By: Stewart, Matthew; History Today, Jul2004, Vol. 54 Issue 7, p. 27, 7p,

"The lost generation":

name applied to the disillusioned intellectuals and aesthetes of the

years following World War I, who rebelled against former ideals and

values but could replace them only by despair or a cynical hedonism.

The remark of Gertrude Stein, "You are all a lost generation ,"

addressed to Hemingway, was used as a preface to the latter's novel The Sun Also Rises ,

which brilliantly describes an expatriate group typical of the " lost

generation ." Other expatriate American authors of the period to whom

the term is generally applied include Malcolm Cowley, E. E. Cummings,

F. Scott Fitzgerald, Archibald MacLeish, and Ezra Pound.

"Lost generation." The Concise Oxford Companion to American Literature . James D. Hart. Oxford University Press, 1986. Oxford Reference Online . Oxford University Press. Ocean County College. 16 March 2009

See also

The Lost Generation' and 'Modern Life': Myth and Discourse for an American 1920s .

Marc Dolan. Modern Lives: A Cultural Re-Reading of "The Lost

Generation,". West Lafayette, Ind.: Purdue University Press, 1996. Rpt. in Twentieth-Century Literary Criticism .

Ed. Thomas J. Schoenberg and Lawrence J. Trudeau. Vol. 178.

Detroit: Gale, 2006. p9-47. From Literature Resource Center .

stream of consciousness: The continuous flow of sense-perceptions, thoughts, feelings, and memories in the human mind; or a literary method of representing such a blending of mental processes in fictional characters, usually in an unpunctuated or disjointed form of interior monologue . The term is often used as a synonym for interior monologue, but they can also be distinguished, in two ways. In the first (psychological) sense, the stream of consciousness is the subject-matter while interior monologue is the technique for presenting it; thus Marcel Proust's novel A la recherche du temps perdu (1913--27) is about the stream of consciousness, especially the connection between sense-impressions and memory, but it does not actually use interior monologue. In the second (literary) sense, stream of consciousness is a special style of interior monologue: while an interior monologue always presents a character's thoughts 'directly', without the apparent intervention of a summarizing and selecting narrator, it does not necessarily mingle them with impressions and perceptions, nor does it necessarily violate the norms of grammar, syntax, and logic; but the stream-of-consciousness technique also does one or both of these things. An important device of modernist fiction and its later imitators, the technique was pioneered by Dorothy Richardson in Pilgrimage (1915 -- 35) and by James Joyce in Ulysses (1922), and further developed by Virginia Woolf in Mrs Dalloway (1925) and William Faulkner in The Sound and the Fury (1928). For a fuller account, consult Robert Humphrey, Stream of Consciousness in the Modern Novel (1968).

"stream of consciousness." The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Chris Baldick. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Ocean County College . 15 March 2009

The Life

Machismo: scholars now believe this stems from overcompensation

-- mother occasionally dressed him as a girl as a child. Raised in the

Roosevelt era. Roosevelt had written that a "strenuous life"

represented the American ideal: it was "the only national life [. . .]

really worth leading" (7-8).

Expatriate: Lived in France in the 30s to escape what he saw as the shallow life in America, and also to live cheaply. And when he returned to America with a new baby, our friend William Carlos Williams gave the infant an examination.

Journalist: Like Stephen Crane, who I believe he shares an affinity with, Hemingway first worked as a journalist. This training, according to some critics, is partly responsible for Hemingway's clipped style.

In Green Hills of Africa (1935) he wrote of successful writers: they "increase their standard of living and they are caught. They have to write to keep up their establishments, their wives, and so on, and they write slop" (qtd. in Donaldson 418).

Interesting short essay on his love life that mentions "Snows of Killmanjaro."

The Times

World War I, and its horrors, lies as a backdrop to all of Hemingway's fiction.

For a look at Hemingway's popular competition -- and thus what readers expected in fiction -- see "Dr. Cornthwait's Mistake," a short story published in The American Magazine, 1913 which, like "Indian Camp," also deals with childbirth. I'll bring two pages of this into class so we can compare.

Class Discussion

The Artist: Hemingway often wrote about writers or artists.

The Times

- Corrupting influence of money and society

- "You kept from thinking and it was all marvelous" (1988)

- "The rich were dull and repetitious" (1996)

- War/conflict

- World War I

- Greek border wars -- see above. (1922) Hemingway was war correspondent

His style

- much remarked on and imitated.

- Very clipped, journalistic

- The intro in the text book gives his well known "ice berg" theory of literature: you should leave information unsaid in your work.

- Nostalgic/romantic at times. His Nick Adams stories, roughly autobiographical, trace a boy slowly growing up in rural America , and then experiencing the horrors of war.

- Stoic

- Stream of conscious?

"The Snows of Kilimanjaro"

- The role of the artist

- First titled "The Happy Ending" -- why?

- The critic Linda Wagner-Martin believes that the story contains the following themes: "a person's need to make a good death, the fickleness of fate, the moral guidance a primitive, natural world such as Africa gave cynical Americans. The story also questioned the hold wealth and privilege had upon the American imagination, because even during the Great Depression, value continued to be measured by materialistic standards." Do you see these themes as well?

- Why have Harry die? Symbolism? What does he embody? Does his death represent a larger death?

- Why the flashbacks? What do they add to the story and to Harry's character?

- Why the epigraph? (incidentally, the epigraph didn't appear in the original version of the story published in 1936 Esquire magazine) Connections between epigraph and Harry? Why a leopard?

- What role does Helen play here? Do we view her the same way that Harry views her? Why/why not?

- Why a hyena?

- How does this rely on stream of consciousness?

- What direction is the plane headed towards?

- Why the different endings?

In Our Time

- Why open with "On the Quai at Smyrna"?

- Literally on the quai at Smyrna

- What's the tone of this story?

- How does it present the "time[s]"

- Why italics for the short chapters?

- How is war viewed in these stories (with the exception of "Indian Camp")

- Jacqueline Vaught Brogan believes that the book should be read as a corollary to Cubist art: how could this be true?

Title page from first edition of in our time (1924)

Image from http://www.lib.udel.edu/ud/spec/images/hemingwa/14-2.jpg

"Indian Camp"

- Cycle of life?

- George is bitten -- why? What's his response?

- What is one of the native Americans doing on page 16? Why?

- How is "the Other" presented in this story?

- Why a doctor? Why not some other person going in? Sheriff, for example.

- Why have a child observe this incident? What effect could it have on a child's growth?

- How is Nick's father portrayed in the story?

- How is George portrayed?

- Tone of the story?

- Why have Harry die? Symbolism? What does he embody? Does his death represent a larger death?

- Why the flashbacks? What do they add to the story and to Harry's character?

- The critic Linda Wagner-Martin believes that the story contains the following themes: "a person's need to make a good death, the fickleness of fate, the moral guidance a primitive, natural world such as Africa gave cynical Americans. The story also questioned the hold wealth and privilege had upon the American imagination, because even during the Great Depression, value continued to be measured by materialistic standards." Do you see these themes as well?

- What role does Helen play here? Do we view her the same way that Harry views her? Why/why not?

- Since the title is In Our Times, given these four excerpts, what are the times like? Why, for example, open with "On the Quai at Smyrna."

- Many critics note that the Nick Adams stories amount to primer on Hemingway's views of manhood. With this in mind, what "lessons" about male roles does Nick Adams learn from his time at the Indian Camp?

- Any connections to other writers? Crane? Robinson?

Links

Timeless Hemingway

An interesting, if not scholarly, site on Hemingway -- photos and some info as well.

Ernest Hemingway in his time

Library exhibition on Hemingway

Pictures, Pictures, Pictures

Click to enlarge

|

Georges Braques Image from http://upload.wikimedia.org/ |

Juan Gris Image from |

Quotes from Critics

"Altogether, Hemingway owned six individual titles by Ernest Thompson Seton, published between 1909 and 1921, and a set of collected works published in 1927 as The Library of Pioneering and Woodcraft. The total ranks Seton among Hemingway's favorite writers, a company including Turgenev, Mark Twain, Ezra Pound, and naturalist William Henry Hudson. Hemingway's books by Seton span the range of his writing--children's fiction, animal lore, and practical woodcraft--and together provide important insight into the anti-nationalist and anti-materialist value structure that grounded the Woodcraft organization. Seton's philosophy, placing true civilization in the realm of the primitive, is most succinctly stated in his signed Preface to the 1915 edition of The Woodcraft Manual: "It was Woodcraft that originally constructed man out of brutish material, and Woodcraft may well save him from decay" (v)." (Helstern)

"Because the young father's suicide dwarfs even the horror of the primitive Caesarean, one must acknowledge that among traditional Native Americans the idea of suicide is perhaps more unthinkable than it has ever been in white society. Given the suicide rate among young Indian men today, it is important to emphasize the word traditional. Donald St. John read "Indian Camp" aloud to the Willises, an elderly Ottawa couple who had lived in Michigan during the period when the Boultons lived at the Indian camp near the Hemingway cottage on Walloon Lake . After St. John finished, Mr. Willis commented apologetically, "'Indian no have heart,'" as he "pulled his shoulders together in a little shiver." His wife affirmed, "'They not kill selves for anything. Indian no commit suicide. No believe in suicide. Not like Indian. ... Only white man commit suicide'" (St. John 82-83).

No definitive reason for the Indian husband's suicide can be determined from the facts provided by Hemingway, who allows the motives of this subaltern husband, to use Gayatri Spivak's term, to remain opaque. We know only that he turns his face to the wall at the moment when the doctor pronounces his wife's screams unimportant. In giving up, the young husband, however, embodies a key and almost forgotten stereotype of the American Indian, his "timidity or defeat in the face of White advances and weaponry" (Berkhofer 28-29).

As racial instability manifests itself in the characters of the doctor and the husband, the white Indian and the Indian white, the plot of "Indian Camp" ironically enacts the assimilationist philosophy--"Kill the Indian. Save the child."--of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle , Pennsylvania . Founded in 1879 by Richard Henry Pratt, Carlisle served as the prototype of federal Indian education for nearly four decades. Pratt's voice resounded through discussions of government Indian policy from his first educational experiments with Cheyennes , Arapahos, Kiowas, and Comanches incarcerated at Fort Marion , Florida in the mid-1870s, until his death in March 1924, and beyond ( Adams 37-38). He advocated total immersion in white culture at boarding schools far off the reservation as the only means for inculcating radical lifestyle changes into Indian children." (Helstern)

Helstern, Linda Lizut. "Indians, Woodcraft, and the Construction of White Masculinity: The Boyhood of Nick Adams." The Hemingway Review. 20.1 (Fall 2000): 61-78. Rpt. in Short Story Criticism. Ed. Janet Witalec. Vol. 63. Detroit : Gale, 2004. 61-78. Literature Resource Center . Gale. OCEAN COUNTY COLLEGE . 14 Mar. 2009

"What Hemingway seems to be suggesting in In Our Time is that men's characters are determined, in part, by their responses to human and animal suffering, and (in "Indian Camp") especially women's suffering, a conviction that many feminists share. Such a sensibility to suffering is also, of course, biblical and Judeo-Christian: "[R]ighteousness [in the sight of God] is consistently defined by the prophets, and in the psalms and gospels, as a willingness to care for the most vulnerable people in a culture, characterized in ancient Israel as orphans, widows, resident aliens, and the poor" (Norris, 96). In Hemingway's twentieth-century world, one's responses to the suffering of women (and, perhaps, to the suffering of children, war refugees, and animals, images of which are closely linked in his writings to the suffering of women (2)) similarly reveal one's capacity for humanity." ( Tyler )

Tyler, Lisa. "'Dangerous families' and 'intimate harm' in Hemingway's 'Indian Camp'." Texas Studies in Literature and Language. 48.1 (Spring 2006): p37. Literature Resource Center . Gale. OCEAN COUNTY COLLEGE . 14 Mar. 2009

© David Bordelon 2009