Lesson Plans

Course Links

Lesson Plans

Course Documents Links

Secondary Sources

Quick Links

Library Links

Citing Sources

Allen Ginsberg

Howl, "Footnote to Howl," "In a Supermarket in California"

Terms | Life | Times | Class Discussion | Group Questions | Links | Pictures | Quotes from Critics

Terms to Know

The Beats:

'Beat’ was a term first used by the notorious hustler and drug addict

Herbert Huncke ( 1916 -- 96 ) to describe his own state of anomic

drifting and social alienation. 'Beat’ was quickly picked up by Kerouac

as a triple entendre—an epithet that brought together a sense of being

'beaten’ with the state of being 'beatific’, as well as suggesting the

pulse and 'beat’ of music. The pioneers of the movement were Ginsberg,

whose book Howl ( 1956 ) protested that America had seen 'the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness’, and Kerouac, whose On the Road

( 1957 ) reinvented a mythic landscape of highways, bars, and male

bonding. With other writers such as Gregory Corso ( 1930 -- ) and W.

Burroughs, the Beats developed an aesthetic based on the spontaneity of

jazz, Buddhist mysticism, and the raw urgency of sex.

The group met through their connections with Columbia University. They shared an apartment on 115th Street, New York, where they began to talk of a 'New Vision’—a reaction against what they saw as the sterile nonconformity of post-war America. When this philosophy began to appear as Beat literature, it met with censorship and outrage. Howl was the subject of an obscenity trial in 1956, but was eventually found by the judge to be 'a plea for holy living’. Burroughs's Naked Lunch (1959) was also tried for obscenity by a court in Chicago, and although the prosecution won, the novel was subsequently cleared on appeal.

The

once rebellious Beats are now a respectable area of academic inquiry,

and biographers and Hollywood have confirmed their iconic status.

"Beat and Beat Generation." The Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature.

Ed. Margaret Drabble and Jenny Stringer. Oxford University Press, 2007.

Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Ocean County College

Library. 25 April 2009.

See also longer essay which begins below:

The Beat movement was America's first major Cold War literary movement. Originally a small circle of unpublished friends, it later became one of the most significant sources of contemporary counterculture, and the most successful free speech movement in American literature. It is at once a reclamation of poetry from the modernist pedestal of the New Critics and an attempt to infiltrate the academy itself; as closely associated with the proliferation of Eastern spirituality in America as it is with the drug culture and jazz rhythms of the street.

| "About the Beat Generation" by Jack Kerouac published as "Aftermath: The Philosophy of the Beat Generation"

in Esquire magazine, in March 1958 "The Beat Generation , that was a vision that we had, John Clellon Holmes and I, and Allen Ginsberg in an even wilder way, in the late forties, of a generation of crazy, illuminated hipsters suddenly rising and roaming America, serious, bumming and hitchhiking everywhere, ragged, beatific, beautiful in an ugly graceful new way--a vision gleaned from the way we had heard the word 'beat' spoken on streetcorners on Times Square and in the Village, in other cities in the downtown city night of postwar America--beat, meaning down and out but full of intense conviction--We'd even heard old 1910 Daddy Hipsters of the streets speak the word that way, with a melancholy sneer--It never meant juvenile delinquents, it meant characters of a special spirituality who didn't gang up but were solitary Bartlebies staring out the dead wall window of our civilization--the subterraneans heroes who'd finally turned from the 'freedom' machine of the West and were taking drugs, digging bop, having flashes of insight, experiencing the 'derangement of the senses,' talking strange, being poor and glad, prophesying a new style for American culture, a new style (we thought), a new incantation--The same thing was almost going on in the postwar France of Sartre and Genet and what's more we knew about it--But as to the actual existence of a Beat Generation, chances are it was really just an idea in our minds--We'd stay up 24 hours drinking cup after cup of black coffee, playing record after record of Wardell Gray, Lester Young, Dexter Gordon, Willie Jackson, Lennie Tristano and all the rest, talking madly about that holy new feeling out there in the streets- -We'd write stories about some strange beatific Negro hepcat saint with goatee hitchhiking across Iowa with taped up horn bringing the secret message of blowing to other coasts, other cities, like a veritable Walter the Penniless leading an invisible First Crusade- -We had our mystic heroes and wrote, nay sung novels about them, erected long poems celebrating the new 'angels' of the American underground--In actuality there was only a handful of real hip swinging cats and what there was vanished mightily swiftly during the Korean War when (and after) a sinister new kind of efficiency appeared in America, maybe it was the result of the universalization of Television and nothing else (the Polite Total Police Control of Dragnet 's 'peace' officers) but the beat characters after 1950 vanished into jails and madhouses, or were shamed into silent conformity, the generation itself was shortlived and small in number." From http://archive.tc/kerouac/beat.html |

Man in the Gray Flannel Suit/Organization Man: The latter is the title of an influential book (published in 1956), a classic of American pop sociology by William H. Whyte, which claimed that white-collar employees in large organizations are dominated by corporate life and loyalties. In cutting themselves off from friends, families, and communities, organization men came to assume a new 'bureaucratic, personality structure’. This favoured conformity, a privatized life-style in mass-produced suburbia, and subverted the American values of competitive individualism. The former is a novel based on this same ideal by Sloan Wilson.

"organization man" A Dictionary of Sociology . John Scott and Gordon Marshall. Oxford University Press 2009. Oxford Reference Online . Oxford University Press. Ocean County College. 25 April 2009

Military Industrial Complex:

a country's military establishment and those industries producing arms

or other military materials, regarded as a powerful vested interest.

The term derives from a speech by US President Eisenhower in 1961.

"military-industrial complex." A Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. Edited by Elizabeth Knowles. Oxford University Press, 2006. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Ocean County College Library. 2 May 2009.

Levittown: Neighborhood of prefab houses marketed to urbanites who desired a bit o' the suburbs. A shorthand for the confining and conforming mindset of the 50s.

Surrealism: An anti-rational movement of imaginative liberation in European (mainly French and Spanish) art and literature in the 1920s and 1930s, launched by André Breton in his Manifeste du Surréalisme (1924) after his break from the Dada group in 1922. The term surréaliste had been used by the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire in 1917 to indicate an attempt to reach beyond the limits of the 'real’. Surrealism seeks to break down the boundaries between rationality and irrationality, exploring the resources and revolutionary energies of dreams, hallucinations, and sexual desire. Influenced both by the Symbolists and by Sigmund Freud's theories of the unconscious, the surrealists experimented with automatic writing and with the free association of random images brought together in surprising juxtaposition. Although surrealist painting is better known, a significant tradition of surrealist poetry established itself in France, in the work of Breton, Paul Éluard, Louis Aragon, and Benjamin Péret. Surrealism also attempted to become an international revolutionary movement, associated for a while with the Communist International. Although dissolved as a coherent movement by the end of the 1930s, its tradition has survived in many forms of post-war experimental writing, from the theatre of the absurd to the songs of Bob Dylan . The adjectives surreal and surrealistic are often used in a loose sense to refer to any bizarre imaginative effect. For an introductory account, consult David Hopkins, Dada and Surrealism (2004).

http://www.surrealismcentre.ac.uk Surrealism Centre: Tate Gallery, with Essex and Manchester Universities.

"Surrealism." The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Ed. Chris Baldick. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Ocean County College Library. 3 May 2009.

Bop:

Form of jazz with subtle harmonies and shifting rhythms. It arose in

the late 1940s as a development from the simpler swing style. Complex

and dynamic, involving the extensive use of improvisation, the movement

was pioneered by musicians such as Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie.

"be-bop." World Encyclopedia. Philip's, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Ocean County College Library. 3 May 2009.

Cold War: The "war" between the Soviet Union and the United States, which ran from 1945 (or so) to the end of the 80s. The "war" is cold and in quotation marks because it did not involve direct military action between the two countries. Instead, the "war" was fought by 1) an arms race (he who ends up with the most nukes wins) and 2) by proxy: i.e. in/through other countries with the Soviets or Americans supporting one or the other side -- cf. Vietnam, the Middle East, and South America.

The Life

See textbook for his very interesting life. Thirty years old when Howl

was first published. A close knit group of writers/thinkers/dreamers

consisting of Ginsberg, Jack Keuroac, Neal Cassady, William Burroughs,

provided an early audience and support. The formed the nucleus of the

Beats.

His mother's institutionalization in mental hospitals and schizophrenia also obsessed Ginsberg, an obsession illustrated by images of insanity in his poetry.

Ginsberg worked in an ad agency.

The Paris Review interview has some interesting comments on Howl.

For an "on the ground" feeling, check out New York Times report on the San Francisco "scene" which mentions Ginsberg.

West Coast Rhythms; West Coast Rhythms

By RICHARD EBERHART. New York Times (1857-Current file). Sep 2, 1956. p. BR4 (2 pages)

For fascinating documentary of Ginsberg and his times, watch the 1994 film The Life and Times of Allen Ginsberg.

The Times

Conformity was all the rage. And conformity equaled a Victorian view towards sex: witness the twin beds for Ricky and Lucy in I Love Lucy, and the waist up only footage of Elvis Presley on The Ed Sullivan Show (those gyrating hips were just too suggestive). Imagine how the explicit sexual imagery in Howl was received: breath of fresh air or Satan's seed.

For an overview essay on the 50s, see the Epilogue: Final Thoughts on the Decade.

And consider the following 1950s interviews from from David Reisman's "The Search for Challenge:"

A study "at the University of Michigan for the Michigan Bell Telephone Company in which a group of articulate adults were invited to let their imaginations roam free and to tell trained interviewers what sort of things they would like to see in the 'world of tomorrow.' Out of 126 interviews, mainly with well-educated respondents, there were, in fact, few suggestions that were at all visionary. Respondents want a machine which will bring them the morning newspaper from the doorstep [it's called the internet]. They want conveyor-belt highways and drive-in supermarkets and automatic car controls. They want a personal air-conditioning unit inside their clothes. [. . . .] Or they want a machine [359] which will bring them any sight, sound, smell, or climate they choose without having to go out to find it. They want to be able to bring back fond memories at will and to erase annoyances at will. One wants a device to look a doctor over without going to his office, another a device to make it easy to complain to a supercilious salesperson, or a gadget to allow one safely and anonymously to bawl out somebody. One wistfully asks, and here is one of the few quasi-political suggestions, for some means of making suggestions to the legislative government (that's his term), and still another says, 'I want to be able to visit relatives and friends without missing church.' One wants 'more variety in my daily living -- a surprise every day.'" (Reisman 358-359

From David Reisman's "The Search for Challenge" in Abundance for What? 1958

For an idea of the consumer culture, see these TV Commercials from 1950

And for an idea of the geopolitical, read Henry Luce's seminal essay "The American Century," which, depending on your outlook, heralded our greatness or was the nail in the coffin. Either way, it was read, embraced, and perpetuated in our foreign policy. It's part of the "atomic jukebox" that Ginsberg refers to in "Howl."

A Trio of Radio Stories

After 50 Years, Ginsberg's ' Howl ' Still Resonates

October 27, 2006 ... After 50 Years, Ginsberg's ' Howl ' Still Resonates. by John McChesney. ... Related NPR Stories. Revisiting Ginsberg's First Reading of ' Howl ' May 20, 2006. ... By John McChesney http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=6393328

Revisiting Allen Ginsberg's ' Howl ' at 50

May 20, 2006 ... Revisiting Allen Ginsberg's ' Howl ' at 50. ... Lawrence Ferlinghetti was at the Six Gallery to hear the 29-year-old Allen Ginsberg read " Howl " for the first time. ... By Tom Vitale http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5419033

Birth of the Beat Generation: 50 Years of ' Howl '

October 07, 2005 ... SIEGEL: Did " Howl " spawn lots of imitative little " Howls " that came after it? I mean, do you start seeing a genre of Ginsberg -like poems right after that? ... By Robert Siegel http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4950578

And now for something completely different: a story on drugs and transcendentalism from Radiolab

Can one blissful moment change your life? Producer Andy Mills introduces us to Reverend Mike Young,

a man who can pinpoint a pivotal handful of minutes in the 1960s that

he claims did just that. As a college student, he was part of a study in

which theology students were given psilocybin (a.k.a. magic mushrooms)

in a church basement during a Good Friday service. This might seem

ridiculous, and in fact, it wasn't long after that the use of these

kinds of drugs for both science and recreation was banned. Nonetheless,

we follow our curiosity to some current psilocybin experiments that

demonstrate the powerful and surprising effects of psychedelic drugs. Dr. Roland Griffiths and Charlie Bessant

help us pin down these hard-to-describe, intense feelings of rapture.

And Andy finds himself reassured about a deeply personal experience from

his own past.

Class Discussion

Began writing the poem in 1955 (Ower). First performed in 1956 in San Francisco.

- Remember that humor is an important part of this work.

- The 50s - conformity, nuclear bombs, jazz

- Influences - Kerouac, Whitman, Celine, Genet, Blake, Cezanne drugs, spiritualism (particularly eastern religious philosophies), Bible, jazz.

- And like Whitman (and other writers), sex as a productive force, metaphorically giving birth to new sensations, ideas, and even cosmos.

- Sent early draft to William Carlos Williams: why him and not, say, T. S. Eliot? Williams wrote introduction to original edition.

- On the style of the poem, consider the following explanation by Ginsberg: "The lines are the result of long thought and experiment as to what unit constitutes one speech-breath-thought . . . " (153). "I have leaned more toward capturing the inside-mind-thought rather than verbalized speech. This distinction I make because most poets see the problem via Wordsworth as getting nearer to actual speech, verbal speech" (153)

- Given the above, the poem moves by association, one thought leading to the next in a seemingly organic fashion.

- Why "Howl"? Why not "Shout" or "Scream"?

- In the first line, the word "hysterical" was originally "mystical": how does the change effect the poem?

- What poetry we've read earlier does Ginsberg's work evoke?

- How do the long lines affect your reading/understanding of the work?

- Why the drug imagery? How do drugs fit into the poem?

- What does it mean to purgatory your body? Why not torture? (line 10)

- How do the lines 17 and 18 hold together?

- Line 32: how do the "wail"s differ?

- Spirituality?

- What is "Golgotha"?

- Who/what does Moloch represent? Why a god that entails burning children? (line 79)

- When Ginsberg wrote the first draft, he didn't think it would be published (Paris Review 8). How does this effect your understanding of the work?

- Paris Review 10 "what happens if you make a distinction between what you tell your friends and what you tell your Muse? The problem is to break down that distinction: When you approach the Muse to talk as frankly as you would talk with yourself or with your friends." How does this breaking down of distinctions work its way through the poem?

- Spell out the meanings/associations (note plural) of the phrase "hydrogen jukebox"?

- Consider the use of repetitive phrasing throughout the poem. What's its purpose?

- Many interpret this as a poem of protest (which Ginsberg acknowledges, but suggests it's not the sole focus of the poem). As a poem of protest, what is it protesting?

- Connect Kerouac's "About the Beat Generation" above to Howl.

- How is this poem like Eliot's Wasteland? How is it different?

- Spell out the meanings/associations (note plural) of the phrase "hydrogen jukebox" (line 15)?

- Geoffry Thurly notes that "In `Howl,' Ginsberg's ability to move easily from exultation and pain to humour and self-mockery is radically important: the total impact of the work is composed of many different sorts of effect. The responses called for range from pity to terror, through laughter, disgust and contempt:" Trace out these emotions -- pity, terror, laughter, disgust, contempt -- and discuss why/how this makes the work "important"?

- How does the "Footnote to Howl" work in relation to "Howl" itself?

- In a 1966 Paris Review interview, Ginsberg discussed his word choice in "Howl," rhetorically asking "what happens if you make a distinction between what you tell your friends and what you tell your Muse? The problem is to break down that distinction: When you approach the Muse to talk as frankly as you would talk with yourself or with your friends" (10). How does this breaking down of distinctions manifest itself in the poem?

- Gregory Stephenson traces the shape of Howl and "Footnote" as moving

from protest, pain, outrage, attack, and lamentation to acceptance, affirmation, love and vision--from alienation to communion. The poet descends into an underworld of darkness, suffering, and isolation and then ascends into spiritual knowledge, blessedness, achieved vision, and a sense of union with the human community and with God. The poem is unified with and the movement carried forward by recurring images of falling and rising, destruction and regeneration, starvation and nourishment, sleeping and waking, darkness and illumination, blindness and sight, death and resurrection." (Stephenson)

Trace out these steps in the poem.

- Does the poem still retain the capacity to shock? Is it still necessary to read/write such a poem today?

Fantastic movie on Ginsberg's life and times. You may have to allow active X on your browser to access it.

Reading at the Poetry Center, San Francisco State University

October 25, 1956

complete recording (24:41): ![]() MP3

MP3

![]() A Supermarket in California (2:21)

A Supermarket in California (2:21)

After 50 Years, Ginsberg's 'Howl' Still Resonates

by John McChesney

Wiki page on Howl was good on 4/24. Particularly good were the notes.

Ginsberg page at Poets.org

Interview with Kerouac on the Steve Allen show

Great poem by Ginsberg -- America

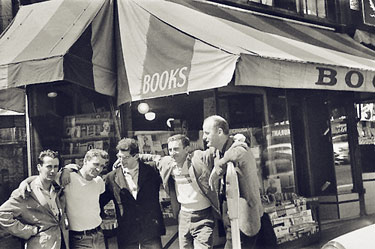

Pictures, Pictures, Pictures

Click to enlarge

|

Ginsberg and friends at City Lights

|

Front cover of original edition, published by City Lights Bookstore |

Illustration by Lynd Ward (1980) from Allen Ginsberg, Howl, ed. by Barry Miles |

Nighthawks (1942)

Archetypal Edward Hopper image that captures the alienation felt by many through the 50s

Paul Cezanne

The Cardplayers

(1892).

Ginsberg makes much of following Cezanne's theory of art as forms instead of realistic images.

Quotes from Critics

"Ginsberg's greater religious commitment ![]() `Howl' is about people who have committed themselves irrevocably to a life of perhaps excessive spiritual intensity" (Thurley)

`Howl' is about people who have committed themselves irrevocably to a life of perhaps excessive spiritual intensity" (Thurley)

"In `Howl,' Ginsberg's ability to move easily from exultation and pain to humour and self-mockery is radically important: the total impact of the work is composed of many different sorts of effect. The responses called for range from pity to terror, through laughter, disgust and contempt:" (Thurley)

The great virtue of `Howl'

is the warmth and sympathy with which it celebrates what the poet

understands is both sublime and absurd. This is especially true of the

third section of the poem: Carl Solomon went through the whole silly

serious routine with Allen Ginsberg. Yet he did go mad, and what are

the alternatives in modern society? ![]() (Thurley)

(Thurley)

Critic: Geoffrey Thurley

Source: The American Moment: American Poetry in the Mid-Century, 1977. Reprint by St. Martin 's Press, 1978, pp. 172-86. Reproduced by permission

Critic: Gregory Stephenson

Source: The Daybreak Boys: Essays on the Literature of the Beat Generation, Southern Illinois University Press, 1990, pp. 50-58. Reproduced by permission

" "Howl" expresses a contemporary confrontation with the concept of transcendence and examines the personal and social consequences of trying to achieve and return from the state of transcendence." (Stephenson)

"Transcendence and its attendant problems may be summarized in this way: the poet, for a visionary instant, transcends the realm of the actual into the realm of the ideal, and then, unable to sustain the vision, returns to the realm of the actual. Afterwards the poet feels exiled from the eternal, the numinous, the superconscious. The material world, the realm of the actual, seems empty and desolate. (Poe, in The Fall of the House of Usher, describes this sensation as "the bitter lapse into everyday life, the hideous dropping off of the veil.") The poet (like Keats' knight at arms) starves for heavenly manna. This theme of transcendence is treated in the work of Coleridge, Wordsworth, Keats, Shelley, Nerval, Rimbaud, and many other poets and writers. "Howl" describes and resolves the problems, using as a unifying image the archetype of the night-sea journey." (Stephenson)

"The movement of "Howl" (including "Footnote to Howl") is from protest, pain, outrage, attack, and lamentation to acceptance, affirmation, love and vision--from alienation to communion. The poet descends into an underworld of darkness, suffering, and isolation and then ascends into spiritual knowledge, blessedness, achieved vision, and a sense of union with the human community and with God. The poem is unified with and the movement carried forward by recurring images of falling and rising, destruction and regeneration, starvation and nourishment, sleeping and waking, darkness and illumination, blindness and sight, death and resurrection." (Stephenson)

"Ginsberg has phrased the issue in the first section of the poem as "the difficulties that nuts and poets and visionaries and seekers have. . . . The social disgrace-- dis grace--attached to certain states of soul. The confrontation with a society . . . which is going in a different direction . . . knowing how to feel human and holy and not like a madman in a world which is rigid and materialistic and all caught up in the immediate necessities. . . ." The anguish of the visionary in exile from ultimate reality and desperately seeking reunion with it is intensified by a society which refuses to recognize the validity of the visionary experience and maintains a monopoly on reality, imposing and enforcing a single, materialist-rationalist view." (Stephenson)

"Ginsberg was not alone in lamenting the destruction of a generation of frenzied, Dostoyevskian questers. In an early article on the Beats, Jack Kerouac mourned "characters of a special spirituality . . . solitary Bartlebies staring out the dead wall window of our civilization. The subterranean heroes who'd finally turned from the 'freedom' machine of the West and were taking drugs, digging bop, having flashes of insight, experiencing the 'derangement of the senses,' talking strange, being poor and glad, prophesying a new style for American culture . . . [but who] . . . after 1950 vanished into jails and madhouses or were shamed into silent conformity." Ken Kesey, in his novel One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest, also treats the issue of the imposition of a false, shallow, materialist-rationalist reality on the human spirit and the consequent persecution and oppression of those who cannot or will not accept the official reality." (Stephenson)

"Ginsberg presents a comprehensive nightmare image of contemporary society, an inventory of terrors and afflictions that is as penetrating as Blake's " London ." And like Blake in " London ," Ginsberg places the source of human woe within human consciousness and perception. Moloch is a condition of the mind, a state of the soul: "Mental Moloch!"; "Moloch whose name is the Mind!" We are born, according to Ginsberg, in a state of "natural ecstasy," but Moloch enters the soul early. (See Blake's "Infant Sorrow.") We can regain that celestial, ecstatic vision of life ("Heaven which exists and is everywhere about us!") by emerging from the belly of Moloch, the monster that has devoured us, who "ate up . . . [our] brains and imagination." We can "wake up in Moloch!"" (Stephenson)

"The acceptance of the body is essential for Ginsberg, for the senses can be a way to illumination. The body is where we must begin. Throughout Howl sexual repression or disgust with the body or denial of the senses have been seen as forms of Mental Moloch: "Moloch in whom I am a consciousness without a body!"; "where the faculties of the skull no longer admit the worms of the senses." That is why the " Footnote " proclaims: "The soul is holy! The skin is holy! The nose is holy! The tongue and cock and hand and asshole holy!" Body and spirit are affirmed and reconciled." (Stephenson) CONNECTION TO WHITMAN.

"Ginsberg's sense of our common human necessity to redeem light from darkness, to seek vision and to practice virtue, is communicated in verse by the breath-measured, long-line, chant rhythm of "Howl." Andrew Welch observes that:

The chant rhythm is a basic use of language that both reflects and directs social action toward community goals, a force that seems never to be far away when this rhythm enters poetry. In the Eskimo dance song, in the Navaho and Australian chants, in the prophecies of the Ghost Dance and of the Maya poet Chilam Balam, and in the poems of Ginsberg and Baraka, there is rhythmically and thematically a strong sense of movement and action, a communal rhythm enforcing communal participation and communal identity.

In this way, "Howl" is linked not only to the romantic tradition but also to the preliterary, oral, magic incantations of the universal shamanist tradition." (Stephenson)

Howl and Other Poems marked Ginsberg's emergence to artistic maturity and established him as a leading voice of the Beats. The famous title poem recalls the spiritual movement of T.S. Eliot 's The Waste Land and Ezra Pound 's hell cantos, Cantos XIV and XV. Thus, "Howl" begins with a personal crisis engendered in its creator by a sick society but concludes with his renewal through a vision transcending contemporary evils. This process may be described as a "cycle" of death and rebirth, or (as William Carlos Williams suggests in his introduction to "Howl") as a Dantesque journey through hell. Three distinct yet interrelated stages of such an imaginative descent and return are marked by the three sections of "Howl" proper, to which is appended a concluding "Footnote."

Part 1 attempts to convey the spiritual essence of the Beat movement through a biographical collage that includes allusions to the lives of Kerouac, Burroughs, Huncke, Cassady, Solomon, and Ginsberg himself. The poet's portrayal of "the best minds of ... [his] generation" is characterized by an ambivalence summed up in the double meaning of Beat, which signifies both the derelict and the beatific. To put the matter in terms of one of Ginsberg's favorite poetic genres, the first section of "Howl" is an elegy, turning upon the two opposing poles of lament and celebration. On the positive side, Ginsberg affirms with a mixture of prophetic seriousness and "comic sympathy" the Beat practice of Blake's aphorism that "The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom." By radical "derangements" of their life-styles and consciousnesses, Ginsberg's friends have attempted to break out of the twofold spiritual prison of a material universe and a materialistic America . Nonetheless, while the Beats have to some degree succeeded in making the "ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo," they have also paid a terrible price in poverty, affliction, and even personal destruction. In part, they have suffered directly from their unsympathetic and at times repressive society, as has Carl Solomon in a further period of incarceration in Rockland Mental Hospital . However, Ginsberg's friends have also been victimized more subtly. Thus, their belief that a desperate situation necessitates extreme measures has led to forms of rebellion that sometimes recoil tragically upon their practitioners. The drug addiction, alcoholism, and other forms of personal dereliction among the Beats, while from their viewpoint necessary measures of revolt and spiritual affirmation, have still left them "starving hysterical naked."

Part 2 of "Howl" evokes mythically the evil in contemporary America that has victimized the Beats. Such a demonic power is represented by the Canaanite god Moloch, "within whose brazen image living children were ... burned as sacrifices." Ginsberg's symbolism here was, according to Jane Kramer , inspired by "a peyote vision that ... the poet had in San Francisco, staring ... at the ... Sir Francis Drake Hotel and being reminded of Moloch by the tower's grinning, mask-like facade." The sinister divinity of Ginsberg's vision becomes in part 2 of "Howl" primarily a Blakean mythic image for a fallen state of mind. This is compounded of loveless indifference, judgmental puritanism, worldly pride, and brute materialism. The spiritual perversions represented by Moloch in turn produce what Ginsberg sees as the infernal nightmare of American society during the 1950s. In this regard, Moloch is externalized as an economic machine creating spiritual poverty and physical deprivation in the midst of a gross affluence. America 's sickness of soul is likewise manifested in its "stunned" government whose militarism is leading inevitably to "a cloud of sexless hydrogen." Finally, the Moloch mentality is for Ginsberg expressed with particular horror in New York City , which, rather than San Francisco , is suggested by the "skyscrapers ... [that] stand in the long streets like endless Jehovahs." The buildings of Manhattan are in Ginsberg's view monstrous symbols of a national psychic derangement. Each with a "thousand blind windows," and ranked like "granite cocks," these edifices show how a purblind materialism perverts the vital energies and produces a terrible hardness of heart.

Ginsberg stresses in part 2 of "Howl" that Moloch has exacted a heavy toll from his worshippers and from rebels alike. The latter are not simply victimized by the false god but are to some extent themselves infected with his attitudes. Ginsberg confesses that Moloch has entered his own mind early, making him a "consciousness without a body" and frightening him from his "natural ecstasy." Yet his recognition that America 's sickness is also within is paradoxically the basis of a major moral victory. Thus, there is intimated in part 2 a dialectical reaction stemming from the poet's full awareness of the influence of Moloch upon his psyche. This painful revelation at once enables and stimulates Ginsberg to banish Moloch's shadow from his mind, and so to be spiritually reborn. In particular, the poet apparently ceases his destructive self-rejection as "Crazy" and as a homosexual. He thereby overcomes the division within himself that caused much of his despondency and liberates his affirmative spiritual energies.

The poet's inner renewal is indeed not apparent in part 2 of "Howl" itself, which concludes with an anguished despair at the seeming collapse of the regenerative religious impulse represented by the Beats. Nonetheless, in part 3, Ginsberg is able through his personal rebirth to find victory in the apparent defeat of his associates. Thus, the incarceration of Carl Solomon in Rockland Mental Hospital inspires the poet to a triumphant affirmation of spiritual solidarity and love. Having accepted himself, Ginsberg is able more fully to empathize with his friend, who has suffered in much the same manner as the poet. Ginsberg's new bond with Solomon in Rockland likewise constitutes an indirect reconciliation with the poet's insane mother, whom he sees in "Kaddish" as another victim of a hostile political and social environment. Although Ginsberg's victory over Moloch may seem purely personal and therefore modest, it is ultimately far-reaching in its implications. The fuller meaning of the poet's own triumph is shown by that of Solomon, who has in the madhouse become the prophet-Christ of a Blakean "Mental Fight" against Moloch. Solomon has attained in his very travail a vision that has liberated his own soul from the evils of his society, and that will help to redeem America both spiritually and socially.

The essential basis of such a prophetic awareness is specified in the "Footnote" to "Howl." This is the belief that everything is charged with divinity and is therefore sacred. Of particular importance here is Ginsberg's assertion that "The tongue and cock and ... asshole [are] holy," a conviction that of course opposes Moloch's puritanical denial of the body and its instincts. Once the whole self is accepted as an expression of godhead, even its apparent degradation and dereliction may be affirmed. It is then possible to accord the same recognition to all beings, however sordid or evil they may appear. Thus, Ginsberg's universal paean in the "Footnote" includes even the American civilization and the material cosmos which before seemed so threatening. The former is represented by the locomotive and the latter by "the clocks in space," both images of demonic mechanism which are now redeemed in a higher vision.

"Howl" clearly illustrates the boldly innovative and even radical approach to metrics that (as Paul Portugés has demonstrated) is generally characteristic of Ginsberg's mature verse. In this regard, "Howl" was influenced by the prosodic practice of William Carlos Williams , Christopher Smart , Blake, Whitman, Guillaume Apollinaire, and García Lorca. More theoretically, the versecraft of "Howl" arises in part from the Romantic notion that artistic form is, in Blake's words, "the bound or outward circumference of Energy." Thus, the free rhythms of "Howl" and its widely varying lengths of line and poetic phrase represent Ginsberg's attempt to remain faithful to the fluctuations that characterize the "natural flow of the mind" in a state of intense imaginative excitation. Another significant factor in the prosody of "Howl" is its author's consideration of his breathing capacity when his poem is read aloud. Coordinating the physical and psychic factors just mentioned, Ginsberg in "Howl" employs units of "one speech-breath-thought" as a metrical base. Such divisions in turn often subtly interplay with the onward sweep of a long line. Ginsberg's complex and flexible versecraft, by permitting a wide variety of verbal effects, is of course in keeping with the tradition of oral incantation to which "Howl" so obviously belongs.

John Ower, University of South Carolina

Source: Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 5: American Poets Since World War II, First Series. A Bruccoli Clark Layman Book. Edited by Donald J. Greiner, University of South Carolina . The Gale Group, 1980. pp. 269-286

![]()

Ginsberg from 1956 Letter to Richard Eberhart (writer of New York Times essay on San Francisco poets)

"Howl is an 'affirmation' of individual experience of God, sex, drugs, absurdity etc. Part I deals sympathetically with individual cases. Part II describes and rejects the Moloch of society which confounds and suppresses individual experience and forces the individual to consider himself mad if he does not reject is own deepest sense. Part III is an expression of sympathy and identification with C. S. who is in the madhouse -- saying that his madness basically is rebellion against Moloch and I am with him, and extending my hand in union. This is an affirmative act of mercy and compassion, which are the basic emotions of the poem. The criticism of society is that 'Society' is merciless. The alternative is private, individual acts of mercy. The poem is one such. It is therefore clearly and consciously built on liberation of basic human virtues"

To call it [a] work of nihilistic rebellion would be to mistake it completely. Its force comes from positive 'religious' belief and experience. It offers no 'constructive' program in sociological terms -- no poem could. It does offer a constructive human value -- basically the experience -- of the enlightenment of mystical experience -- without which no society can long exist" (154)

© David Bordelon 2009