Introduction

Introduction

Notes From the Underground

(1864)

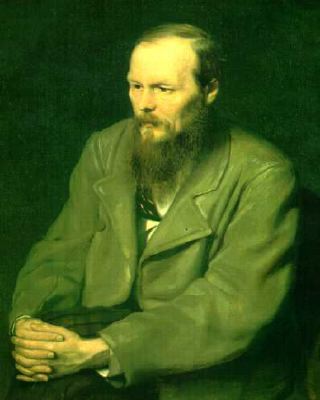

Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821-1881)

This page is the work of a Susan Ambrosino, Michael Howell, Stephen Howard Debrecki, Rocco Nicoletta

Biographical Cultural/Historical Philosophy Psychological Questions to Consider

Introduction

Introduction

Biographical

Steven Howard Debrecki

Dostoevsky Meet Dostoyevsky

Also known as Feodor Mikailovich Dostoevski, sometimes spelled Fyodor Dostoyevsky sometimes spelled Dostoevsky. Dostoevsky’s extraordinary literary life ended on January 28,1881 (Barzun 1369). He died at the age of 60. Oddly enough that is also where the story begins. In the hundred and twenty years since his death it has been said by such distinguished individuals as Albert Einstein that he believed he had obtained more from Dostoevsky than from one of the greatest physicists of all time that being Carl Friedrich Gauss (1349). Fredrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (1844–1900) is another of the remarkable individuals who acknowledged his debt to Dostoevsky’s psychology (Barzun 1349). It would appear, when considering what is Beyond good and evil, that Dostoevsky was there first. Other notables, such as French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus have also acknowledged their debt to Dostoevsky (Barzun 1350).

Dostoevsky is one of the most widely read novelists of the nineteenth-century (Barzun 1349). A writer for the ages and one who possess the true spirit of universal appeal. Dostoevsky cults have sprung up all over the world. They have been born, died and been reborn again. Whether questioning the "sick consciousness" as in Crime and Punishment or the "acute consciousness" such as the one in Notes From in the Underground it is the internal struggle of the psyche that is ever present in Dostoevsky’s work as if to say Dostoevsky meet Dostoyevsky.

Feodor Dostoevsky was the son of an army surgeon who was murdered by his serfs. The drunken serfs, on the humble country property the family owned, poured vodka down the father’s throat until he gagged to death (Surviving Desire). The Dostoevsky’s belonged to the proletarian middle-class (Barzun 1350). Dostoevsky left the farm for Saint Petersburg when he was seventeen. He spent five years there in Military Engineering School. His reading was prolific. Pushkin, Gogol, and foreign writers such as Shakespeare, Byron, and Homer were also included on his literary menu (Barzun 1350). Dostoevsky seems to have enjoyed the nightlife during these years (Barzun 1351). This may have been the genesis of his future lifelong gambling addiction.

In 1849 at the age of 28, Dostoevsky’s early experiments with a hand press and political reform earned him and twenty-one of his comrades, known as the Petrashevsky Circle, a death sentence (Barzun 1354). They were condemned to be shot in Semyonev Square. Only shortly before the execution was to be carried out the czar commuted the sentence to four years at hard labor in a prison at Omsk, Siberia to be followed up by four years as a soldier. He was also banished from Saint Petersburg for a period of ten years.

Dostoevsky came to believe that he had committed a crime and that the punishment he received fit the crime that he had committed. "Dostoevsky entered prison a young radical and unbeliever, and he left it with a heightened respect for the authority of the crown and a new faith in the teachings of Christ" (Barzun 1355). Thus begins the saga in his writings which salvation by suffering is the only means of redemption (Barzun 1355). Hard labor, stench and chains among every manner of murderer and thief was now his teacher. It is here, in Omsk, that he has his first epileptic seizure (Barzun 1354). Through the New Testament (the only book he was allowed to read) and his other experiences at Omsk he rediscovers Jesus Christ.

Dostoevsky if freed on January 23, 1854 (Barzun 1355). At the age of 33 he now moves on to Semipalatinsk, a Siberian garrison town to finish his sentence as a soldier. The only significant event at this point seems to be his reading and love for Marya Isaeva. She however, ends up with a schoolteacher for some time. It is here that the theme of the triangular love affair begins. He marries Marya in 1857. Dostoevsky is now 36 and in financial direr straits again (Barzun 1355). Despite this the writing continues.

As an ex-con Dostoevsky seeks and receives permission to publish some of his work. After a great of deal of pleading and the aid of a highly placed official, he was permitted to resign from the army (Barzun 1356).

Dostoevsky publishes The House of the Dead a work in which he relates his experience at Omsk. It is a deep psychological study of the more striking convicts he met in Omsk.

In 1863, he leaves his sick wife and his magazine (Time) in his brother’s care. He takes off on an European tour for ten weeks with reckless abandon. He returns briefly to find the government has suppressed his magazine Time (1358). After a short stay Dostoevsky returns to Europe, broke and now in love with Polina Suslova. Luck and love leave him stranded at the roulette wheel.

In 1864 he changes the name of his magazine to Epoch because Time was shut down by the government. This is also the year Notes From the Underground appears. Late in 1864 and early 1865 Dostoevsky looses his wife, brother and the Magazine the Epoch (Barzun 1358).

In 1867 Dostoevsky marries Anna Snitkina, his stenographer, twenty-five years his junior. To escape prosecution from creditors they travel to Europe and live in constant poverty due to Dostoevsky’s gambling. But he continues to write to Anna and Anna stays devoted to him through all of his human manifestations (1361).

In 1874 his wife takes over the publication of his work and their financial condition improves. Dostoevsky continues to write and publish (1366). Right up to and including his last masterpiece The Brothers Karamazov.

On January 28, 1881 Feodor Mikailovich Dostoevski, sometimes spelled Fyodor Dostoyevsky sometimes spelled Dostoevsky dies and leaves behind him one of the greatest collections of literature on the dualistic nature of man’s consciousness that the literati, pundits, wags, scholars and academics have ever seen.

Works Cited

Simmons, Ernest, T. European Writers: The Romantic Century: Volume 7. Eds. Jacques Barzun and George Stade, New York:

Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1985. 1349-1370.

Kashdan, G. Joanne, Masterplots Complete 2000. CD-ROM. California: Salem Press, 2000.

Surviving Desire. Dir. Hal Hartley. Perf. Martin Donovan, Matt Malloy, Rebecca Nelson, Julie Suklman, and Mary Ward. Fox Lober

Films, 1991.

Further Reading

There is a great deal of translations available by various translators and various publishing houses. Somewhere between amazon.com and the Ocean County Library you will find a happy medium. All suggested readings are by the author himself.

Notes From the Underground

Crime and Punishment

The House of the Dead

The Idiot

The Gambler

The Brothers Karamazov

Cultural/Historical

Michael Howell

When Dostoevsky was allowed to return from exile to Russia in early 1859, he was still not allowed to return to his home in Petersburg. He chose to live in Tver ( Kalin of today), which is Northwest of Moscow on the Volga River. Tver is known as an industrial center, and an important communications point.

In 1859 the Russian government lifted the restriction and allowed him to return to Petersburg. The Petersburg he returned to was a city of about 500,000 inhabitants. Unlike Tver, Petersburg was noted for its marketing and administrative sections rather than industry.

As was the case in all of Russia, the Russian Orthodox Church was under government control being run by lay officials, and looking more " like a secular government department" (Watson 241). Little attention was paid to theological doctrine.

The major problem facing Tsar Alexander 11, the Emperor of Russia, was the emancipation of the serfs. In 1859, there were approximately 19 million state peasants in Russia, along with 22 million serfs. The most important questions to be answered before the emancipation could take place were, " first, how much land was to be given to the peasants and on what terms, secondly, what kind of administrative authority was to take the place of the self –owning landlord" (Watson 341).

In 1861, serfdom was abolished, along with corporal punishment, but civil unrest erupted. Dissatisfaction sprang from the universities. "There were disturbances in nearly all the universities, so serious they had to be closed,"(Stephenson 113) disorders in Petersburg and Moscow gave signs of revolutionary activity.

Dostoevsky visited London in July of 1862 and " the thing that struck him most was the contrast between the "colossal fašade" of riches, luxury and general prosperity of the few and the abject poverty of the many and their "coolie-like" acquiescence in their fate"(Magarshack XV).

During his visit to England the conditions he found appalled him; children working in textile mills 12 hours per day, with mill owners adopting orphans so that they would have cheap labor readily available. Approximately one-half of the children in England and Wales, 5 million were working in deplorable conditions and not attending school. Workhouses existed for the many unemployed adult and children, and for those who needed public assistance, the workhouses were managed by the government and purposely kept a below minimum living standards to encourage the needy not to stay.

There was also a large income disparity between the classes, for example the average earnings of the wealthy class was 30,000 pounds per year, while the lower class which included shop assistants and domestics earned 12 to 20 pounds per year, a difference of 2,500 %. Three-fourths of the work force performed manual labor, either in agriculture or factories, with domestic service the largest employer for women. The average worker "earned just enough to stay alive", (Mitchell 18) and the children of most families had to work to contribute to the support of the household.

The London that Dostoevsky visited in 1862 had over 500,000 homes, and street surfaces constructed of granite which changed to fine powder as horse drawn carts were pulled over them. This "mixed with two to ten cart-loads of horse droppings per mile of street per diem, besides an unknown quantity of sooty deposits discharged from a half a million smoking chimneys"(Mitchell 116), may have been the reason that tuberculosis was London's leading killer.

Tuberculosis was not the only disease that was of concern in London, epidemics of influenza, scarlet fever, cholera, typhus and typhoid were prevalent during this time. Queen Victoria's husband , Prince Albert, had recently died as the result of the typhoid epidemic.

In 1862 leisure and pleasure activities while not accessible to all, began to become available to the English middle and upper class. Vacations to local coastal towns, Deal, Hastings and Ramsgate, were in vogue, the mother and children staying for the summer, with father appearing on weekends.

Horseback riding had become a means of pleasure and fox hunting became a "social ritual",(Magarshack 228) for the aristocracy. Only the wealthy partook in hunting as it required "weekday leisure in the winter and enough money to keep good horses" (Magarshack 216).

Dostoevsky's observation of what was happening in his own country, and his visit to England where he encountered the abject poverty of the working class, I believe greatly influenced his writing in Notes from the Underground.

Works Cited

Watson, Seton, Hugh. The Russian Empire: 1801-1917. Oxford, England: New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Stephenson, Graham. Russia from 1812 to 1945: a history. New York: Praeger, 1970.

Mitchell, Sally. Daily life in Victorian England. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1996.

Dostoyevsky, Fyodor. The Best Short Stories of Dostoyevsky. Trans. Margarshack David New York: Random house, 1996.

The word philosophy comes from a Greek, or Hellenistic, origin. It quite literally means love of wisdom. It was first used circa 600 BC by Pythagoras, when the tyrant Philius asked him who he was and he replied, "I am a philosopher" (Miller 3). He probably thought that his little joke would not be remembered more that but a few minutes, but on the contrary it would soon turn into a school of thought and a way of life that would span the globe in every direction. One place in particular that was affected by this "love of wisdom" is the frozen, permafrost laden northeast country of Russia where Fyodor Dostoievsky was born.

Russian philosophy, during most of the nineteenth century, came from outside of the academy. The philosophers of Russia during this period of time paid little attention to the more technical disciplines such as logic, epistemology (the study of knowledge), philosophy of language or the philosophy of science. Moreover, they paid more attention to philosophical anthropology - that which concerns human nature; and ethics, along with political, historical, and religious philosophy (Audi 580, 703).

This type of thought gave way to a movement that took place during the 1840’s called Romanticism. The romantics stood for freedom of form and loved open horizons and endless perspectives (Cizevskij 3). To romantics, reality was what they saw in the world and in their own souls in accordance with their view of the world (Cizevskij 4). The optimism of the 1940’s lead to another, darker movement that took place during the 1860’s. This one was quite different from Romanticism, it was called Nihilism. Nihilism was basically a rejection of values as having any objective validity and anything transcendent. To the nihilist life was ultimately meaningless (Miller 385,586). Dostoievsky used these two different types of views to build a character, the underground man of Notes From the Underground. The first section shows the underground man in the ideological rip of the nihilism of the sixties; the second as a perfect product of the romanticism of the forties. (Frank 38)

Soren Kierkegard wrote, in one of his writings- Fear and Trembling, "If philosophy among other vagaries were also to have the notion that it could occur to a man to act in accordance with it’s teaching, one might make out of that a queer comedy" (Frank 35). This must have been the exact idea that was going through the mind of Dostoievsky when he decided to begin writing Notes From the Underground because the underground man was not primarily a private individual but a social type (Frank 38) Notes From the Underground was originally begun as a polemic inspired by Dostoievsky’s opposition to Nihilism (Frank 36). Dostoievsky assimilates the major doctrines of Russian Nihilism into the life of his underground man; and by revealing the hopeless dilemmas in which he lands as a result, Dotoievsky intends to undermine these doctrines from within. (Frank 37).

Works Cited

Audi, Robert. The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy. New York: Cambridge University Press,1995.

Cizevskij. History of Nineteenth- Century Russian Literature. Ed. Zenkovsky, Serge A. N

Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1974.

Frank, Joseph. "Nihilism and Notes From the Underground." Fyodor Dostoevsky. Ed. Bloom, Harold. New York: Chelsea House Publishers,1988.

Miller, L. Questions That Matter: An Invitation to Philosophy. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies,1996.

Psychological

Susan Ambrosinio

Psychological Perspective of the Underground Man in "Notes From The Underground"

by Fyodor Dostoyevsky(A Chronicle of Literary Intellectual Narcissism)

Acutely sensitized by an obsessive preoccupation with his own ‘high consciousness’ and ‘intelligence’ and encouraged by a lifetime of literary pursuits, the Underground Man is a social retard who comports himself badly while trying to convince others of his ‘superiority.’ He tells the story of himself as a young man exhibiting irrational antisocial behaviors, and believing himself ‘superior’ because of his ability to reason. But from his position as an older man writing his confessions, he sees that "reason is nothing but reason and satisfies only the rational side of man’s nature, while will is a manifestation of the whole life, that is, of the whole human life including reason and all the impulses." (Dostoyevsky, page 19). He gives us his confession of how as a young man he forced himself through his own will into a crazy and tortuous experience with a few old school peers who hardly cared a fig for him. His need to get their approval and convince them of his ‘intellectual’ superiority is obsessive and pointless, because he has no real concern to establish any friendship with them but only needs them as a mirror so he can look upon his own narcissistic vision of himself. He cannot be content in his ‘perfect’ ‘literary’ world and puts himself through these antics because "boredom sets in" and it is that boredom which "sets one sticking golden pins in people." (Dostoyevsky, page 17). Sticking pins in himself seems to work best for the Underground Man. His perceptions of a conflict between reason and free-will leads him into a spitefulness, a kind of self-torture. In his essay, Notes From The Underground Presents a Romanticized View of Freedom (107), Malcolm V. Jones states, "The failure of reality to match up to the hero’s ideals draws forth in him sado-masochistic tendencies."

He also feels the need to avoid being played upon like a mere "piano key," or stomped on like an "organ stop" (Dostoyevsky, page 16). He therefore lashes out in as ridiculous a manner as possible, merely to do something other than read books. With a total lack of social graces, and any semblance of social competence clouded by an obsessive use of defense mechanisms he makes an utter fool of himself trying desperately to establish the fact of his ‘superiority’ to his old school chums.

In summary the Underground Man is an individual whose ‘high consciousness’ thwarts his every desire for action, bringing upon himself an endless turmoil of self-analysis, then doubt and confusion, followed by fantasy and irrational behavior and finally a total contradiction of all he thinks he is.

He begins with an awareness and understanding of the narrowness of pure intellectual reasoning but carries this idea to the extreme until he becomes stuck on a long and tortuous journey into frivolous ego annihilation. The Underground Man evolves into an exaggeration, a caricature of a conflicted soul, a man caught between the mathematical analogy of 2+2=4 and the free-will pleasure and artistic license of 2+2=5. The result is he becomes a confused wild-man roaming various social situations in order to declare his true self and his true ‘superiority’ but continually losing himself in humiliation to his ‘intellectual inferiors.’ He spins in confusion until all his actions result in a type of inertia and he ends up where he started— isolated in his underground hole, which is a symbol for his over rational literary mindset. It is safe there. He can retreat back to this mouse hole and remain a mouse. As a mouse in an underground hole the Underground Man describes the life of such a mouse in the following statement. "The luckless mouse succeeds in creating around it so many nastinesses in the form of doubts and questions, adds to any one question so many unsettled questions that there inevitably works up around it a sort of fatal brew, a stinking mess, made up of its doubts, emotions and of the contempt spat upon it by the direct men of action who stand solemnly about it as judges and arbitrators, laughing at it until their healthy sides ache." (Dostoyevsky, page 7).

The direct men of action referred to are men who are intellectually inferior to the Underground Man mouse. They are capable of action only because they do not feel compelled to think about and analyze all their actions. They only need to react. "Such a (person) simply dashes straight for his object like an infuriated bull with its horns down, and nothing but a wall will stop him." (Dostoyevsky, page 6)

However, despite his belief in his own superiority, the Underground Man is continually jealous of those who are ‘intellectually inferior’ to him. These bulls are not caught up in the inertia of constant self-analysis, but instead go to parties, enjoy dinners with friends, have social lives, have careers, are respected by their peers. The Underground Man is jealous of them and despises them for their ‘stupidity’, yet earnestly longs to be among them, to gain their approval, to win them over to a sense of his own ‘superiority’. But his intellectual aloofness and inability to feel compassion for his fellow humans disallows him from entering into any relationship that requires the warmth of friendly camaraderie. All contact with humans for the Underground Man is perceived as a challenge to his ego. In Part II, Chapter I, page 31, he makes the following statement with reference to his fellow humans. "There was no one like me and I was unlike anyone else, ‘I am alone and they are everyone,’ I thought." In the same chapter he also states, "I was a mere fly in the eyes of all this world, a nasty, disgusting fly— more intelligent, more highly developed, more refined in feeling than any of them, of course— but a fly that was continually making way for everyone, insulted and injured by everyone." (Dostoyevsky, page 36). How sad those words are. It is the Underground Man against the rest of the world. He sees himself as isolated by his ‘intelligence.’ He cannot merely be friendly and have a good time. He must exude his superiority,’ his ‘intellect,’ and his ‘high consciousness.’ All other humans fall short in his mind. He then hates them, imagines they do not like him, fantasizes about revenge scenarios, acts out ridiculous paranoiac theatrics, makes a fool of himself, and contradicts all his own previous statements. It almost seems to me that perhaps somewhere in the gauzy limbo-like world that characters go to after novels end, he has already put a gun to his head. But I don’t think so. He is pathetic, yes. But his pathos gives him life!

From a psychological point-of-view, he is every one of us. Granted, his antics are carried to the extreme. But it is easy to see many commonplace human characteristics in the Underground Man’s behaviors. He exhibits many classic psychological defense mechanisms— withdrawal, denial of reality, dream fantasy, self-delusion, illusions of grandeur, projection of blame on others for one’s own failures. His constant ‘intellectualization’ of his own failures is a common defense mechanism humans use all the time. The Underground Man uses escapism when he withdraws into the world of books and ideas. His inner conflict because of his acute sense of the discord between reason and free-will forces him to use fantasy as his most prevalent mechanism. He has dreams of revenge on "an officer who moved me from where I was standing to another spot and passed by as though he had not noticed me." (Dostoyevsky, page 34). The Underground Man’s perpetual low-self esteem, even in the face of his delusions of grandeur regarding his ‘intellectual superiority,’ are the cause of his obsession for a period of two years on this officer. His dream of revenge, and the ridiculous antics within which he involves himself because of this revenge fantasy, allows him to avoid facing the fact of his own social inadequacy. He obsesses on thoughts of a dual, letter writing, demands for an apology, writes a novel about the officer, plans to confront him on the street in order to refrain from stepping aside for him, and buys new clothes to make himself more presentable for this revenge scenario. All this to avoid facing the truth about his social ineptness.

Throughout the novel the Underground Man goes off into flights of fantasy, dreaming he is "riding a white horse and crowned with laurel" for example. (Dostoyevsky, page 39). Another example is taken from a long fantasy he relates in the same chapter (page 40). "I was a poet and a grand gentleman, I fell in love; I came in for countless millions and immediately devoted them to humanity, and at the same time I confessed before all the people my shameful deeds, which, of course, were not merely shameful, but had in them much that was ‘sublime and beautiful’ … Everyone would Kiss me and weep (what idiots they would be if they did not), while I would go barefoot and hungry preaching new ideas and fighting a victorious Austerlitz against obscurantists. Then the band would play a march, an amnesty would be declared, the Pope would agree to retire from Rome to Brazil; then there would be a ball for the whole of Italy at the Villa Borghese on the shores of Lake Como …." Fantasy is a common defense mechanism humans use. It helps us work through difficult times. But fantasy carried too far leads to inertia and lack of growth. The Underground Man’s fantasies suffice for living his life. He does not need much action. Real living is unnecessary. It is much safer to dream and fantasize then to do the work of successful living.

Confusion seems to be a prevalent theme throughout the novel— the confusion of the Underground Man, the confusion caused by too much philosophical thought, and the confusion caused by the conflict between reason and free-will. Part I of the "Notes," where the Underground Man speaks from his isolation and attacks liberal philosophy, is indeed very confusing. If one is not well versed in Philosophy one can easily get lost in this seemingly circular conundrum. I personally had to read it through twice before I felt I was getting a basic understanding of it. But stick to it. It is worth it. Dostoyevsky uses this confusion to make his point. That man is in a state of confusion when he is caught between reason and free-will. In his essay, Malcolm V. Jones clearly describes the Underground Man’s situation. "What is of fundamental importance is the Underground Man’s exceptional consciousness of the irreducible complexity of life and his inability to cope with it or engage in consistent and worthwhile action. His sense of impotence, alienation, resentment, self-humiliation should be understood in terms of this primary problem, an inability to find any bearings in life which are adequate to life’s complexity, to make ideal and reality connect, to discover in himself an effective idea." (104). Finding a compromise, a safe ground between the two opposites of reason and free-will, is an epic struggle for the Underground Man.

But as a reader, once one learns to bounce around in the confusion, and once one learns to flow with the innate readability of this novel, Dostoyevsky’s message becomes increasingly clear. Modern man, represented by the Underground Man, is a conflicted thing. One moment quite logical, the next so irrational.

In Part II, when the Underground Man confesses to a folly from when he was 24 years old and tries to interact with a group of his peers, the reader fully understands the chaos the Underground Man has fallen into. It is then that we realize the significance of the Underground Man’s personal interplay of philosophical satire and psychological comedy. His antics, in Part II, if viewed as a silent movie, without the advantage of his thought input, would seem like a Charlie Chaplin movie. It is laughable. But Dostoyevsky makes his point quite clear. The Underground Man, in order to find a comfort zone between reason and free-will, lives with conflict and denial, resulting in outrageous displays of aggressive spitefulness.

So does every man feel this conflict, so does all of society, all of civilization. We build churches, universities, bridges. Then we tear down what we construct with bombs and war machinery. We make human connections. Then we turn against our fellow man. As Malcolm V. Jones states, " Civilization has not made man less aggressive; it has made him more complex and increased the variety of his appetites and sensations." (110)

It is my belief that, in the final analysis, man is indeed an impotent being if he is unable to embrace the true grain of his God-like-Spirit (my words). Without compassion, human warmth, and a sense of a higher power, man falls into hopeless folly. Humbug! to reason, humbug! to the romantic notions of art, humbug! to "the sublime and the beautiful" humbug to science, humbug to philosophy. Man’s innate free-will will lead him astray and only love and compassion, which is man’s true sense of the higher power, can bring him back.

The Underground Man gets close to this feeling when he tries to help the prostitute. He speaks of the nature of human love in the family, where love begins. He also refers to God. He speaks of "love and God," of "the blessing of God," of "love as a holy mystery," of "the union of souls."(Dostoyevsky, page 66-67). In the next chapter he says, "Love! But that’s everything you know, it’s a priceless diamond." (Dostoyevsky, page 69). But his speech to Liza the prostitute is shallow. It is merely a speech, lacking the true feeling necessary to make it real. His words themselves are real, not his motivation. In chapter 6 the Underground Man states, "I began to feel myself what I was saying and warmed to the subject. I was already longing to expound the cherished ideas I had brooded over in my corner." Yes what he says is merely ideas, not true feeling. His words stem from what he has read in a book, not from what he has felt in his heart. He only feels it after he has read about the idea of it. His feelings do not stem from experience in the world. At the end of chapter 6, on page 68, Liza says, "Why, you . . . speak somehow like a book."

In chapter 7 the Underground Man goes off on three pages of preaching a love fantasy to Liza. He is so caught up in the literary aspect of his fantasy and its boost to his own ego, that he misses his chance to connect to the one human being that tries to get close to him.

Later he dreads the possibility that Liza might come to visit him. He fears that "I shall begin bowing and scraping before her and pulling my dressing-gown round me, I shall begin smiling, telling lies. Oh the beastliness!" (Dostoyevsky, page 76). The possibility of a loving relationship with a human is beastly to him. It is only late at night when he is sure she will no longer come that he can think fondly of her, perhaps even love her. "I felt particularly bold and cheerful after nine o’clock." (Dostoyevsky, page 77).

In his ‘after-nine-o’clock’ fantasy he is able to "notice that she loves me, loves me passionately. She flings herself at my feet and says that I am her savior." (Dostoyevsky, page 77-78). Then he retreats back into his literary escapism. "I launch off at that point into European, inexplicably lofty subtleties a la George Sand, but now, now you are mine, you are my creation, you are pure, you are good, you are my noble wife." (Dostoyevsky page 78). Ha! What a laugh! When she finally does visit him, he falls apart, he insults her, admits his narrow selfish lack of human empathy to her, falls down weeping in self pity, in short humiliates himself. And when she feels sympathy for him, he pays her the ultimate insult, he gives her cold cash for her efforts. What better way to destroy the threat of any feeling she might harbor for him?

The Underground Man loses his last chance to redeem himself. He goes back to his hole to wallow in his literary intellectual narcissism. There he remains until he is forty years old and begins to tell his confessions.

One of the last statements the Underground Man makes in the final chapter of the book sums up his situation perfectly. "I have spoiled my life through morally rotting in my corner, through lack of fitting environment, through divorce from real life, and rankling spite in my underground world." He further adds "we are all divorced from life, we are all cripples, every one of us, more or less." (Dostoyevsky, page 90).

One may wonder just why Dostoyevsky chose the Underground Man as the hero of this novel. Please consider the statement by Edward Wasiolek in his ‘Dostoyevsky: Major Fiction.’ "Before the implacable laws of nature, which reason discerns and by which it destroys freedom and erects the universal social anthill, the Underground Man will stand up, with no weapon but his puny will, put his arms akimbo, stick out his tongue, and give the whole edifice one shattering kick." (39). Wasiolek further adds, "The Underground Man does not want to be defined, and cannot be defined. At every moment he redefines himself by contradiction and denial. Why does he do this? Because such denial and contradiction and such constant and continual redefinition, are a pledge of his freedom." (43) In this aspect we must respect him.

WORKS CITED

"Notes From The Underground" Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Dover Thrift Editions, Dover Publications, Inc., New York, 1992

"Notes From The Underground Presents a Romanticized View of Freedom," Malcolm V. Jones, an essay from "Readings On Fyodor Dostoyevsky" Editor Bruno Leone, The Greenhaven Press Literary Companion To World Authors, Greenhaven Press, San Diego, California 1998

"Dostoyevsky: The Major Fiction" Edward Wasiolek, Massachesettes Institute of Technology Press, Cambridge, Massachusettes, 1964

FURTHER READING

"Dostoyevsky And Romantic Realism," Donald Fanger, Phoenix Books, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London, 1965

"Dostoyevsky: His Life and Work" Ronald Hingley, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York 1978

"Modern Critical Views: Fyodor Dostoyevsky" Edited an with an introduction by Harold Bloom, Chelsea House Publishers, New York, Philadelphia, 1988

Back to the top Questions to Consider 1. What is Dostoevsky’s purpose in showing the dualistic nature of man?1. What are the meanings of some of the metaphors in the novel.

For example:

the underground

the ‘sublime and the beautiful’

putting out one’s tongue

making a long nose

the bull, the mouse, the fly, the sheep, ants

twice two makes four

the toothache

the soap bubble

the piano key

the organ stop

the Crystal Palace

the chicken coop or hen house

sticking golden pins

the road

the clock

How did D's first trip to Europe influence Notes?

Did D feel empathy to the peasants or superior to them?

Does the description of the Crystal Palace represent D's views of the upper classes?

Why does he speak of "wet snow" when there is no snow in the story?

[Hit Counter]

Revised ____