|

Lesson Plan/Teaching Notes

A great place to start background research on Dickinson is to use the Dickinson Electronic Archives, an online compendium of manuscripts, essays, and other information on Dickinson and her times.

Growing up amidst the second Great Awakening – a time of religious fervor swept through Amherst – when most of her friends “converted.” She resisted this. That said, her

There’s long been the idea that she lived as a recluse, sheltered from the world.

Yes and no.

Yes, she spent the second half of her life primarily with family and primarily in her room, but this was a gradual process. Her surviving family, Austin and Lavinia, specifically noted that Emily was no different than others.

No to the sheltered from the world. She read deeply, and was intimately aware of

Her married brother (Austin) carried on a prolonged affair with a married women for years. The daughter recalls that this involved being locked up in a room with her all afternoon with no one allowed to disturb them.

I say this to show that while her circle was close, it encompassed much experience.

A fine short biography (and general commentary on her poetic method) can be found in the Dictionary of Literary Biography article.

The Poems

Lived only 56 years – but wrote around 1800 poems, which she collected into bundles ('fascicles'), that were discovered at her death by her sister, Lavinia, and were first published in 1891. In 1955, Edward Johnson published the first scholarly edition – which retained Dickinson’s idiosyncratic capitalization, syntax, and punctuation.

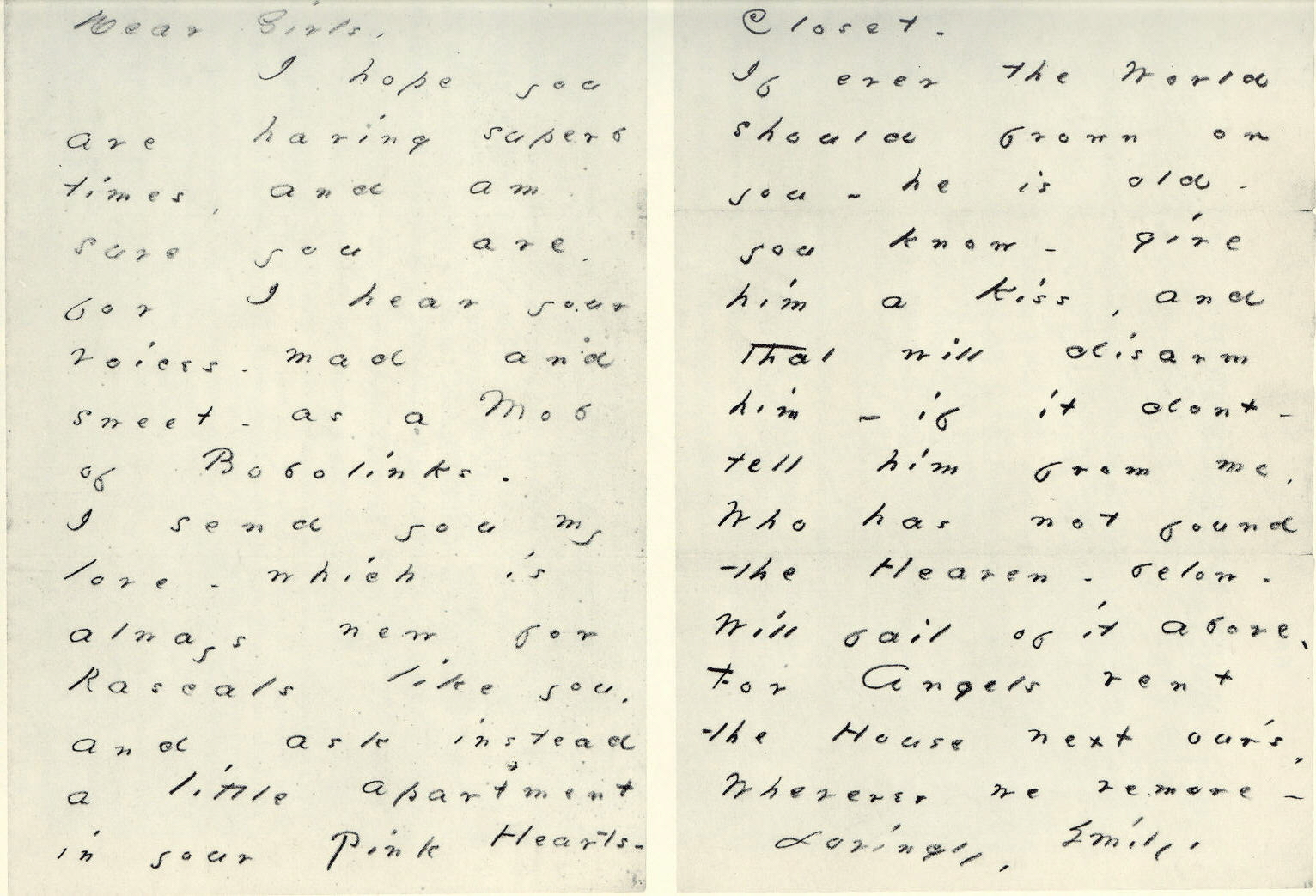

Only 10 her poems were published in her lifetime, but many of them were sent in letters.

The issues of the Springfield Republican included here contain poems composed by Dickinson or War news important to Dickinson. The issues which include her poems are those of May 4, 1861 with "May Wine" ("I taste a liquor never brewed -"); March 1, 1862 with "The Sleeping" ("Safe in their Alabaster Chambers -"); March 30, 1864 with "Sunset" ("Blazing in Gold, and quenching in Purple"); and March 9, 1864 with "Flowers" ("Flowers - Well - if anybody"). Also included with these issues are articles that directly surround her poems and any articles with Civil War news. Lundin notes that some of the poems came from letters to Bowles and that they "were published without her permission" (105).

On her love of words – and punctuation

Letter to friend

“We used to think, Joseph, when I was an unsifted girl and you so scholarly that words were cheap & weak. Now I don’t know of anything so mighty. There are [those] to which I lift my hat when I see them sitting princelike among their peers on the page. Sometimes I write one, and look at his outlines till he glows as no sapphire” (qtd. In Sewall 423)

In an early valentine letter, after comparing herself to the biblical Judith, she writes

“That’s what they call a metaphor in our country. Don’t be afraid of it, sir, it won’t bite.”

And the reason she needs to resort to metaphor? Similar to Thoreau “But the world is sleeping in ignorance and error, sir, and we must be crowing cocks, and singing larks, and a rising sun to awake her; or else we’ll pull society up to the roots, and plant it in a different place. We’ll build Alms-houses, and transcendental State prisons, and scaffolds – we will blow out the sun, and the moon, and encourage invention. Alpha shall kiss Omega – we will ride up the hill of glory – Hallelujah, all hail!” (qtd. In Sewall 420)

“The proper use of the dash is to express a sudden stop, or change of the subject; but, by modern writers, it is employed as a substitute for almost all of the other marks; being used sometimes for a comma, semicolon, colon, or period; sometimes for a question or an exclamation, and sometimes for crotchets and brackets to enclose a parenthesis” (qtd. In Sewall 349n)

Note also the following on capitals “Any words, when remarkable emphatical, or when they are the principal subject of the composition, may begin with capitals” (qtd. In Sewall 350n

Her brother and sister also used dashes profusely in their letters. (Sewall 350n)

General Approach to Dickinson's Poetry

Dickinson's work is very indivdual -- yet open to all who take the time to interpret it. Below find some general guidelines that should help you when reading her poetry

From http://guweb2.gonzaga.edu/faculty/campbell/enl311/dickpoems.html

1. Speaker. Who is the speaker? What person (first, second, third) is ED speaking in? If it is the first person plural, with whom has she aligned herself? To whom is the poem addressed?

2. Setting or Situation. What is the setting? Real? Abstract? What about the situation? Is there action in the poem? What is it?

3. What are the verbs? What is their tense? Their mood (indicative, subjunctive, interrogative)? In what ways does their syntax vary from what you expect? Are any of them archaic or unusual?

4. What is the form of the poem? Closed? Open? What is the meter? the rhyme scheme? Where does ED depart from these patterns and forms? Why?

Dickinson is noted for her use of special kinds of rhyme. Where does she use the following, and for what effect?

a. slant rhyme: a kind of consonance (relation between words in which the final consonants in the stressed syllables agree but the vowels that precede them differ: add/read, up/step, peer/pare, while/hill).

b. eye rhyme: rhyme that appears correct from the spelling but is not so from the pronunciation, such as watch/match, love/move, through/enough.

c. true rhyme: identity of terminal sound between accented syllables, usually occupying corresponding positions in two or more lines of verse. The correspondence of sound is based on the vowels and succeeding consonants of the accented syllables, which must, for a true rhyme, be preceded by different consonants. Thus "fan" and "ran" constitute a true rhyme because the vowel and succeeding consonant sounds ("an") are the same but the preceding consonant sounds are different.

6. What elements are repeated? Inverted? Why? What instances of repetition does she use? What is the effect of the repetition?

7. What figures of speech does the poem contain? metaphor? metonymy? synecdoche? personification? extended metaphor? What kind of figure does she use as a comparison (vehicle)? Where has she used this before and with what kinds of meaning or resonance?

8. What kinds of images does she use? olfactory? tactile? visual? auditory? thermal? Characteristic Dickinson images include patterns of light/dark, bee/flower, mind/body, life/death. Do these occur here? In what combination?

9. Does the poem have an effective, striking, or climactic moment? Does it come to some kind of resolution? What kind? What recognition does the speaker's persona achieve, or does the poem chronicle simple description and observation?

10. Tone. What is the tone of the whole? Solemn? Playful? Irreverent? Mournful? Objective? What is Dickinson trying to convey?

11. Tradition. In what ways does she allude to other works or poetic traditions? In what ways might this poem be an "answer" to another author?

12. Rhetorical figures. Where does Dickinson use paradox? hyperbole? anaphora? apostrophe? litotes? Why does she use them?

13. Language. Note any words that are used in an archaic, special, or unusual way, especially words of three syllables or more. (These are less common in Dickinson's work than one- and two-syllable words.) Look them up in the dictionary, being careful to note obsolete or secondary meanings as well as primary ones.

Group work: Emily Dickinson Class Three

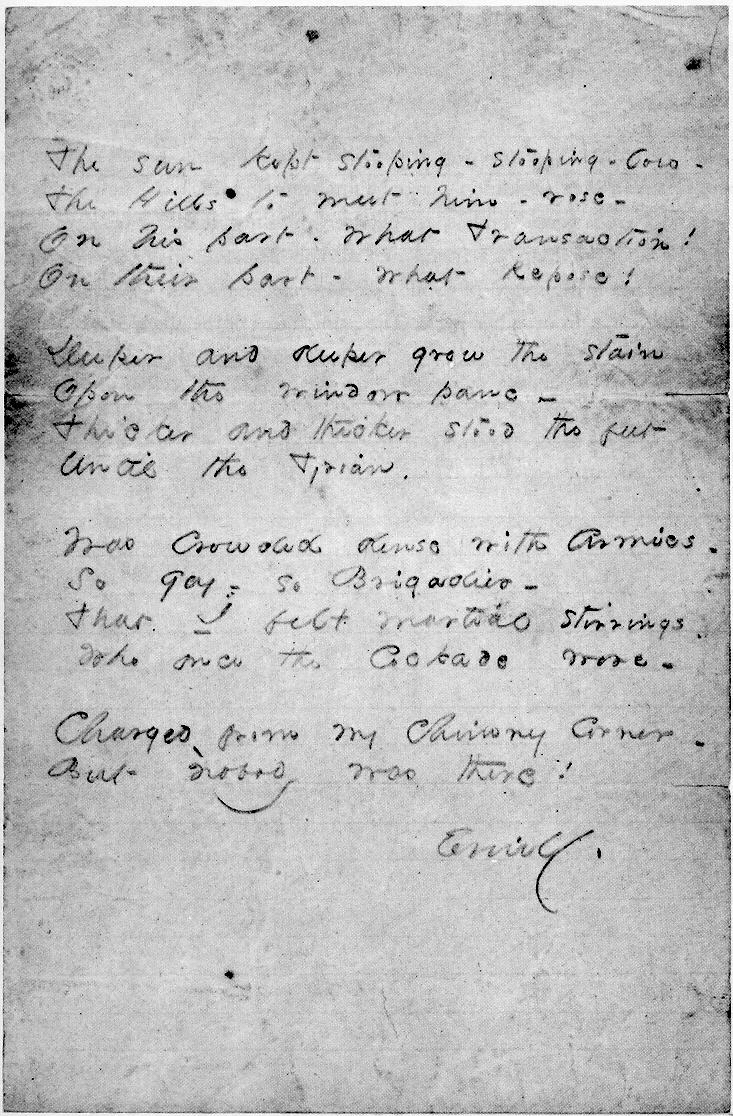

Manuscript of Dickinson's poem "The Sun Kept Stooping -- Stooping -- Low" #152

(From American Literary Autographs)

Quotes from critics

Last Revised November 2005

David Bordelon