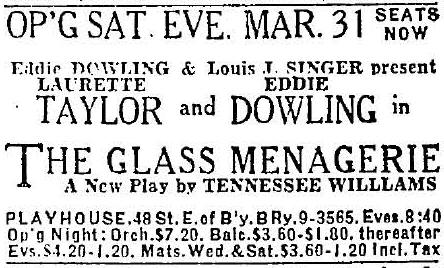

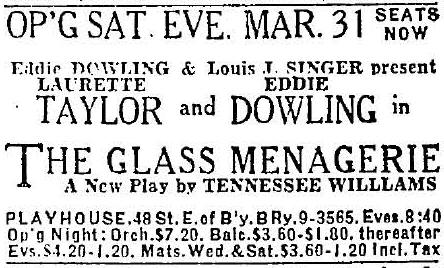

Advertisement for an early performance of The Glass Menagerie -- note the prices

The Glass Menagerie

We move here from reading short stories and novels to reading drama -- which is a bit of an oxymoron: how can you "read" something that supposedly only exists when it is performed? And that is one of the dilemmas of reading a play, as opposed to watching it unfold on a stage in a darkened room surrounded by strangers.

Advertisement for an early performance of The Glass Menagerie

-- note the prices

Remember in a play there is no third person to reveal the inner workings of a character's mind -- unless the writers uses a convention of a soliloquy (an actor speaking directly to the audience which understands that the character is revealing what is on his/her mind -- Tom at the beginning and throughout this play) or a character whose purpose is to comment on the actions of other characters (the stage manager in Our Town for instance).

Thus, the dialogue, as in real life, means all.

As we've seen, particularly in Carver's "Cathedral," characters reveal themselves by what they say, and here the revelations come fast and furious. Pay attention to the stage directions and be sensitive to the different tones words can have in a conversation.

And as we've seen in The Things They Carried, writers delight in subverting reader's expectations, so pay attention to actions of seemingly innocuous characters like "a nice, ordinary, young man" (1974) and how they may comment on much broader concerns.

Written in 1945, the play takes for granted that its audience will catch many

of the allusions. For instance, in Tom's first speech, he says "In Spain

there was Guernica!" (1975) to which you may respond "huh?" or "that's nice" or,

if you've taken Art History II "Didn't Matisse do a painting with that name."

Actually, it was

Picasso.

And it's not so much the painting itself as the impetus behind the painting that Tom/Williams is alluding to. The painting itself is based on the infamous 1937 attack on a civilian town of the same name during the Spanish Civil War. General Franco (fascist leader of Spain) invited the Germans in to try out their new technique of mass aerial bombardment and terrorizing non-combatants. Its inclusion in the play seems to symbolize the inaction of Americans in the face of the Great Depression. "In Spain," faced with an economic system that kept most workers at a subsistence level, the proletariat rose up, regardless of the odds (pitchforks and shotguns against tanks and machine guns), and tried to defeat the fascists (read Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls for a more developed American [fictional] take on this). What was the American response to similar economic travails, a time when our "fingers [were being] pressed forcibly down on the fiery Braille alphabet of a dissolving economy" (1975)?

Other references come fast and furious: "Berchtesgaden" and "Chamberlain" (1993) are both references to WWII (for which the Spanish Civil War was a practice run -- as the audience would know), the former being a retreat for Hitler (a German version of Camp David), the latter being the British Prime Minister when Hitler was gobbling up the Europe -- and the rest of the world was reluctant to challenge him.

And a play that opens with explicit references to class strife, both local (in America) and global (Spain), and to war means that the audience needs to pay attention to the "p" word: politics. Not in the boring and fractious republican/democrat sense, but in the how people and governments interact sense. Consider, for example, that loaded term "democracy." Just what does it really mean? That's one of the questions posed by the play.

Finally, remember that this is, again as Tom (by the way, Tennessee Williams name was really Thomas . . . and he had a mother from the South . . . and a sister that was mentally unstable . . . and a drifter of a father . . .) notes a "memory play" (1975), and as Things made clear, one thing that is not clear is memory. As a character in Ngugi Wa Thiong'o's brilliant novel Petals of Blood notes, "For what are recollections but fiction, products of a heated imagination?" (191). This heat, as we've seen throughout the semester, leads to gripping narratives that slake our thirst for sensation, philosophical ruminations that plumb the depths of our minds and souls, observations on the folly of humans and our relationships . . . in other words, the whole host of images and ideas that paint the canvas of life. We are, after all, artists in the gallery of our lives, right?

Sit back and enjoy the show.

Questions to mull over while reading the play

when is the play set?

Why is it valid to discuss the social background of this play?

"Franco Triumphs" -- why is this detail included? -- Need to research on Franco.

Could this be a play about democracy? "Knowledge -- Zzzzp! Money -- Zzzzp! -- Power! That's the cycle democracy is built on!" (2015) is this true? Does it matter who is saying it? (cf. "I'm pretty clumsy with things")

"quiet desparation" Thoreau v. adventure (1550) But is it as simple as inaction = bad, action/adventure = good? What is all the action he talks about relate to "all the world is waiting for bombardments!" (1993)

What distinctions does the play make between "instinct" v. civilization

Annunciation: Angel Gabriel telling Mary (a virgin) she would conceive. Here, it's the gentleman caller.

Candelabrum burned -- why?

What is the play suggesting about reality v. illusion? Who lives in the reality and who lives in illusion? Consider Amanda's comment to Tom: "You live in a dream, you manufacture illusions!" -- while true, why is she so made at Tom?

If this is supposed to be an "unrealistic" play, is it convincing? Do the characters and actions seem convincing?

Is this a tragedy? Who's the hero? What's the flaw? What's the crisis?

Group Questions

Work Cited

Wa Thiong'o, Ngugi. Petals of Blood. New York: Penguin, 1977.

Williams, Tennesee. The Glass Menagerie. Literature: An Introduction to Fiction, Poetry, and Drama.

Ed. X. J. Kennedy and Dana Gioia. New York: Longman, 1999. 1972-2022.

Image Credits

Ad for The Glass Menagerie. New York Times. 18 March 1945: X2. Proquest Historical Newspapers.

Online. Ocean County College Library. 14 October 2004.