Lesson

Plans

Lesson Plans

Course Documents Links

Home Page

Quick

Links

Library

Links

Citing

Sources

The Meursault Investigation

http://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/320/cpsprodpb/53E0/production/_88427412_kameldaoud.jpg

Kamel Daoud

Terms to Know | General

Questions | Group

Questions

| Criticism

| Pictures

| Links

Country/Date

Written/Published

Algeria-Written in French/2013

Mid-Term Review

Make sure you know the basic tenets of each of these intellectual/literary movements.

The Enlightenment | Romanticism | Realism | Modernism | Absurdism | Postcolonialism | Postmodernism | Metafiction

Musa: Used for the prophet Moses in the Quran. Also has the meaning of "drawn from water" or "taken from water"

Harun: Brother of Moses: prophet; high priest

Postcolonial

literature

Literatures in English emerging from the anglophone world outside

Britain, Ireland, and the United States constitute an important and

growing body of writing, often referred to as postcolonial or world

literature in English. Many of the regions and countries from which

this literature emerges—the Caribbean, the Indian sub‐continent, West

Africa, in particular Nigeria and Ghana, East and southern Africa, and

Australasia and the Pacific islands—were once colonies of Britain, and

now form part of the Commonwealth, hence the term ‘postcolonial’. It

is, however, beset with contradictions, not least in respect of the

chronological limits of the postcolonial: did empire end with Indian

independence in 1947, or in 1956 with Suez, or was it later, when many

of the African countries gained their independence?

Nevertheless, the term ‘postcolonial literature’ is considered to be

the most convenient way of embracing the diverse body of literary

responses to the challenges presented by decolonization and the

transitions to independence and after. Postcolonial literature might be

broadly defined as that which critically or subversively scrutinizes

the colonial relationship, and offers a reshaping or rewriting of the

dominant meanings pertaining to race, authority, space, and identity

prevalent under colonial and decolonizing conditions.

Many assumptions that are central to postcolonial literary studies

emanate from the influential work of the critic Edward Said, in

particular his Orientalism

(1978), and Culture and

Imperialism (1993).

These include the critical perception that cultural representations (of

‘savages’ and ‘cannibals’; or of primitive Africa or the exotic East)

were fundamental first to the process of colonizing other lands, and

then again to the process of obtaining independence (imaginative and

otherwise) from the colonizer. As Joseph Conrad was among the first to

acknowledge, in his ‘Heart of Darkness’ (1899), assuming control over a

territory or a nation meant not only exerting political or economic

power but also having imaginative command. Overturning and replacing

imperial systems of control therefore involved contesting these

European imaginative and literary versions of the colonial experience,

or as Indian‐born writer Salman Rushdie famously put it, it involved

the empire ‘writing back’.

Postcolonial literature, in seeking to awaken political and cultural

nationalism, has dwelt on popular revolts against colonial rule,

exposing the lie of the passive and indolent native; the Trinidadian C.

L. R. James has brought to the fore neglected black heroes like

Toussaint Louverture, who led the greatest slave revolt in history to

set up Haiti, the first free black republic in the West. The world‐view

of the cane-cutters of the sugar plantations and other such ‘lowly’

people, expressed in their myths and legends, is given space in

postcolonial literature, with writers like the Guyanese Wilson Harris

arguing that Amerindian mythology reveals values and perspectives as

complex and mysterious as any originating from the Graeco‐Roman or

Judaeo‐Christian traditions. There is a corresponding reappraisal of

oral expression, in riddles and proverbs and songs and stories.

Writers as diverse as Caryl Phillips, Nadine Gordimer, Peter Carey, and

Arundhati Roy acknowledge that making a postcolonial world means

learning how to live in and represent that world in a profoundly

different way.

Language is inextricably bound up with culture and identity, and as the

colonizers attempted, with varying degrees of success, to impose the

English language on subject peoples, the response from the formerly

colonized has ranged from the outright rejection of English as a medium

through which to exercise their art, to the appropriation of it with

subversive intent. After first using English as the medium for his

fiction, the Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiong'o finally decided to reject

it. For others, like the Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe, or Indian

novelists Upamanyu Chatterjee and Amit Chaudhuri, English has been a

means of uniting peoples across continents and of reaching a wider

audience than would have been possible in their mother tongues.

Caribbeanists like Derek Walcott and V. S. Naipaul have used techniques

such as switching in and out of standard English and local Creoles to

emphasize that their cultural worlds are irrevocably multicultural and

hybridized. Some see English as having become detached from Britain or

Britishness. They claim the language as their own property, for they

have moulded and refashioned it to make it bear the weight of their own

experience.

There has been celebratory and affirmative acknowledgement of women's

experiences, following painful legacies of ‘double’ and in some cases

‘triple colonization’ (as women, black, lower class, lower caste,

‘queer’, etc.) under empire. The distinguished and burgeoning list of

postcolonial women writers includes Jean Rhys, Anita Desai, Bessie

Head, Doris Lessing, Olive Senior, Nadine Gordimer, and Tsitsi

Dangarembga.

Postcolonial literature worldwide has registered the impact of

modernist and also postmodernist traditions of Anglo‐American writing.

The montage effects and mythic adaptations of Anglo‐American modernist

poetry, for example, were enthusiastically adopted but also extended

and enriched from local sources by writers such as Christopher Okigbo

and Wole Soyinka. The subversive, playful techniques of metropolitan

postmodernism have been appropriated by postcolonial writers in order

to dramatize the unstable, provisional, and ever‐shifting constitution

of identities in the aftermath of empire, as in the work of Michael

Ondaatje and Dambudzo Marechera. Postcolonial literature, as writers

like Rushdie and Derek Walcott recognize, has itself formed and

informed modernist and postmodernist techniques.

http://www.postcolonialweb.org Postcolonial Web: resource for

postcolonial literature.

"postcolonial literature." The Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature, Oxford Reference, edited by Dinah Birch and Katy Hooper. Oxford University Press, 2012. Accessed 3 Mar. 2018.

Questions a post-colonial critic asks (links to page on our site)

Postmodernism

A disputed term that occupied much late 20th-century debate about

culture from the early 1980s. In its simplest and least satisfactory

sense it refers generally to the phase of 20th-century Western culture

that succeeded the reign of high modernism, thus indicating the

products of the age of mass television since the mid-1950s. More often,

though, it is applied to a cultural condition prevailing in the

advanced capitalist societies since the 1960s, characterized by a

superabundance of disconnected images and styles—most noticeably in

television, advertising, commercial design, and pop video. In this

sense, promoted by Jean Baudrillard and other commentators,

postmodernity is said to be a culture of fragmentary sensations,

eclectic nostalgia, disposable simulacra, and promiscuous

superficiality, in which the traditionally valued qualities of depth,

coherence, meaning, originality, and authenticity are evacuated or

dissolved amid the random swirl of empty signals.

As applied to literature and other arts, the term is notoriously

ambiguous, implying either that modernism has been superseded or that

it has continued into a new phase. Postmodernism may be seen as a

continuation of modernism’s alienated mood and disorienting techniques

and at the same time as an abandonment of its determined quest for

artistic coherence in a fragmented world: in very crude terms, where a

modernist artist or writer would try to wrest a meaning from the world

through myth, symbol, or formal complexity, the postmodernist greets

the absurd or meaningless confusion of contemporary existence with a

certain numbed or flippant indifference, favouring self-consciously

‘depthless’ works of fabulation, pastiche, bricolage, or aleatory

disconnection. The term cannot usefully serve as an inclusive

description of all literature since the 1950s or 1960s, but is applied

selectively to those works that display most evidently the moods and

formal disconnections described above. In poetry, it has been applied

most often to the work of the New York school and to Language poetry;

in drama mainly to the ‘absurdist’ tradition; but is used more widely

in reference to fiction, notably to the novels (or anti-novels) and

stories of Thomas Pynchon, Kurt Vonnegut, Italo Calvino, Vladimir

Nabokov, William S. Burroughs, Angela Carter, Salman Rushdie, Peter

Ackroyd, Julian Barnes, Jeanette Winterson, and many of their

followers. Some of their works, like Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow

(1973)

and Nabokov’s Ada

(1969), employ devices reminiscent of science

fiction, playing with contradictory orders of reality or the irruption

of the fabulous into the secular world.

Opinion is still divided, however, on the value of the term and of the

phenomenon it purports to describe. Those who most often use it tend to

welcome ‘the postmodern’ as a liberation from the hierarchy of ‘high’

and ‘low’ cultures; while sceptics regard the term as a symptom of

irresponsible academic euphoria about the glitter of consumerist

capitalism and its moral vacuity. See also post-structuralism.

Baldick, Chris. "postmodernism." The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Oxford Reference, OUP, 2015. Accessed 3 Mar. 2018.

Metafiction

Fiction that draws attention to and directly comments upon its status

as fiction. Most often this takes the form of an intrusion of the

‘author’ into the work. One of the earliest and most celebrated cases

of metafiction is Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy

(1760–7), which has

the author commenting frequently on his failure to get on with telling

the story. But it can also take the form of a work of fiction about

either the reading or writing of fiction, as one finds (again quite

famously) in Italo Calvino’s Se

una notte d’inverno un viaggatore

(1979), translated as If

on a Winter’s Night a Traveller (1981). The

device is more common in late twentieth-century fiction writing than it

is in earlier periods and for this reason is often associated with

postmodernism, although there is no direct correlation between the two.

The device can also be witnessed in film and television.

Buchanan, Ian. "metafiction." A Dictionary of Critical Theory. Oxford Reference, OUP, 2018. Accessed 3 Mar. 2018.

Robinson Crusoe

The Life and Strange and Surprizing Adventures of

A novel by Daniel Defoe, published 1719. The story was in part inspired

by the adventures of Alexander Selkirk, who had joined a privateering

expedition under William Dampier, and in 1704 was put ashore after a

quarrel on one of the uninhabited islands of the Juan Fernández

archipelago. He was rescued in 1709 by Woodes Rogers (1679–1732). The

story was told by Richard Steele in The Englishman

(1713),

and elsewhere. Defoe's novel (told, like all his novels, in the first

person, and presented as a true story) is vastly more vivid, detailed,

and psychologically powerful, giving an extraordinarily convincing

account of the shipwrecked Crusoe's efforts to survive in isolation.

With the help of a few stores and utensils saved from the wreck and the

dedicated exercise of labour and ingenuity, Crusoe builds himself a

refuge, maps the island, domesticates goats, sows crops, and constructs

a boat. Suffering from dreams and illness, he struggles to accept the

workings of Providence, and has disturbing encounters with cannibals

from other islands, from whom he rescues the man he later names

‘Friday’. After 28 years, an English ship with a mutinous crew arrives;

by some delicate management Crusoe subdues the mutineers, and returns,

finally prosperous, to Britain. In The Farther Adventures of

Robinson Crusoe (1719), Crusoe revisits his island, is

attacked by a fleet of canoes on his departure, and loses Friday in the

encounter. Serious Reflections…of Robinson Crusoe…with his

Vision of the Angelick World,

offering a pious and allegorical interpretation of the adventures,

appeared in 1720. The influence of the Robinson Crusoe story has been

enormous. The book had immediate and permanent success; it was pirated,

adapted, and abridged in chapbooks, translated into many languages, and

inspired many imitations, known generically as ‘Robinsonnades’,

including Philip Quarll, Peter Wilkins, and The Swiss Family

Robinson. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (in Émile)

recommended it as the first book that should be studied by a growing

boy, S. T. Coleridge praised its evocation of ‘the universal man’, and

Karl Marx in Das Kapital used it to illustrate

economic

theory in action. It was extremely popular with male readers of the

19th century, being affectionately remembered by William Wordsworth,

Lord Macaulay, John Stuart Mill, George Borrow, Robert Louis Stevenson,

and John Ruskin. The novel has also inspired many artists and

film-makers. More recently it has been seen as an apologia for, or an

ironic critique of, economic individualism, capitalism, and

imperialism; a study in alienation; and an allegorical spiritual

autobiography. See Ian Watt, The Rise of the Novel

(1957); Pat Rogers, Robinson Crusoe (1979);

Michael Seidel, Robinson Crusoe: Island Myths and the Novel

(1991); David Blewett, The Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe

(1995).

"Robinson Crusoe." The Oxford

Companion to English Literature, Oxford Reference,

edited by Dinah Birch, Oxford University Press, 2009. Accessed

5 Mar. 2018.

Questions to mull over as you interpret the story

- Opening sentences: connections? Explain

- Why open in a bar?

- Why the name Musa?

- How are the family relationships similar and different in Meursault from Stranger?

- How are the relationships between citizens and the justice system similar and different in Meursault from Stranger?

- Love of a woman: how is Harun's love for Meriem

similar to Meursault's love of Marie? How is it different?

- that was romantic love -- what about maternal love?

- How does The Meursault blur the line between fiction and reality? How could the novel be a comment on our narrative understanding of the world?

- In an interview, Daoud states that "Ever since the Middle Ages, the white man has the habit of naming Africa and Asia’s mountains and insects, all the while denying the names of the human beings they encounter. By removing their names, they render banal murder and crimes. By claiming your own name, you are also making a claim of your humanity and thus the right to justice" (Zaretsky). How does providing Camus' "Arab" with a name amounting to justice?

- Would this novel work without The Stranger?

- If the sun was the primary symbol in The Stranger, what's the primary symbol here? Similarities? Differences?

- Use the questions that a postcolonial critic asks to deepen your understanding of the novel.

- How do you think Meursault can be classified as a work of metafiction? How does looking at it through this critical lens deepen our understanding of the work?

- How do you think Meursault can be classified as a post modern work? How does looking at it through this critical lens deepen our understanding of the work?

- Both novels are first person: why? How would it be different if narrated in third person?

- What do you make of the repetitions -- even of actual quotes from The Stranger -- in Meursault? Do they distract or amplify or ____?

- What are the similarities in the murders in the novels? Differences?

- How are the legal systems similar in both works? Different?

- How does Harun feel about his fellow Algerians?

- What does the novel suggest about the power of language to control the colonized? (see questions on postcolonial: 33; 89-90*; 128*

- What, more generally, does the novel suggest about the power of narrative? (this connects to metafiction) 16; 37; 57; 84; 121*; 132;

- Could this also be a book about an existentialist worldview?

Quotes to mull over:

- “I’m going to do what was done in this country after Independence: I’m going to take the stones from the old houses the colonists left behind, remove them one by one, and build my own house, my own language. The murderers words and expressions are my unclaimed goods” (2)

- "the murder he committed seems like the act of a disappointed lover unable to possess the land he loves” (3)

- “What hurts me every time I think about it is that he killed him by passing over him, not by shooting him” (5)

- “Without realizing it, in years before I learned to read, I rejected the absurdity of his death, and I needed a story to give him a shroud” (21)

- “recently they’ve been closing all the bars in the country, and all the customers are like trapped rats, jumping from one sinking boat to another. In when we get down to the last bar, there will be a lot of us, old boy, you have to use our elbows. That moment will be the real last judgment” (25)

- “In her language, she spoke like a prophetess, recruited extemporaneous mourners, and cried out against the double outrage that consumed her life: husband swallowed up by air, a son by water. I had to learn a language other than that. To survive. And it was the one I’m speaking at this moment. Starting with my presumed 15th birthday, when we withdrew to Hadjout, I became a stern in serious scholar. Books in your hero’s language gradually enabled me to name things differently and organize the world with my own words” (37)

- "everybody in the neighborhood knew the whole was empty, new mama filled it with her prayers in an invented biography. That cemetery was the place where I awaken to life, believe me. It was where I became aware that I had a right to the fire of my presence in the world – yes, I had a right to it summation point – despite the absurdity of my condition, which consisted in pushing a corpse to the top of the hill before it rolled back down endlessly. Those days, the cemetery days, for the first days when I turned to pray, not toward Mecca but toward the world” (47)

- “we have a confession, written in the first person, we have no evidence to prove him or so’s guilt; his mother never existed, for him least of all; Musa was an area replaceable by thousand others of his kind, or by a Crow, even, or read, or whatever else; the beach has disappeared, the race by footprints or agglomerations of concrete; the only witness was a star, namely the sun; the plaintiffs were illiterate, and they moved out of town; and finally the trial was a wicked travesty put on by idle colonials. What can you do with the man who meet you on a desert island and tells you that yesterday he killed a certain Friday? Nothing” (49)

- “this story takes place somewhere in someone’s head, in mind and in yours and in the heads of people like you. In a sort of beyond” (57)

- “Arab. I never felt Arab, you know. Arab–ness is like Negro–ness, which only exists in the white man’s eyes” (60)

- “What’s inexplicable is not only the murderer but also the fellow’s life. He’s a corpse that magnificently describes the quality of the light in this country while stuck in some hereafter with no gods and no Hells. Nothing but blinding routine. His life? If he hadn’t killed in written, nobody would have remembered him” (63)

- “After independence, the more I read of your hero’s work, the more I had the feeling I was pressing my face against the window of a big room where a party was going on that neither my mother nor I had been invited to” (64)

- More to come

Day 2

- In an interview, Daoud states that "Ever since the Middle Ages, the white man has the habit of naming Africa and Asia’s mountains and insects, all the while denying the names of the human beings they encounter. By removing their names, they render banal murder and crimes. By claiming your own name, you are also making a claim of your humanity and thus the right to justice" (Zaretsky). How does providing Camus' "Arab" with a name amount to justice?

- Would this novel work without The Stranger?

- How does this quote address the absurd? “This story takes place somewhere in someone’s head, in mine and in yours and in the heads of people like you. In a sort of beyond” (57). First define the absurd, then connect that definition to your explanation of the quote.

- How does the definition of postcolonialism cited above and the questions that a postcolonial critic asks deepen your understanding of the novel?

- Review of novel in The New York Times: final paragraph explains the existential dilemma that Daoud lives with.

- Doud "What to do When Your Colonizer Apologizes" New York Times. 15 October 2018.

- Interview with Dauod: Middle East Eye

- Interview with Dauod: Los Angeles Review of Books

- Zerofsky, Elizabeth. "An

Algerian rebuke to "The Stranger'." The New Yorker. Accessed

13 March 2015.

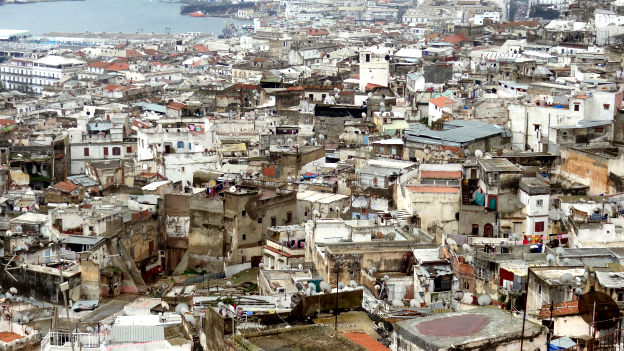

Algiers today

http://www.dagimages.fr/photos-algerie/alger1332.jpg

Links

© 2010 David Bordelon