Lesson

Plans

Lesson Plans

Course Documents Links

Home Page

Quick Links

Library Links

Citing Sources

Madame Bovary

General Questions | Group Questions | Criticism | Pictures | Links

Country/Date Written/Published

France/1851-56/1857

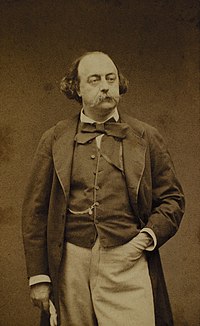

Gustave Flaubert

from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gustave_Flaubert

Terms to know

bourgeois adjective & noun M16 French. A. (1) M16 Of, pertaining to, characteristic of, or resembling, the bourgeois (see sense B below); middle-class; conventionally respectable and unimaginative, humdrum; selfishly materialistic; capitalistic, reactionary. B. noun plural same. (1) L17 Originally, a (French) citizen or freeman of a city or burgh, as distinct from a peasant or a gentleman. Now, any member of the middle class. (2) L19 In Communist or socialist writing: a capitalist, an exploiter of the proletariat. derogatory. (3) M20 A socially or aesthetically conventional person, a philistine. derogatory.

"bourgeois adjective & noun." The Oxford Essential Dictionary of Foreign Terms in English. Ed. Jennifer Speake. Berkley Books, 1999. Oxford Reference Online. Web. 30 September 2010

Irony: A subtly humorous perception of inconsistency, in which an apparently straightforward statement or event is undermined by its context so as to give it a very different significance. In various forms, irony appears in many kinds of literature, from the tragedy of Sophocles to the novels of Jane Austen and Henry James , but is especially important in satire , as in Voltaire and Swift. At its simplest, in verbal irony, it involves a discrepancy between what is said and what is really meant, as in its crude form, sarcasm; for the figures of speech exploiting this discrepancy, see antiphrasis, litotes, meiosis . The more sustained structural irony in literature involves the use of a naïve or deluded hero or unreliable narrator , whose view of the world differs widely from the true circumstances recognized by the author and readers; literary irony thus flatters its readers' intelligence at the expense of a character (or fictional narrator). A similar sense of detached superiority is achieved by dramatic irony, in which the audience knows more about a character's situation than the character does, foreseeing an outcome contrary to the character's expectations, and thus ascribing a sharply different sense to some of the character's own statements; in tragedies , this is called tragic irony. The term cosmic irony is sometimes used to denote a view of people as the dupes of a cruelly mocking Fate, as in the novels of Thomas Hardy . A writer whose works are characterized by an ironic tone may be called an ironist. For a fuller account, consult Claire Colebrook , Irony ( 2003 ).

"irony." The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Ed. Chris Baldick. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Web. 18 October 2010 .

Realism A mode of writing that gives the impression of recording or ‘reflecting’ faithfully an actual way of life. The term refers, sometimes confusingly, both to a literary method based on detailed accuracy of description (i.e. verisimilitude ) and to a more general attitude that rejects idealization, escapism, and other extravagant qualities of romance in favour of recognizing soberly the actual problems of life. Modern criticism frequently insists that realism is not a direct or simple reproduction of reality (a ‘slice of life’) but a system of conventions producing a lifelike illusion of some ‘real’ world outside the text, by processes of selection, exclusion, description, and manners of addressing the reader. In its methods and attitudes, realism may be found as an element in many kinds of writing prior to the 19th century (e.g. in Chaucer or Defoe, in their different ways); but as a dominant literary trend it is associated chiefly with the 19th‐century novel of middle‐ or lower‐class life, in which the problems of ordinary people in unremarkable circumstances are rendered with close attention to the details of physical setting and to the complexities of social life.

The outstanding works of realism in 19th‐century fiction include Honoré de Balzac 's Illusions perdues ( 1837 -- 43 ), Gustave Flaubert 's Madame Bovary ( 1857 ), and George Eliot 's Middlemarch ( 1871 -- 2 ); and in early 20th‐century fiction Arnold Bennett 's The Old Wives' Tale ( 1908 ) and Edith Wharton 's The House of Mirth ( 1905 ). In France, a self‐consciously realist school announced itself in 1857 with the publication of Champfleury's Le Réalisme, but the term normally refers to the general convention rather than to this barely significant group. In the work of some novelists, realism passes over into the movement of naturalism , in which sociological investigation and determinist views of human behaviour predominate. Realism also established itself as an important tradition in the theatre in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in the work of Henrik Ibsen , Bernard Shaw , and others; and it remains a standard convention of film and television drama. Despite the radical attempts of modernism to displace the realist emphasis on external reality (notably in the movements of expressionism and surrealism ), realism survived as a major current within 20th‐century fiction, sometimes under the label of neo‐realism . For a fuller account, consult Pam Morris, Realism (2003).

"realism." The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Ed. Chris Baldick. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Web. 17 October 2010.

Materialism In common usage, materialism describes the privileging of material comforts over spiritual, ethical, and philosophical concerns. In its philosophical sense, materialism holds that speculative thought, social processes, and institutions are directly shaped by the physical world; as such, materialism takes issue with idealism —the belief that external reality cannot be understood apart from consciousness, or, more radically, that some ideas or categories of understanding exist prior to experience. The roots of materialist thought can be traced to India in the seventh century BCE and to ancient Greece (as represented in the thought of Leucippus, Democritus, and Epicurus). The Early Modern version of materialism is attributed primarily to Thomas Hobbes , who used principles of mechanics and geometry to ground his philosophical system. Later works by David Hume and John Locke are important contributions to the materialist tradition, while critiques by George Berkeley and Immanuel Kant contributed some of the key texts of idealism. The debate between materialism and idealism formed a central dialectic in modern thought that continues to this day.

In social thought, a significant turn in this debate was Ludwig Feuerbach and Karl Marx 's contestation of Georg Hegel 's philosophy of history. Hegel claimed to have privileged neither the subject (as in the transcendental idealism of Kant) nor the object (as in the empiricist or materialist traditions). He claimed that the development of consciousness and knowledge evolved immanently through the material conditions of history, while at the same time determining them. Marx, drawing on Feuerbach, claimed to have "stood Hegel on his head, or rather, on his feet" by arguing that changes in material conditions—most importantly in the modes of economic production—led to changes in speculative thought (as well as in legal and political systems, aesthetics, ethics, and all manner of social relations). Whether or how these "superstructural" elements in turn alter the material "base" of historical development has been at the core of debates between various schools of Marxist thought ever since (see Louis Althusser , dialectical materialism , Antonio Gramsci , and historical materialism ). The Marxist turn also gave rise to a lasting subfield in sociology —the sociology of knowledge (see Karl Mannheim ). In the theory and practice of non-Marxist social science, the materialist perspective has been carried forward by various schools of behaviorism , positivism , and realism ; it has been most directly opposed by neo-Kantianism and postmodernism.

"materialism." Dictionary of the Social Sciences. Ed. Craig Calhoun.Oxford University Press 2002. Oxford Reference Online. Web. 17 October 2010.

naturalism A more deliberate kind of realism in novels, stories, and plays, usually involving a view of human beings as passive victims of natural forces and social environment. As a literary movement, naturalism was initiated in France by Jules and Edmond Goncourt with their novel Germinie Lacerteux ( 1865 ), but it came to be led by Émile Zola , who claimed a ‘scientific’ status for his studies of impoverished characters miserably subjected to hunger, sexual obsession, and hereditary defects in Thérèse Raquin ( 1867 ), Germinal ( 1885 ), and many other novels. Naturalist fiction aspired to a sociological objectivity, offering detailed and fully researched investigations into unexplored corners of modern society—railways in Zola's La Bête humaine ( 1890 ), the department store in his Au Bonheur des dames ( 1883 )—while enlivening this with a new sexual sensationalism. Other novelists and storytellers associated with naturalism include Alphonse Daudet and Guy de Maupassant in France, Theodore Dreiser and Frank Norris in the United States, and George Moore and George Gissing in England; the most significant work of naturalism in English being Dreiser's Sister Carrie ( 1900 ). In the theatre, Henrik Ibsen's play Ghosts ( 1881 ), with its stress on heredity, encouraged an important tradition of dramatic naturalism led by August Strindberg , Gerhart Hauptmann , and Maxim Gorky ; in a somewhat looser sense, the realistic plays of Anton Chekhov are sometimes grouped with the naturalist phase of European drama at the turn of the century. The term naturalistic in drama usually has a broader application, denoting a very detailed illusion of real life on the stage, especially in speech, costume, and sets. See also verisimilitude, verismo . For a fuller account, consult David Baguley , Naturalist Fiction ( 1990 ).

"naturalism." The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Ed. Chris Baldick. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Web. 17 October 2010

Romanticism: A sweeping but indispensable modern term applied to the profound shift in Western attitudes to art and human creativity that dominated much of European culture in the first half of the 19th century, and that has shaped most subsequent developments in literature—even those reacting against it. In its most coherent early form, as it emerged in the 1790s in Germany and Britain, and in the 1820s in France and elsewhere, it is known as the Romantic Movement or Romantic Revival. Its chief emphasis was upon freedom of individual self‐expression: sincerity, spontaneity, and originality became the new standards in literature, replacing the decorous imitation of classical models favoured by 18th‐century neoclassicism . Rejecting the ordered rationality of the Enlightenment as mechanical, impersonal, and artificial, the Romantics turned to the emotional directness of personal experience and to the boundlessness of individual imagination and aspiration. Increasingly independent of the declining system of aristocratic patronage, they saw themselves as free spirits expressing their own imaginative truths; several found admirers ready to hero‐worship the artist as a genius or prophet. The restrained balance valued in 18th‐century culture was abandoned in favour of emotional intensity, often taken to extremes of rapture, nostalgia (for childhood or the past), horror, melancholy, or sentimentality. Some—but not all—Romantic writers cultivated the appeal of the exotic, the bizarre, or the macabre; almost all showed a new interest in the irrational realms of dream and delirium or of folk superstition and legend. The creative imagination occupied the centre of Romantic views of art, which replaced the ‘mechanical’ rules of conventional form with an ‘organic’ principle of natural growth and free development. [. . . .]

http://www.rc.umd.edu Romantic Circles: extensive scholarly resource based at University of Maryland.

"romanticism." The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Ed. Chris Baldick. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Web. 30 September 2010.

Sensationalism: in general, this refers to exaggerated actions or descriptions which transgress the bounds of accepted behavior. Sensational literature is an attempt to render such actions in prose and specifically refers to fiction and non-fiction which revels in detailed and graphic descriptions of crime, violence, or sexual matters, usually presented as "realistic" portraits of the events described. By combining graphic depiction and realism, this type of writing accentuates the horror or disgust of a given scene or series of incidents, and both shocks and attracts readers by appealing to the salacious or voyeuristic in human nature.

Sentimental novel Broadly, any novel that exploits the reader's capacity for tenderness, compassion, or sympathy to a disproportionate degree by presenting a beclouded or unrealistic view of its subject. In a restricted sense the term refers to a widespread European novelistic development that reflected the trend toward sensibility in the 18th century, which arose partly in reaction to the austerity and rationalism of the Neoclassical period. The sentimental novel exalted feeling above reason and raised the analysis of emotion to a fine art. An early example in France is Antoine-FranÇois Prévost d'Exiles's Manon Lescaut, the story of a courtesan for whom a young seminary student of noble birth forsakes his career, family, and religion and ends as a card shark and confidence man. His downward progress, if not actually excused, is portrayed as a sacrifice to love.

The assumptions underlying the sentimental novel were Jean-Jacques Rousseau's doctrine of the natural goodness of humans and his belief that moral development was fostered by experiencing powerful sympathies. In England, Samuel Richardson's sentimental novel Pamela was recommended by clergymen as a means of educating the heart. In the 1760s the sentimental novel developed into the "novel of sensibility," which presented characters possessing a pronounced susceptibility to delicate sensation. Such characters were not only deeply moved by sympathy for others but also reacted emotionally to the beauty inherent in natural settings and in works of art and music. The prototype was Laurence Sterne's Tristram Shandy (1759--67), which devotes several pages to describing Uncle Toby's horror of killing a fly. The literature of Romanticism adopted many elements of the novel of sensibility, but including responsiveness to nature and belief in the wisdom of the heart and in the power of sympathy. it did not, however, assimilate the novel of sensibility's characteristic optimism.

"sentimental novel." Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature. Literary Reference Center. Web. 17 October 2010

Questions to mull over as you interpret the story

Day 1

Background: check with students

Flaubert’s life

- Family class/life: FATHER WAS A SURGEON

- Childhood

- Education

- Travels

- Works

- Aesthetic beliefs OBJECTIVITY

- Reception of Madame Bovary: was it popular? What did critics think of it?

19th century French culture

- Religious attitudes in the time period: FADING -- power of church is weakening

- Sexual attitudes: BOTH PURITANICAL AND OPEN

- Class attitudes (bourgeoisie) -- Economics. Class barriers were fading

- City/rural

- Politics

- Role of reading/literature

19th century European aesthetics

- Realism Concentrate, not on grandly romantic heros (who make deals with devils), or people on epic quests, but on common, everyday people -- the drama of real-life. Objective -- not casting moral judgements.

- Naturalism: a degree of realism with a deterministic slant -- man, as an animal, a product of his environment and experiences. God is nowhere to be seen.

- Art scene -- painters, sculptors, schools of art

- Other Writers -- their similarities to or differences from Flaubert

Based on a true story Eugene Delamare and his wife

Style

- What is meant by "objective" or "impersonal" style?

- Often works by contrasts:

- see 1108 I, v -- Charles and Emma’s view of their marriage

- 1112 I, vii "Charles’ conversation" v. what a man should be, according to Emma

- 1124 -- Charles love and Emma -- "What a booby" I, ix

- These contrasts are usually ironic

- ****Don’t tell students the page number -- 1117 I,viii : read description of old man who had lead a romantic life. Now how would you react to such a person? Then read Emma’s reaction

- Foreshadowing

- 1107 I, v "the other bride’s bouqet! She stared at it. Charles noticed, picked it up, and took it to the attic; [. . . Emma] wonder[ed] what would be done with it if she were to die" how does this section end?

Theme

Essentially, the book is a critique of society. As Flaubert remarked in a letter to his lover Louise Colet, "it is essentially a work of criticism, or rather of anatomy" (NCE 308)

- Exhibit A: the wedding cake: 1104 I, iv

- EXPLAIN bourgeois

- WHAT DOES THIS QUOTE ILLUSTRATE: "Having thus failed to produce the slightest spark of love in herself, and since she was incapable of understanding what she didn’t experience, or of recognizing anything that wasn’t expressed in conventional terms, she reached the conclusion that Charles’s desire for her was nothing very extraordinary" (1114 I, vii)

- MATERIALISM:

- 1122 I, ix -- what she wants from Paris;

- "In her longing she made no difference betten the pleasures of luxury and the joys of the heart, between elegant living and sensitive feeling. Didn’t love, like Indian plants require rich soils, special temperatures? Sighs in the moonlight, long embraces, hands . . ." (1123 I,ix)

Charles

- Exhibit B: Dictionary of the Medical Sciences 1106 I, v. Show how they used to make books with the folded pages.

- Does he actually propose? (1102)

Emma

Small details sketch out her character

- "forehead pressed against the windowpane, looking out at the garden" (1097 I,ii) why in this pose? What does it suggest about her character? (SEE 1119 Ball and peasants I,viii; 887, 921, FOR A LATER MANIFESTATION OF THIS)

- Incipient romanticism

- "Emma herself would have liked to be married at midnight, by torchlight" (1102 I, iii) : what does this illustrate about her character?

- Read 1109-1110 I, 6 and then ask: what would this kind of reading do to a person’s thinking? How would they view love? How would they view life? Who is this reminicist of that we’ve read? (cf. Rousseau 666 Bk 1)******

- "her temperament was more sentimental than artistic, and what she was looking for was emotions, not scenery" (1109 I, vi); her imagination on the cigar case 1122 I,ix;

- At the end of the first chapter, why does the narrator note "she no longer hid her scorn for anything or anyone; and she was beginning now and then to express peculiar opinions, condemning what everyone else approved and approving things that were perverse or immoral" (1127 I, ix).

The scenes

Part One

The school

Roualt’s farm

Emma as a girl/convent

The marriage

The home and realization

The ball

Day 2

Part Two

I Yonville, Houmais, Arrival of Hirondelle

II Dinner and Leon

III Emma bored and with child. Goes with Leon to visit wetnurse (905+ - great scene)

IV Sunday’s with Houmais -- increasing intimacy with Leon

V trip to flax mill: Emma realizes Leon’s in love with him: meeting with Lheureux; plays the good wife

VI Emma in Church -- Abbe Bournisien -- Berthe hurt

VII Leon leaves Rodolphe appears

VIII The fair

XI horse ride

X rendevous with Rodolphe

XI operation on Hippolyte

XII plans to Elope

XIII plans dashed -- convalesence

XIV Lheureux -- comes for the money—Emma finds religion -- and loses it.

XV Opera and meets Leon again

Romantic Love/Romanticism

- Top of 1148: end of II, iv. How does Emma view love?

- READING 1137 II,ii "Nowadays I’m crazy about a different kind of thing -- stories full of suspence, stories that frighten you. I hate to read about low-class heroes and their down-to-earth concerns, the sort of thing the real world’s full of" "You’re quite right" the clerk approved. "Writing like that doesn’t move you: it seems to me to miss the whole true aim of art. Noble characters and pure affections and happy scenes are very comforting things. They’re a refuge from life’s disillusionments As for me, they’re my only means of relief, living here as I do, cut off from the world. Yonville has so little to offer!"

- After her "I have a lover" (1185 II, ix) comment, where does her mind go? BOOKS

- "Her resolution not to be taken in by the display . . ." (1223 II, xv towards the end) How does this line capture Emma’s character?

- On her child, Berthe "she accompanied her caresses with gushings that would have reminded anyone except the Yonvillians of Esmeralda’s mother in Notre-Dame de Paris" (913).

- "She’d be sweet! -- But -- how would I get rid of her later?" (1106 II, Vii)

- romanticism in full bloom: "Have you got your pistols?" (1190 II, x 952)

Materialism continues

- What prevents Emma from fully enjoying her pregnancy and baby (1140 II,iii)?

- Page 1182 (II, ix): what’s another use of materialism? RIDING HABIT

Emma

- What does this line reveal about Emma’s temperament? "her detachment from everything had become so complete, her language was so sweet and the look in her eye so haughty, her behavior was so mercurial, that there was no longer any way of telling where selfishness and corruption ended and charity and virtue began" (1218 II, xiv)

- Windowpane again: 1159 (II,vi)

- Why include her thoughts after her father’s letter? (1191 II, x) How does it effect our understanding of her character?

Religion

- See conversation with the Abbe: 1155 (II, vi) : what does this show about religion and what does it reveal about Emma?

Symbolism

- What are the stallions and bull doing at the agriculture fair? 1170 (II, viii)

- What is Rodolphe sitting under when he writes his "Dear Jane" letter? (1209 II, xiii)

Bourgeois values

- What’s odd about the intelligence valued by the councilor at the agriculture fair (1174, II, viii)? Any of this today?

- Why have the old servant get the medal (1178 II, viii)

- What purpose does Houmais serve? Note that he’s a writer for newspapers (1180 end of II, viii)

Day 3

Book three

I Leon and Emma together again -- coach ride 998

II Father in law dies -- Lheureux needles his way in again.

III interlude with Leon -- gets power of attorney

IV More interludes with Leon -- piano lessons

V Money, Emma falls deeper into depravity

VI Lheruex goes for broke: the notice

VII Frantic for money: Leon, G. -- even Binet

VIII Rodolphe and suicide (1041 takes poison); final appearance of Blind man -- her death 1048

IX the wait over the body -- comedy

X Roualt arrives: the funeral

Why does Emma kill herself? III,vii 1273

Books again:

- (III,ii 1239) Justin’s Conjugal Love: ironic that in a book that was accused of so much scandal, he includes other books.

- (III,v 1248) "She was the amoureuse of all the novels"

Foreshadowing

- (III, ii 1238) Justin and arsenic

- (III,iii 1244) Why add note of Rodolphe in the middle of Leon’s and Emma’s "Honeymoon"?

Church

- (III,I 1233) "The church was like a gigantic boudoir";

- On her deathbed "The priest stood up and tok the crucifix; she stretched out her head like someone thirsting; and pressing her lips to the body of the God-Man, she imprinted on it, with every ounce of her failing strength, the most passionate love-kiss she hadever given" (III,viii 1285)

- At end of novel: the scene b/t Homais and the Abbe

Materialism

- Class: on riding in a cab with an unmarried man "’Everbody does it in Paris!’ It was an irresistible and clinching argument" (III,I,1235)

Money

- "I worship freedom; I abhor restraint, trouble, dependence. As long as the money in my purse lasts, it assures my indpendence [. . . .] The money which a man possesses is the instrument of freedom" (431)<<ROUSSEAU

- She returns to Rodolphe for money: III,viii 1277: "If he had it hw would probably have given it to her . . ."

- III,vii 1268: what does Emma’s frantic suggestions to Leon about getting money suggest?

- **** "Madness began to take hold of her; whe was frightened, but managed to control herself -- without, however, emerging from her confusion, for the cause of her horrible state -- the question of money -- had faded from her mind. It was only her love that was making her suffer" (III,viii 1278) IS THIS TRUE? IF SHE HAD MONEY, WOULD SHE BE SUFFERING? Consider the following quote from Rousseau’s Confessions

- "He waxed his mustache, and signed -- just as she had -- more promissory notes. She was corrupting him from beyond the grave" (III, 11 1296)

Love

- Asleep -- like Rodolphe -- on the night of her funeral

Bourgeois

- Leon as avoiding his fate: "There isn’t a bourgeois alive who in the ferment of his youth, if only for a day or for a minute, hasn’t thought himself capable of boundless passions and noble exploits" (III,vi 1264)

Houmais

- He blurts out news of Charles’ fathers’s death due to anger. III,ii 1239

- What does the satiric rise of Houmais at the end of the novel (the triumph of mediocrity) -- significantly, after Emma’s death -- suggest about how we should judge Emma, v. how we should judge Houmais? What’s better, to have imagination or to be utterly lacking?

Language

- Romance novels, lies, articles by Houmais (which lead to an innocent man being locked up (III,xi 1297), speech at agricultural fair, all of the lies by different people: what does this all mean about language?

Style

Irony

- On Leon: "Besides, he was talented. He painted in water colors, could read in the key of G, and when didn’t play cards after dinner he often took up a book." (II,iii 1139) What’s ironic about his passage? What does it show about Yonville? What does it show about Leon? What does it show

- Emma "What a contempitable, lowdown cad!" she says after the Notary propositioned her. Yet how is this ironic?

- Houmais "affected bohemian ways, he even smoked!" (III,xi 1298) How is this ironic?

- Houmais: "He had every reason to be satisfied with his lot" (III,xi, 1299)

Judgement

- Charles: is he, as Rodolphe believes at the end of the novel, "contemptible"? (III, xi 1300)

Group Questions Day 1

- Why does the novel open with Charles? Given the title, why not start with Emma’s childhood first?

- How does Flaubert suggest, just from the first glimpses we get of Emma, that she enjoys sensuality? (quotes from text are needed here, of course)

- How has Emma's reading shaped her thought?

- What does this line reveal about Emma: "She longed to travel; she longed to go back and live in the convent. She wanted to die. And she wanted to see Paris" (1124)? What does the narrator seem to think about this?

- Given our list of the "I"s of romanticism discussed last week, find passages in the first part that connect romanticism to Emma. (Imagination, Intuition, [anti]-Industrialism, iconoclasm, Individualism, Innocence).

- Two part question on structure: Why end Part I with a ball? Why end Part I with her pregnancy?

- Question on imagery: pay close attention to the wording of the penultimate paragraph of I, ix (1128): what is Flaubert conveying? Work on the ramifications of particular words.

- It's easy (okay, very easy) to criticize Emma. But aren't some of her criticisms of life valid? Let's give two cheers for Emma and find some ways that suggest she a character that, in some way, we could "root" for.

- Given our list of the "I"s of romanticism discussed last week, find passages in the novel that connect to Leon and Rodolphe to specific categories.

- Bovary's humor often comes from bitter irony. This irony is partly revealed in contrasting paragraphs. Look on the following pages for ironies that are revealed through contrasts: 1206 II,xii; 1199 II, xi. What's the irony? How is it bitter?

- What does the description of Yonville (1129-1130 II,i) suggest about its character? Use specific quotes to show this.

- Look closely at the description of Emma's religious piety at the bottom of 1216 and the top of 1217 and 1218 (II, xiv). What do they reveal about Emma's attraction to religion?

- In a letter to Louise Colet, Flaubert writes "the book is a biography rather than a fully developed story. It is not essentially dramatic; and if the dramatic element is well submerged in the general tone of the book the lack of proportion in the development of the various parts may pass unnoticed. But then isn’t life a little like this? An act of coition lasts a minute, and it has been anticipated for months on end. Our passions are like volcanoes; they are continually rumbling, but they erupt only from time to time" (NCE 306). Is this true so far? Is the book more like a biography than a story? How does it still function as a story? How does it not?

Group Questions Day 3

- The biggie: is Emma a character to be scorned, or a character to be sympathized? Arguments for both with examples from the text to support your points.

- The Blind man of the third section of the novel definitely grabs our (and Emma’s) attention -- but what is he doing in a novel of adultery? When does he come into the novel? Why? Why blind? Why so infested with disease?

- How is the following revealed in the novel?

To the entire generation rearered on Romanticism -- and Flaubert is as much a ‘victim’ as Emma -- adultery, because of its officially immoral and asocial status, acquired a symbolic value: it was a sign of unconventionality, rebellion and authenticity. But more important still [. . . ] adultery holds out the promise of beauty precisely because it is the forbidden happiness, the inaccessible dream, that which always eludes: the Ideal. (Brombert 82-83)

- As a youth, Flaubert and his friends developed the following maxim: "Hatred of the bourgeois is the beginning of virtue" (qtd. in Steegmuller 38). 1) how is this early belief manifested in the novel; 2) Why would Flaubert consider this to be a virtue?

- Many critics (Stirling Haag for one) argue that Bovary is a work of satire: starting from the very last line and working backwards, what does Flaubert satirize in the novel?

Notes from

Brombert, Victor. The Novels of Flaubert: A Study of Themes and Techniques. Princeton UP, 1966.

"In a letter to George Sand in which he denied himself as novelist the right to hate or love his characters, he proclaimed unequivocally the importance of sympathie, for that was another manner: ‘One never has enough of that’" (Brombert 22)

As a young man, Flauber wrote to Ernest Chevalier "If ever I take an active part in the world, it will be as a thinker and demoralizer. I will only state the truth; but it will be horrible, creuel and naked" (qtd. in Brombert 16)

Brombert notes that the French poet Baudliere "raised Emma to the rank of a superwoman embodying all the qualities of ‘ideal man’: energy, ambition and above all that ‘supreme and tyrannical faculty,’ imagination" (Brombert 88).

"It is not her intellect, but her capacity to dream and to wish to transform the world to fit her dreams, which sets her apart" (Brombert 85)

FUNCTION OF ADULTERY IN THE STORY

For Flaubert "adultery was a magic word. Ever since his adolesnce the notion of adultery was endowed with a poetic and a tragic meaning. His own life-long dream of an adulterous relation with Elisa Schlesinger had much to do, no doubt, with this poetization fo illegitimate love. But there are other reasons, in addition to the obvious autobiographical echoes. To the entire generation rearered on Romanticism -- and Flaubert is as much a ‘victim’ as Emma -- adultery, because of its officially immoral and asocial status, acquired a symbolic value: it was a sign of unconventionality, rebellion and authenticity. But more important still [. . . ] adultery holds out the promise of beauty precisely because it is the forbidden happiness, the inaccessible dream, that which always eludes: the Ideal." (Brombert 82-83)

"The entire value of my book . . . will have been the ability to walk striaght on a hair, suspended between the double abyss of lyricism and vulgarity (which I want to fuse in a a narrative analysis)" (Brombert 79)

"Confusion, whether due to oppressive monotony, moral drowsiness or spiritual anesthesia, is one of the leitmotifs in Madame Bovary." (Brombert 62-63)

Emma is usually at the window -- which signals both repression (i.e. locked in a prison) and freedom (a means of escape and reverie) (57-58)

Steegmuller, Frances. Flaubert and Madame Bovary: A Double Portrait. New York: Viking Press, 1939. Print.

Fear of bad taste engulfs us like a log (a foul December fog that suddenly appears, freezes your guts, stinks, and stings your eyes), and not daring to advance, we stand still. Think how captious we are becoming, how endless our criteria, our principles, our preconceived ideas, our rules. What we lack is daring" (Steegmuller 235)

"What I should like to write is a book about nothing at all, a book which would exist by virtue 3f the mere internal strength of its style, as the earth holds itself unsupported in the air--a book which would have al- most no subject, or in which, at least, the subject would be almost imperceptible, if such a thing is possible. The finest Dooks are those which have the least subject matter; the more closely the expression approximates the thought, the more beautiful the book is. I believe that the future of art lies in this direction." (Steegmuller 290-91)

"I am writing in an entirely different manner. I want my book to contain not a single agitated page. And not a single observation by the author" (Steegmuller 291)

To Louise ""The entire value of my book, if there is any, will consist in having been able to proceed \ straight ahead on a hair suspended over the double abyss of lyricism and vulgarity, the two qualities I want to fuse in a narrative analysis" (Steegmuller 297)

"Delamare, a few years older than Flaubert and Bouilhet, had been an impecunious and mediocre medical student at the Rouen hospital under Dr. Flaubert. He had never passed all his examinations, and like many another young Frenchman of the time who could not afford to continue his medical studies to the end, had contented himself with becoming not [258] a full-fledged doctor, but an officier de santé--an inferior category of licensed medical man then in existence. He had become the local health officer in a country town near Rouen, and after the death of his first wife, a widow older than him- self, he had married a charming young girl of seventeen or eighteen, the daughter of a near-by fanner. She was pretty, liad been educated in a Rouen convent, where she had read romantic novels, and was delighted to escape from her father’s farm until she discovered that marriage with an adoring nonentity and life in a small country town were even more oppressive. She quickly came to despise her husband. Longed for a more vivid life, began to spend too much money )n clothes, disdained her neighbours, took lovers, sank even more deeply into debt, boredom, and nymphomania, and finally poisoned herself. During the nine years of their mar- riage, Delamare had been perfectly blind to his wife’s ex- travagances and infidelities 5 he could not endure life without her and the revelations of her behavior, and he too killed himself. Their child, a little girl, had been taken in by old Madame Delamare, who had always hated her unbalanced daughter-in-law. They lived in poverty in a village near Croisset, and from time to time the old lady paid a visit of respect to the widow of the great man under whom her son had studied, and accepted Madame Flaubert’s gifts.

Such, in brief, was the story of Eugene Delamare’s tragic marriage. Bouilhet, however, recounted it to Flaubert in de- tail. He reminded him of the black-and-yellow striped cur- tains in young Madame Delamare’s parlour, which had first caused her to be thought pretentious and extravagant by her mother-in-law and her neighbours and had been gossiped about all over Normandy j of the way she had instructed her peasant servant to address her in the third person j of her prettiness, her chic, her haughtiness and nervousness, her at-homes Friday afternoons which she herself was the only" (Steegmuller 257-8)

"Even so, Bouilhet insisted, the idea was good--not only good in itself, but good for Flaubert. Delamare was mediocre, his mediocrity was the mediocrity of the bourgeois 5 about the mediocrity of the bourgeois Flaubert always had much to say j he had lampooned it in the Garcon, he had written from Damascus about a Dictionnaire des Idees Regues j why should he not express himself in a novel, which would be more effective than either? And young Madame Delamare was a character with even greater possibilities. Flaubert could show what there was--not only in her, but in the very air ot the times--to lead her to her fate 5 the essence of the tragedy was her disgust with the surroundings in which she found herself, and beyond which she had somehow learned, [261] however futilely, to look 5 it was the infection of romanticisni, and that too was one of Flaubert’s favourite topics" (Steegmuller 260-1)

"But Sunday night, in- variably, Flaubert read him what he had written during the week--sometimes only a page, or two, or three. Questions of style, of content, of treatment were threshed out: it was some time before Bouilhet was satisfied with the sentence rhythms which Flaubert was to employ. Long and oratorical sentences were of course taboo, and while the simplicity of the style of the Breton book remained a model up to a certain point, the poet now thought that Madame Bovary should be written in prose that was more distinguished, more origin- nally beautiful. Together they read over sentences dozens, even hundreds, of times; and then, when each sentence seemed right, they read over the paragraphs into which they were combined. Gradually, out of single sentences that were simple and direct, Flaubert learned how to construct para- graphs and pages that were also simple and solid, but shim- mering and rich as well 3 inversions, shifts of emphasis, variety in sentence length resulted in a style that was more compelling and stronger than the monotony of the romantics. In the end, Bouilhet was delighted by the impact of the re- suit, and so was Flaubert 5 but it soon became clear that this new style was not something which once conquered could thereafter be employed with ease and swift carelessness. Every sentence, every paragrapti, it seemed, would have to be forged painfully, read aloud, and workec? Over ae-ain and again, like lines of verse; the book could advance only at a snail’s pace; it would take years! It was a staggering prospect!" (Steegmuller 284)

"The language itself is a great stumbling-block. My two characters are completely commonplace, but they have to speak in a literary style, and politeness of language takes away so much picturesqueness from any speech! They will talk about literature, about the sea, the mountains, music--all the well- worn poetical subjects. It will be the first time in any book, I think, that the young hero and the young heroine are made mock of, and yet the irony will in no way diminish the pathos but rather intensify it." (Steegmuller 311)

Letter to Hugo "I believe that at the present time a thinker (and what is the artist if not a thinker in every possible sense of the word?) should have neither religion nor fatherland nor even any so- cial conviction. Absolute skepticism seems to me now so clearly indicated that to want to formulate it would be al- most an absurdity." (Steegmuller 324)

On Hugo and in Praise of Napoleon: "Passion is the ruin of us all." (Steegmuller)

"In art, too, he was a "furious aristocrat": "The task of modem criticism is to restore art to its pedestal. The beauty- f ul cannot be popularized--?m done with antiquity in desiring to render it accessible to chil- dren? Something profoundly stupid. But it is so convenient ‘ for everyone to use expurgated versions of the classics, re- sumes, translations! It is so pleasant for dwarfs to be able to- contemplate truncated giants! What is best in art will always! Elude mediocre natures, that is to say, seven-eighths of thej human race. So why denature truth for the benefit of the[ vulgar?" His work on Madame Bovary gave him visions, vivid and confused, of the art of the future: "I am turning toward a ? kind of aesthetic mysticism. . . . When there is no encouragement to be derived from one’s fellows, when the exterior world is disgusting, enervating, corruptive, and brutalizing, honest and sensitive people are forced to seek somewhere I within themselves a more suitable place to live. If society con-1 tinues on its present path I believe we shall see the return of such mystics as have existed in all the dark ages of the world. The soul, unable to overflow, will be concentrated in itself. The time is not far off when we shall see the return of worldsicknesses--beliefs in the Last Day, expectation of a Messiah, etc. But all this enthusiasm will be ignorant of its own nature,and, the age being what it is, can have no theological f ounda- tion: what will be its basis? Some will seek it in the flesh. Others in the ancient religions, others in art; humanity, like the Jewish tribes in the desert, will adore all kinds of idols" (Steegmuller 326-27)

To Louise ". I like a touch of bitterness in everything--always a jeer in the midst of our triumphs, a dash of desolation even in moments of enthusiasm. That reminds me of Jaffa, where as we approached the town I smelled at the same moment the odour of lemon-trees nd that of corpses? Half-crumbled skeletons lay about in the caved-in cemetery, while over our heads golden fruit hung from green branches. Don’t you feel the consummate poetry of this, that it is the grandest possible synthesis?" (Steegmueller 334)

"It kept going at its usual rate--four days for a page, thirty-nine pages in three months, one himdred and fourteen pages in ten months, three-hour discussions with j Bouilhet over individual scenes" (Steegmueller 341)

"Homais was Flaubert’s final crystallization of the Garcon, of the sententious and absurd bourgeois with a little learning and a head full of idees recues? And he painted him as "at once comic and disgusting. Essentially and personally fetid." (Steegmueller 350)

"in the letter to Achille before the trial, he realized that in many respects he was himself a bourgeois. ‘Be regular and ordinary in your life, like a bourgeois," he once gave as a rule for artists, ‘so that you can be violent and original in your works’" (Steegmueller 409)

"I took a walk in Rouen this afternoon," he wrote to Caroline in 1872, "and met three or four Rouennais. The sight of their vulgarity and of their very hats and overcoats. The things they said and the sound of their voices made me feel like vomiting and weeping all at once. Never since I have been in this world have I felt so suffocated by a disgust for mankind! I kept thinking of Gautier’s love of art, and I felt that I was sinking into a swamp of filth--for Gautier died, I am convinced, of a prolonged suffocation caused by the stu- pidity of the modern age." And the Rouennais were never very proud of Flaubert. "Gustave Flaubert? Nothing but an eccentric," a respectable Rouen business man once replied whien asked his opinion. "Une day he’s living quietly at Crois- set, and the next day he packs his trunk and is off to Carthage! We don’t like that sort of thing very much, in Rouen." (Steegmueller 409-09)

French fashion from the period

Visiting Toilette and Ball Dress

Hand-coloured plate from Graham's Magazine, 1847

Ball Dress

Hand-coloured plate from Graham's Magazine, 1850

Images above from http://marquise.de/en/index.html

Is Emma that much different from housewives of today? This is from a modern romance novel.

Hippolyte

Achille Lemot’s 1869 cartoon with Flaubert dissecting Emma's corpose.

Links

Look how far we've advanced . . . not.

For Richer or Poorer, to Our Visa Card Limit

Jennifer Bayot. New York Times (Late Edition (East Coast)). New York, N.Y.: Jul 13, 2003. p. 1.1

© 2010 David Bordelon