Lesson

Plans

Lesson Plans

Course Documents Links

Home Page

Quick

Links

Library

Links

Citing

Sources

English Romantic Poetry

General

Questions | Group Questions

| Criticism | Pictures | Links

Country/Date

Written/Published

English - 18th century

India - 19th Century

Terms to know

Ode: An elaborately formal lyric poem, often in the form of a lengthy ceremonious address to a person or abstract entity, always serious and elevated in tone. There are two different classical models: in Greek, the epinicion or choral ode of Pindar devoted to public praise of athletes (5th century BCE), and Horace's more privately reflective odes in Latin ( c.23 – 13 BCE ). Pindar composed his odes for performance by a chorus , using lines of varying length in a complex three-part structure of strophe , antistrophe , and epode corresponding to the chorus's dancing movements (see pindaric ), whereas Horace wrote literary odes in regular stanzas . Close English imitations of Pindar, such as Thomas Gray's ‘The Progress of Poesy’ ( 1754 ), are rare, but a looser irregular ode with varying lengths of strophes was introduced by Abraham Cowley's ‘Pindarique Odes’ ( 1656 ) and followed by John Dryden , William Collins , William Wordsworth (in ‘Ode: Intimations of Immortality’ ( 1807 )), and S. T. Coleridge , among others; this irregular form of ode is sometimes called the Cowleyan ode. Odes in which the same form of stanza is repeated regularly (see homostrophic ) are called Horatian odes: in English, these include the celebrated odes of John Keats , notably ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ and ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ (both 1820 ). Adjective: odic. For a fuller account, consult Carol Maddison , Apollo and the Nine: A History of the Ode ( 1960 ).

"ode." The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Ed. Chris Baldick. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Web. 6 October 2010.

Romanticism: A sweeping but

indispensable modern term applied to the profound shift in Western

attitudes to art and human creativity that dominated much of European

culture in the first half of the 19th century, and that has shaped most

subsequent developments in literature—even those reacting against it.

In its most coherent early form, as it emerged in the 1790s in Germany

and Britain, and in the 1820s in France and elsewhere, it is known as

the Romantic Movement or Romantic

Revival. Its chief emphasis was upon freedom of individual

self‐expression: sincerity, spontaneity, and originality became the new

standards in literature, replacing the decorous imitation of classical

models favoured by 18th‐century neoclassicism

. Rejecting the ordered rationality of the Enlightenment

as mechanical, impersonal, and artificial, the Romantics

turned to the emotional directness of personal experience and to the

boundlessness of individual imagination and aspiration. Increasingly

independent of the declining system of aristocratic patronage, they saw

themselves as free spirits expressing their own imaginative truths;

several found admirers ready to hero‐worship the artist as a genius or

prophet. The restrained balance valued in 18th‐century culture was

abandoned in favour of emotional intensity, often taken to extremes of

rapture, nostalgia (for childhood or the past), horror, melancholy, or

sentimentality. Some—but not all—Romantic writers cultivated the appeal

of the exotic, the bizarre, or the macabre; almost all showed a new

interest in the irrational realms of dream and delirium or of folk

superstition and legend. The creative imagination occupied the centre

of Romantic views of art, which replaced the ‘mechanical’ rules of

conventional form with an ‘organic’ principle of natural growth and

free development.

The emergence of Romanticism has been attributed to several

developments in late 18th‐century culture (see preromanticism

), including a strong antiquarian interest in ballads

and medieval romances

(from which Romanticism takes its name). The immediate inspiration for

the first self‐declared Romantics—the German group including the

Schlegel brothers and Novalis—was the transcendental philosophy of Kant

and Fichte, which stressed the creative power of the mind and allowed

nature to be seen as a responsive mirror of the soul. This new German

thinking spread via S. T. Coleridge to Britain and via Mme de Staėl to

France, eventually shaping American Transcendentalism

. English Romanticism had emerged independently with William Blake 's

then little‐known anti‐Enlightenment writings of the 1790s and with the

landmark of William Wordsworth 's 1800 Preface to Lyrical

Ballads. In a second wave after the Napoleonic wars,

Romanticism established itself in France and across Europe; by the

1830s the movement extended from Pushkin in Russia to Poe in the USA.

Romanticism drew some of its energies from the associated revolutionary

movements of democracy and nationalism, although the ‘classical’

culture of the French Revolution actually delayed the arrival of French

Romanticism, and a strong element of conservative nostalgia is also

evident in many Romantic writers.

The literary rebellion of Wordsworth in England and Victor Hugo in

France declared an end to the artificiality of older conventions

, breaking up the 18th‐century system of distinct genres

and of poetic

diction . Lyric

poetry underwent a major revival led by Wordsworth , Keats , Shelley ,

Pushkin , Leopardi , Heine , and others; narrative

verse took on a new subjective dimension in the work of Wordsworth and

Byron , but the theatre tended towards the sensationalism of melodrama

. In fiction, Hoffmann and Poe pioneered the tale of terror in the wake

of the Gothic

novel , while the historical

novels of Walter Scott , Alessandro Manzoni ,

Victor Hugo , and James Fenimore Cooper combined bold action with

nostalgic sentiment. A new wave of women novelists led by Mary Shelley

, George Sand , and the Brontė sisters broke the imposed restraints of

modesty in works of powerful imaginative force. The astonishing

personality of Byron provided Alfred de Musset, Mikhail Lermontov, and

other admirers throughout Europe with a model of the Romantic poet as

tormented outcast. The growing international cult of Shakespeare also

reflected the Romantic hero‐worship which, in the writings of Thomas

Carlyle and R. W. Emerson , became a ‘heroic’ view of history as the

product of forceful personalities like Napoleon.

Although challenged in the second half of the 19th century by the rise

of realism

and naturalism

, Romanticism has in some ways maintained a constant presence in

Western literature, providing the basis for several schools and

movements from the Pre‐Raphaelites

and Symbolists

to expressionism

and Surrealism

. In a broader sense, the term ‘romantic’ may be applied to works and

authors of other periods, by explicit or implicit comparison with a

‘classical’ standard: thus Shakespeare is more romantic than Moličre or

Ben Jonson , both because he disregards the structural models of Greek

drama and because he exploits freely the supernatural elements of folk

legend; and in a different way, W. B. Yeats and D. H. Lawrence are more

romantic than W. H. Auden and E. M. Forster , because they assert the

absolute primacy of their personal visions, rejecting common norms of

objectivity. For a fuller account, consult Aidan Day , Romanticism

( 1996 ).

http://www.rc.umd.edu

Romantic Circles: extensive scholarly resource based at University of

Maryland.

"Romanticism." The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Ed. Chris Baldick. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Web. 30 September 2010.

Questions to mull over as you interpret the poems

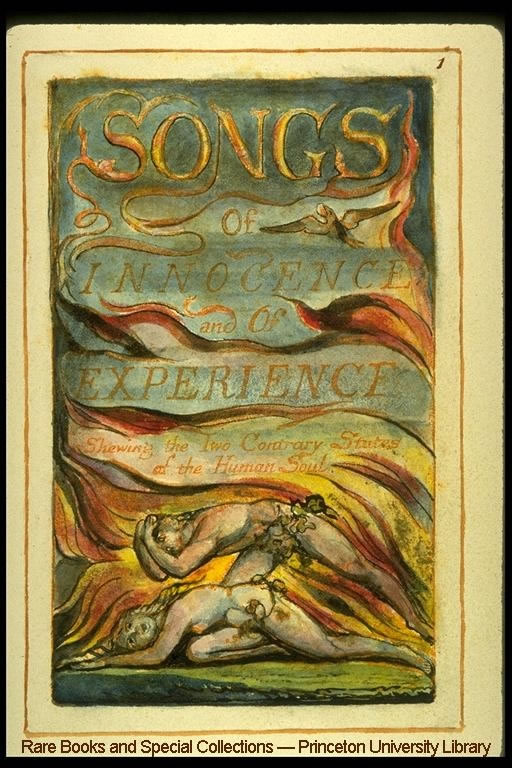

From Songs of Innocence and Songs of

Experience.

Note balance of the title

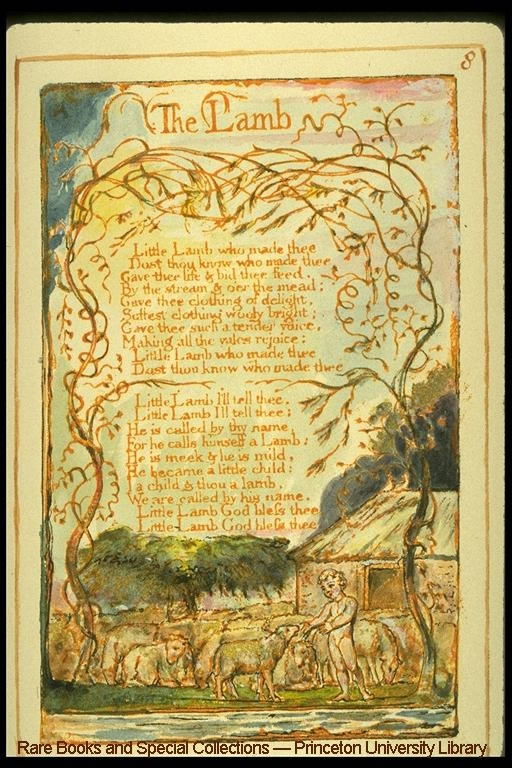

“The Lamb”

- Why a lamb in Songs of Innocence?

- How could the title be figurative? Who/what else could “lamb” refer to?

- How does religious imagery work in this poem

- Which words suggest peace?

- Note the questions – why questions? Why not statements?

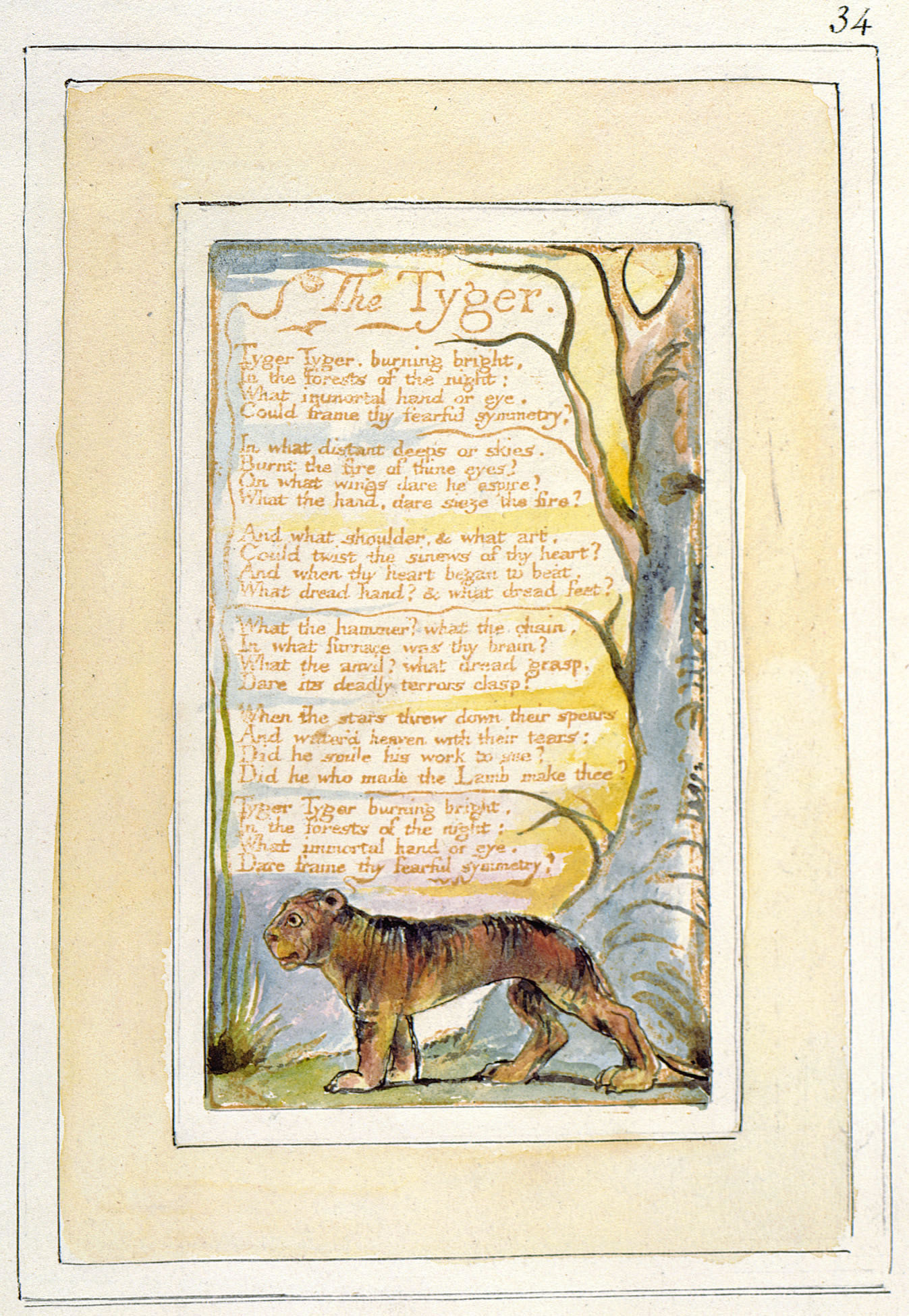

“The Tyger”

- Why a tiger in Songs of Experience?

- Religious imagery again

- Which words suggest danger

- Why the repetition?

- Who’s the “he” refer to?

- Why the subtle change b/t the first and last stanza

- Any reference to industrialization here?

- Lamb could be humans – could Tyger?

- Question marks are very important here. Why so many questions? Who/what are they directed towards?

- Review def. of an ode

- Old poetic form going back to the greeks

- Apostrophe

- Artificial diction

- In original greek, Strophe anti-strophe

- Break down the title: what does Intimations made? How can you have Intimations of Immortality? Is this good thing? Why? When does the poem suggest you have these intimations?

- Written in two parts: 1802 and 1804. Try to find the break.

- Is the poem affirmative or depressive?

Keats "Ode on a Grecian Urn"

- Keats’s life

- Ode again – ask them what it means

- What’s a Grecian Urn?

- Who’s the speaker of the poem speaking to?

- What are some characteristics of the urn, according to the poem? SILENCE, SYLVAN HISTORIAN

- Irony in the poem? IS IT REALLY SILENT?

- Immortality?

- What are the movements in this poem? “Three distinct movements are apparent in these odes: first, the external description of the subject; second, the entering into and becoming one with the subject, creating through imagination an absolute empathy with the experiences suggested; and third, the emergence and separation from the subject, with a commentary about or evaluation of the experience” (Sweetser)

- What is suggested about the power of art at the end of Stanza II?

- In stanza III, who feels the sensation in the last three lines: the characters on the urn? Why or why not?

- And of course, the last lines . . . which have engendered a world or criticism.

- Who’s speaking – and to whom?

- What does truth and beauty mean to the speaker?

- What’s the connection between these lines and the rest of the poem?

- “The meaning of stanza V rests on two antitheses: that which distinguishes the realm of art from the world of human experience, and that which balances the avowal of a radical agnosticism by the affirmation of the consolatory value of art” (Salle)

- “The Ode has shown that to demand absolute truth from art is to crush it under a responsibility which it cannot bear; to regard art as a beautiful semblance of truth is at once to recognize the limitations which it shares with other forms of human knowledge and to re-establish its dignity, though admittedly on a less exalted footing” (Salle)

- “Art is not life but can give meaning to life, provided we remember that it has no meaning apart from life, provided we do not attempt to turn it into some transcendental absolute. Such is the complex reconciliation attempted in the close of the Ode” (Salle)

- “Art, or imaginative activity, cannot lead to absolute knowledge in the world of experience where truth and beauty are distinct; but it can offer to man the consoling image of a world where truth and beauty would be one. The Urn, a product of human art, owes its existence to the attitude of aesthetic detachment which is able to perceive beauty even in the midst of pain” (Salle)

- “But though beauty and art have kept their consolatory function, they no longer provide an answer to the mystery of life. What the Urn expresses is rather the position of the “negative capability” letter: let us accept, since we must, the limitations of human knowledge. One of the ironies of literary fame is that the Ode should so often have been read as a manifesto of unqualified Aestheticism: for it does not say that beauty is the refuge of those who do not think, but the comfort of those whom thought has bruised” (Salle)

Salle, Jean-Claude. "The Pious Frauds of Art: A Reading of The 'Ode on a Grecian Urn,'." Studies in Romanticism 2.2 (Spring 1972): 79-92. Rpt. in Literature Resource Center. Detroit: Gale, 2010. Literature Resource Center. Web. 10 Oct. 2010.

Ghalib

Wordsworth and Keats

- What are some of the intimations of immortality the speaker feels?

- Is "Intimations" an optimistic or pessimistic poem?

- What specific scenes are portrayed on the urn? What do they have in common? What is the speaker's attitude toward them?

- Why is the urn a "Cold Pastoral"?

- Jean-Claude Salle argues that in "Grecian Urn" "Art, or imaginative activity, cannot lead to absolute knowledge in the world of experience where truth and beauty are distinct; but it can offer to man the consoling image of a world where truth and beauty would be one. The Urn, a product of human art, owes its existence to the attitude of aesthetic detachment which is able to perceive beauty even in the midst of pain” (Salle). Is this true?

"Tyger Tyger" from the Blake Archive

"A Grecian Urn"

I always thought Keats meant a vase -- but an urn is an urn -- which means usually a funeral urn: see below.

|

Image Information

|

|

| Title | Cinerary Urn with relief of Actaeon front |

| Date | 2nd C. B.C |

| Material | alabaster |

| Measurements | l. 50, h.73cm |

| Description | from Volterra |

| Repository | Museo Guarnacci |

| Subject | Actaeon (Greek mythology) Artemis (Greek deity) Funerary urns Portraits--Funerary Relief sculpture Sculpture--Etrusco/Italic (Etruria)--199-100 BC effigies |

| ARTstor Collection | ARTstor Slide Gallery |

Tracing of an engraving of the Sosibios vase by Keats

From Wikipedia.

Links

Fine overview of the poem From Brooklyn College "Ode on a Grecian Urn"

© 2010 David Bordelon