Lesson

Plans

Lesson Plans

Course Documents Links

Home Page

Quick

Links

Library

Links

Citing

Sources

The Joys of Motherhood

|

|

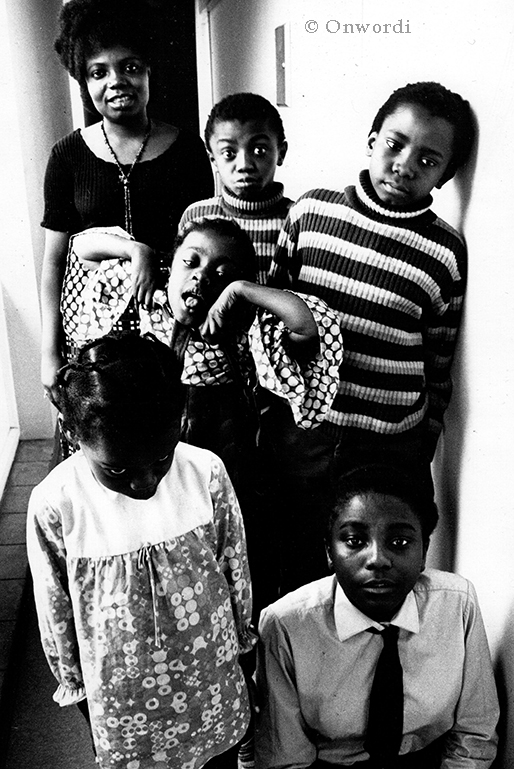

Buci Emecheta and chidlren/ Alone

https://www.buchiemecheta.co.uk/photo-gallery/

General

Questions | Group Questions

| Criticism | Pictures | Links

Language/Country/Date

Published

English/Nigeria/1979

Igbo parents

Terms to know

Feminism

One of the most

important social movements of the past two centuries and certainly the

social movement which has brought about the most enduring and

progressive transformation of human society on a global scale. It is

customary to divide the history of feminism into a First, Second, and

Third Wave, with each period signalling a different era in the struggle

to attain equality between the sexes. Today feminism means many

different things to different people, but at its core, if one goes back

to its origins in the late eighteenth century, it is primarily a social

movement for the emancipation of women. That movement was slow to

start, and it wasn’t until the late 1880s that the term ‘feminism’

actually appeared. Before then, the more usual term was ‘women’s

rights’. The first advocates for women’s rights were for the most part

lonely voices pleading against obvious and manifest iniquities in

society’s treatment of women.

This was certainly the case in one

of the earliest self-consciously feminist works, namely Mary

Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), which was

written at the height of the French Revolution. Establishing what would

become a common theme throughout much feminist writing, Wollstonecraft

conducts her critique on two fronts: on the one hand, she criticizes

patriarchal society (as it would later be called) for the unjust way it

limits women’s rights, as well as their opportunity for education,

self-expression, and economic independence; while on the other hand,

she criticizes women for buying into femininity which, in her view,

turns women into mere ‘spaniels’ and ‘toys’. Wollstonecraft’s solution

was better education for young women, not the granting of equal rights.

So in this sense, one might say feminism begins not with Wollstonecraft

but rather with the various Women’s Suffrage movements that sprang up

in the early 1800s.

Achieving full voting rights for all women

regardless of age, race, or marital status took more than a century of

struggle, easily justifying Juliet Mitchell’s claim that feminism is

‘the longest revolution’. The focus on voting rights, as important as

these are, tends to obscure the fact that it was not only the right to

vote that women were fighting for, though this was of course emblematic

inasmuch that once they could vote they would be able to use the

democratic process to bring about other forms of change. In point of

fact, however, even after women obtained the right to vote in most

parts of the world at the turn of the twentieth century, it was still

several decades before full equality was obtained. And many would say

that it has not yet been obtained.

It is worth mentioning that

throughout the long First Wave of feminism women fought against several

other injustices as well, of which three are key. (i) Women were

restricted in terms of the ownership of property, requiring them to

marry so as to inherit, thus preventing them from attaining true

independence (it is this issue which exercises proto-feminist writers

like Jane Austen and Charlotte Bronte). (ii) Women did not have full

rights over their own body, which meant they had no legal protection

against sexual violence (e.g. the idea that a husband could rape his

wife was not admitted as law until late in the twentieth century).

(iii) Women were discriminated against in the workplace, which not only

meant women were paid less than men for the same work, it also

restricted them from applying for certain jobs, denied them promotion,

and made no allowance for maternity leave. Many of these problems

persist today.

Once suffrage was granted, the women’s rights

movement fell into decline, and remained quiescent until the late 1950s

and early 1960s when it was reignited by a new generation of activists

who called themselves the Second Wave of feminism. Betty Friedan’s The

Feminine Mystique (1963) is generally credited as the tipping point for

this second round of political struggle. Echoing Wollstonecraft, she

argued that women were victims of a false belief in the promise of

femininity and urged them to look beyond their domestic situation for

fulfilment. The National Organization for Women (NOW) was formed in

1966 and became the central focus, in the US, for feminist activism.

Its goal was the ratification of an Equal Rights Amendment to the

Constitution, which it did not manage to achieve in full, but it

nonetheless made giant strides towards it. Second Wave feminism also

took the view that equality between the sexes would only come about if

there was a sea change in cultural attitudes on the part of both women

and men. Authors like Germaine Greer and Kate Millett called for a

sexual liberation as well, arguing that women could alter their status

as the second sex (to borrow the title of Simone de Beauvoir’s

important book) by overturning the double standards applied to their

sexuality and behaviour.

The Second Wave of feminism came to an

end in the early 1980s partly as a result of its successes—many women

felt that all the relevant battles had been fought and won—but

primarily because of the change in political climate. The

Reagan-Thatcher era was very unfriendly to equal rights and it rolled

back many of the gains that had been made. This is the period of the

so-called ‘culture wars’ when feminism was caricatured as mere

political correctness and its political agenda scorned in the press.

Third Wave feminist scholar Susan Faludi documents this in her

Backlash: The Undeclared War Against Women (1991). But there were also

problems within feminism. Feminist scholars of colour, particularly

those from the Third World, argued very forcefully that feminism

neglected race and class. These issues are central to the Third Wave,

which many cite as beginning with the outraged response of feminist

critics to the treatment of Anita Hill during the Senate-confirmation

hearings for US Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas in 1991. Hill

testified that Thomas sexually harassed her when she was working in the

Department of Education, and later at the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission. Thomas flatly denied this, and was subsequently confirmed

by the Senate.

Patriarchy

A

system of social organization where men dominate both the public and

the private spheres. Women are considered secondary and dependent on

men within patriarchal societies, and in consequence lack power,

authority, and resources. Inheritance usually takes place through the

male line, and women may be viewed as men’s possessions rather than as

people in their own right. Many feminists, particularly radical

feminists, regard patriarchy as the source of women’s oppression.

Striving for publicly sanctioned equality has been one measure designed

to eliminate patriarchy.

Patriarchy

A system of social relations that produces inequalities that favour the interests of men over women, or otherwise empower men in general over women. Feminist analysis reveals how this inequitable system is embedded in social, political, and economic institutions, how the domestic sphere is organized, and is reflected in and reproduced through popular discourse and the media. The result is various forms of discrimination and restricted access to power, resources, goods, and services. Patriarchy is expressed spatially with respect to access to public space and workspaces and spatial entrapment in the home.

Castree, Noel, Rob Kitchin, and Alisdair Rogers. "patriarchy." A Dictionary of Human Geography, Oxford Reference, Oxford University Press, 2013. accessed 21 Mar. 2018.

See previous entries on post-colonialism, etc.

Nigeria

History

Excavations

around the Nigerian village of Nok have uncovered some of the oldest

and most beautiful examples of African sculpture. The Nok civilization

flourished between 500 bc and ad 200. In the 11th century the

Kanem-Bornu kingdom extended S from Lake Chad into Nigeria, and the

Hausa established several city-states. In SW Nigeria, the state of

Benin and the Yoruba kingdom of Oyo flourished in the 15th century.

They produced superb brass, bronze and ivory sculptures. The Songhai

Empire dominated N Nigeria in the early 16th century.

The

Portuguese were the first Europeans to reach the Nigerian coast, and

they established trading links with Benin in the late 15th century.

Nigeria became a centre of the slave trade, with major European powers

competing for control. The Igbo established city-states built on the

wealth of the trade. In the early 19th century, the Fulani captured

many of the Hausa city-states. Sokoto retained its independence. The SW

began a protracted civil war. In 1807, Britain renounced the slave

trade, but other countries continued the practice. In 1861 Britain

seized Lagos, ostensibly to stop the trade. By 1885 the British

controlled all of S Nigeria and gradually extended N, conquering all of

Nigeria by 1906. They divided the country into the Colony (Lagos) and

Protectorate of Southern Nigeria and the Protectorate of Northern

Nigeria. The two merged in 1914, and Britain ruled indirectly through

colonial officials and local rulers. Cities, infrastructure and

industries developed. In 1954 Nigeria federated into three regions (n,

E, and W) plus the territory of Lagos.

Politics

Nigeria

became independent in 1960 and a federal republic in 1963. A federal

constitution, dividing the country into regions, was necessary because

Nigeria contains more than 250 ethnic and linguistic groups as well as

several religious ones. Local rivalries have long been a threat to

national unity. In 1967, in an attempt to meet the demands of more

ethnic groups, the country's four regions were replaced by 12 states.

The division of the Eastern Region provoked an uprising. In 1967, the

governor of the Eastern Region, Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu, proclaimed it

an independent republic called Biafra. Civil war continued until

Biafra's surrender in 1970.

In 1998–9 civilian rule was finally

restored. Former military leader Olusegun Obasanjo was elected

president. In the late 1990s and early 2000s riots broke out between

Yorubas and Hausas in the sw, while the introduction of Islamic Sharia

law in northern states has caused friction with Christians. In 2004 the

government claimed that it had put down an uprising in the NE aimed at

creating a Muslim state. In 2006 Nigeria withdrew troops from the

Bakassi peninsula, leading to hopes of an end to a territory dispute

with Cameroon, but in 2007 Nigeria's Senate halted the handover. The

2007 elections were marred by fraud and violence. The ruling party's

candidate Umaru Yar'Adua, a Muslim from the N, became president until

his death in 2010. He was succeeded by Goodluck Jonathan, a Christian

from the S. Jonathan won the presidential elections of 2011. Corruption

remains rife. There is a degree of religious conflict between the

peoples of the mainly Muslim north and the mostly Christian south.

There has been violence in the Niger Delta in protest at the lack of

benefit to the people there of the oil industry. The Muslim militant

group, Boko Haram, is responsible for spates of attacks, chiefly in the

north, including an attack on the UN headquarters in Abuja in August

2011 and multiple bombings in the city of Kano in January 2012.

Continued terrorist attacks by Boko Haram led to a state of emergency

being declared in several northern states in May 2013. Attacks

continued in several states, especially in the NE., as well as the

capital, where a car bomb in April 2014 caused dozens of deaths and

injured hundreds while elsewhere more than 200 girls were kidnapped

from a boarding school. In August Boko Haram declared an Islamic

caliphate in the north-east. The governments of Nigeria and several

neighbours announced that they would set up a force to counter the

Islamist threat. In November, the Nigerian military announced a

ceasefire with the militants and that the schoolgirls would be

released, but both claims were denied by Boko Haram, correctly as it

turned out. Presidential elections due in February 2015 were postponed

until the end of March over security concerns. At the same time the

Nigerian army, somewhat belatedly, launched a serious campaign against

Boko Haram, winning back some territory. In the election Goodluck

Jonathan lost to Muhammadu Buhari of the opposition All Progressives

Congress. Buhari, a Muslim from the north and a retired general, ruled

Nigeria in 1983–5 after a military coup.

Economy

Despite its

many natural resources, including oil reserves, metals, forests and

fertile farmland, Nigeria is a ‘low-income’ developing economy.

Agriculture employs 43% of the workforce and Nigeria is one of the

world's leading producers of cocoa beans, groundnuts, palm oil and

kernels, and natural rubber. Leading food crops include beans, cassava,

maize, millet, plantains, rice, sorghum and yams.

Questions to mull over as you interpret the story

- Start with the "Questions a Feminist critic asks" from our criticism list.

- Let's start with words and their power: what's the difference between jungle v. civilization and urban v. rural?

- What did you learn from the novel? About Nigeria? About relations between peoples there? Economics? Politics? Careers? Education? Gender roles? Living conditions?

- Tensions: rural v. urban; traditional values (Ibuza) v. modern (Lagos); wife v. individual; mother v. individual; capitalism v. ?; free v. slave; outside world v. domestic/native world;

- How are the joys of motherhood ironic? How are they not? If motherhood is so valued, why is Nnu chastised for breast feeding her second wife's child?

- Mental health of Nnu: why open with attempted suicide?

- Role of supernatural in the story?

- Captialism

- Nnu's name means "twenty bags of coweries"

- what are the two faces of capitalism shown on page 51 and 52?

- What do whites stand for in Heart of Darkness? In Things Fall Apart? In The Joys of Motherhood?

- It's widely agreed that Okonkwo is a tragic figure: what about Nnu? How does her life resemble a tragedy?

- What kinds of justice system are they in the novel? Any connection to Things? Consider the courtroom testimony: what does it reveal? What does this trial scene lend to the novel -- in other words, why include it?

- In one family, there's a character who goes to college and graduate school and there's a character who "want[s] to be a hunter" (201). Why?

- Primogeniture: 190, 192

- Language of work: "are your women still on strike?" "The shop steward came to me just by the road there, to say that she is repentant and that she admits she is in the wrong" (143)

- This quote seems to jump out: context is they are taking Nnaife to jail. "We shall always tried to hide your nakedness, Nnaife, and may your chi guide you in this" (211). What do they mean by "nakedness"? Why does it seem more metaphor than literal?

- Older educated children talking to parents: "exaggerated patience" (199)

- Power of words/information:

- consider the following quote - "In those days things were such that Nigerians had no voice. No paper would report what had taken place; even if it were reported, how many of those affected could read, and how many could afford to buy a newspaper?" (148).

- "she and her husband were ill-prepared for a life like this, where only pen and not mouth and really talk. Her children must learn" (179).

- Why open with flashback of Nnu and then go to Ona?

- Why the incident with the buried slave? (23)

- Why set the novel during wartime? What did WWII do to established feminine roles?

- Why the last child (194)?

- At the end of the novel, new seems to lose her mental faculties: "for a while Nnu Ego bore it all without reaction, until her senses started to give way. She became vague, and people pointed out that she had never been strong emotionally" (224).

- And what of her role as a mother God? "Stories afterwards, however, said that Nnu Ego was a wicked woman even in death because, however many people appeal to her to make women per fertile, she never did. Poor Nnu Ego, even in death she had no peace!" (224).

Characters

Nnu Ego

Nnaife

Adaku

Oshiaju

Adimabua

Taiwo

Kehinde

Nnamdio

Ona

Agbadi

Quotes

Women's roles

"God, when will you create a woman who will be fulfilled in herself, a full human being, not anyone’s appendage. … After all, I was born alone, and I shall die alone. What have I gained from this? Yes I have many children, but what do I have to feed them on? On my life. I have to work myself to the bone to look after them, I have to give them my all. And if I am lucky enough to die in peace, I even have to give them my soul. They will worship my dead spirit to provide for them [….] when will I be free?" (186-187)

"when I lost my first son I wanted to die, because I failed to live up to the standard expected of me by the males in my life, my father and my husband – and now I have to include my sons. But who made the law that we should not hope in our daughters? We women subscribe to that law more than anyone. In two we change all this, it is still a man's world, which women will always help to build" (187).

After finding out Adaku plans on sending her children to college, Nnu says "The most important thing is for them to get good husbands" (189).

Narrative irony

'May your Chi be your guide, Adaku,' new ego whispered almost inaudibly as she crawled further into the urine stained mats on heard bug-ridden bed, enjoying the knowledge of her motherhood" (169).

Payroll Officer: "are you not happy you're getting a big sum of sixty pounds, a man's pay for three years? [….] And here you were grumbling that it did not arrive in time. Do you know what lifeblood your husband shed to earn this money? Women! Some of our men or so foolish, giving all that money to an illiterate woman" (179).

See conversation with bus driver at end of novel: "This life is very unfair to men" (223). Physican salaries by gender and race (Fortune By Sy Mukherjee April 11, 2018); White views of discrimination NPR Don Gonyea October 24, 2017.

Traditional Values: 197, 203-04; 204, 193

Question #1

- We've read two novels set in Africa. Let's compare and contrast: for both Things and Joys consider the role of religion, the setting, male and female roles, view of whites, and overall race relations. Add quotes for Joys.

- As long as we're working on comparison and contrast. . . . What about Okonkwo and Nnu? Tragic heroes?

- What is the novel saying about the clash between traditional and modern values (try to settle on a word to describe this)? What does the novel suggest could be the causes of this clash? See pages 179, 210, 213, 218-219

"the

first novel is dedicated to her father; the second to her children; the

third to her mother; the fourth to her friend and publisher, Margaret

Busby; and the fifth to "all mothers" (Chikwenye Okonjo).

Ogunyemi, Chikwenye Okonjo. "Buchi Emecheta: The Shaping of a Self." Contemporary

Literary Criticism, edited by Jeffrey W. Hunter, vol. 128,

Gale, 2000. Literature Resource Center, accessed 15

Apr. 2018. Originally published in Komparatistische Hefte,

vol. 8, 1983, pp. 65-78.

"The novel’s major themes can be quickly summarized as the importance

of motherhood in a West African society, the transformation of gender

and social relations under conditions of colonialism and urbanization,

West African women’s adherence to older religious ideas in the face of

missionization, and significant cultural differences between the

generations born in the colonized, urban milieu of Nigeria and those

raised in rural, largely agricultural villages in the interior"

(Bastian)

"The Igbo word for “dirt” is the same as the term for “pollution” (alu; see Metuh 1985), and Igbo speakers say that alu sticks not only to the person who has performed an abominable act, but to those around him or her." (Bastian).

"It

should not then surprise us to learn that Emecheta’s work has not been

well received in Nigeria, and her books are rarely taught there—unlike

novels by other Igbo writers, most notably Chinua Achebe. This also has

to do with the fact that most of Emecheta’s adult fiction has not been

published by a major Nigerian publisher, making her novels difficult to

find and expensive to purchase. Emecheta herself has taken on the task

of publishing her work in Nigeria but has not yet met with great

success. She is considered too feminist and even too Western by certain

African critics, who point to the fact that she resides permanently in

the United Kingdom and suggest that she has lost touch with Nigerian

values" (Bastian).

Bastian, Misty L. "“Buchi Emecheta’s The Joys of Motherhood”."

Contemporary Literary Criticism, edited by Lawrence J. Trudeau, vol.

397, Gale, 2016. Literature Resource Center,

http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/H1100121659/LitRC?u=toms86543&sid=LitRC&xid=5bc7bc5c.

Accessed 15 Apr. 2018.

First edition cover

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/4/48/Joys_of_motherhood.gif

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/74/Lagos_1929.png

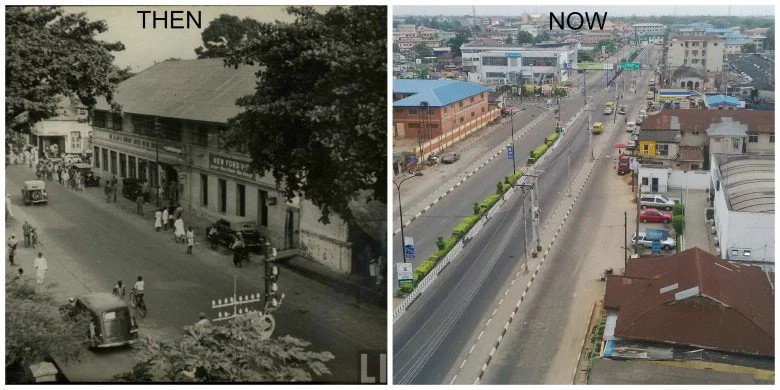

Yaba Largos

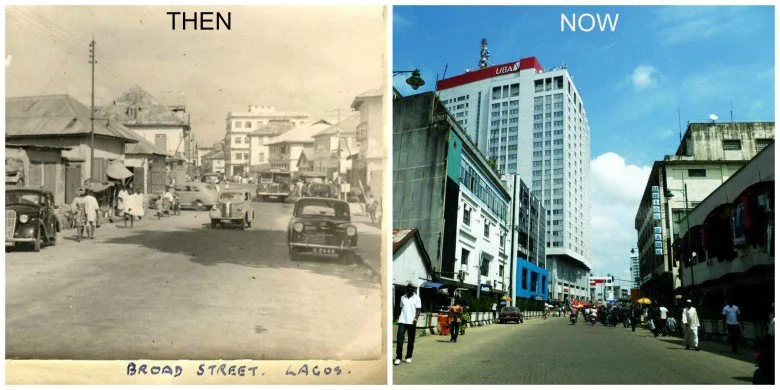

Broad St. Largos

Nigerian Chief and family 1910

http://www.travelstart.com.ng/blog/40-old-photos-that-will-show-you-how-times-have-changed-in-nigeria/

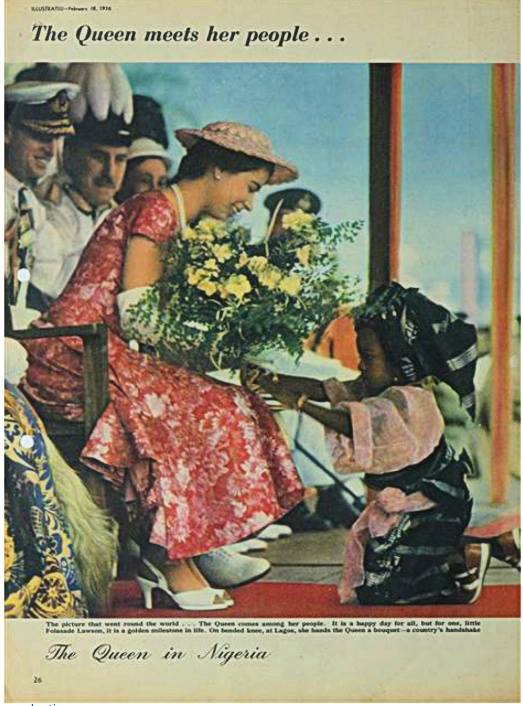

1950s The Queen

1910s Ebute Ero Street Lagos Nigeria by H Hunting of Paterson Zochonis 4546023860 University of Toronto

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1910s_Ebute_Ero_Street_Lagos_Nigeria_by_H_Hunting_of_Paterson_Zochonis_4546023860_University_of_Toronto.jpg

Links

American connection?

Missouri

GOP Senate candidate slams 'feminist she-devils' with 'nasty,

snake-filled heads'. USA

Today, Jan. 26, 2018.

A Teacher Tackles Gender Roles in Her Classroom. WNYC.org, Apr 17, 2018 · by Beenish Ahmed. Then go to page 187.

© 2018 David Bordelon