Transcendentalism: Emerson and Thoreau

|

Back to Lesson

Plan Page

Back to Lesson

Plan Page

Back to Home

Page

Back to Home

Page

Emerson I Thoreau

Terms/People to know

Unitarian: Broadly Christian religion that avoids dogmas and creeds. Popular among New England intellectuals in the 19th century, it was the religion that Emerson first preached in, then left.

Platonism: One of the philosophical tenants Idealism is based on. In Transcendentalism, it provides the philosophical underpinning behind the body/spirit, me/not me dichotomy of Emerson, and the more general desire to, as Thoreau notes, “penetrate the surface of things” (Walden 1858) (and if you see a connection between this last quote and Emerson’s “transparent eyeball,” I’d say you’re being a “creative reader.” Which means you’re on your way to becoming an “American Scholar.”)

To illustrate this connection it's useful to compare it to Plato's "Allegory of the Caves" from Book VII The Republic (a central work of these writers). In this story Plato describes a group of people chained since birth in a cave. They are constrained in movement so they can only see themselves, objects, and others as shadows cast upon a screen. To them, the shadows are "real," because they cannot compare it with anything else. Yet when one of them is released, educated, and returns with the knowledge that shadows are not real, those that have remained deride him and argue that his "eyesight is spoiled" (187). Plato seems to suggest here that reality isn't an extrinsic, constant entity, but a personal mental construction, and as such, is mutable and variable instead of unchanging and static.

Plato. From The Republic. Classics of Western Philosophy. Ed. Steven M. Cahn. Indianapolis, Indiana: Hacket Publishing Company, 1990. 112-190.

Thomas Carlyle: Friend of Emerson and British philosopher and writer. Emerson drew early inspiration from Carlyle's book Sartor Resartus, which espoused a similar philosophy to American Transcendentalism. For a "difficult" writer he was very popular in America, as the quote from a memoirist of the period shows: "Everybody read Sartor Resartus, a crabbed, wise book, with evidence of Carlyle's German browsings on more than one page. Carlyle was a sort of British Thor: when he thundered, people ran out to take a look at the weather" (Reese 197). Excerpts of his books were often reprinted in American newspapers. See below for quotations from Sartor.

Pantheism: worship of nature (with an emphasis on the religious connotation in "worship")

Romanticism: an aesthetic/philosophic approach to art characterized by a freedom from the strictures of realism, an emphasis on the individual and feelings over rationality, and a tendency to look to nature rather than humans or religion for "truth." It seeks to transcend the physical and base itself on an idealized vision of the world.

Brook Farm: one of many utopian communities in 19th century America. Located in West Roxbury Massachusetts and supported by Emerson (Hawthorne briefly lived there and satirized it in his novel The Blithesdale Romance), it represents how seriously many took the reforms (in this case Fourierism) of the day. Similar, in many ways, to the communes of the 1960s (the Oneida Community in upstate New York even advocated a kind of "Free Love"), these communities mark a concrete representation of the romantic ideals sweeping the nation. As Emerson noted in a 1840 letter to Carlyle, "We are all a little mad here with numberless projects of social reform. Not a reading man but has the draft of a new community in his pocket'" (qtd. in Nye Society 54)

The Dial: Transcendental magazine edited by Emerson, Margaret Fuller, and others. Much of Emerson's poetry appeared there.

Emanuel Swedenborg: Swedish theologian (1688-1772) who preached a doctrine on individual and internal living and religion (cf. Emerson's "the Over-Soul") with an emphasis on living a "natural" life. Emerson's thought is much indebted to Swedenborg

Transcendentalism: Great -- now I have to try and define the ineffable . . . . Here goes. A literary/social/aesthetic/quasi-religious movement which stemmed from a belief that God manifested himself in nature. It isn't pantheism because it does not suggest that god is nature, just that god is best exemplified in nature rather than any belief system as exhibited in organized religion. A reactionary movement, it fit in well with the reform minded impulse of the nineteenth-century. While obviously a reaction to the prevailing Calvinist creeds, it shares with it a belief in a dichotomous view of the world: the body/world v. spirit/soul; the imaginary/real. And to reach this "real" world means you have to "transcend" the physical world . . . . which means we have to -- as Emerson, Thoreau, Whitman, Dickinson, et al. suggest -- change our ways.

Abolitionism: The movement to repeal slavery in the U.S. (i.e. to "abolish" slavery).

Fugitive Slave Act: Part of the Compromise of 1850, this federal law made it a crime to assist a runaway slave. This transformed those Northerners who helped run the Underground Railroad into criminals. Both Thoreau and Emerson -- who were abolishinists -- felt that both the Missouri Compromise and the Fugitive Slave law were immoral and wrote against it.

Overview: “Self-Reliance” . Literature and Its Times: Profiles of 300 Notable Literary Works and the Historical Events that Influenced Them . Joyce Moss and George Wilson. Vol. 2: Civil Wars to Frontier Societies (1800-1880s) . Detroit: Gale, 1997. From Literature Resource Center .

Lesson Plan/Teaching Notes

Emerson

Emerson Group Questions

Transcendentalism – general

Where does it come from:

- European romanticism

- Newfound wonder over nature

- Emphasis on self

- Emphasis on emotion over intellect

- Desire to break with tradition

- Reaction to the Great Awakening – movement away from the

harsh religious strictures of neo-puritanism.

It’s important to note that we’re reading only the early

Emerson: See the other essays in the textbook for how his thought developed.

American Transcendentalism is part of the philosophic and

aesthetic reaction to the Enlightenment’s emphasis on reason and rationality.

After several years/decades of strongly emphasizin one aspect of life, what does

a society/culture usually do?

It takes many of its ideas – including an emaphasis on

feelings and nature and as the text book suggests, volcabulary – from the

English Romantic writers Coleridge and Wordsworth, to the European writers

Rousseau, Swedenbourg, Kant and the classic writers Plato and Aristotle. As you

can see, Emerson read very widely.

Transcendentalism has religious roots, but it is not a

religion. It is a more generalized belief that can alter/effect a person’s

religious, moral, and aesthetic outlook.

Fits into the Reform movement as well – Emerson left the

Unitarian church because he couldn’t believe in its doctrine – thus he was the

kind of person who stuck to his beliefs. Reform comes in when he decides to go

public – write and speak – about these beliefs.

Though we only read two main examples, Emerson and Thoreau,

Transcendentalism was a rather crowded field among New England Intellectuals.

One American writer thinker who strongly influenced Emerson was Ellery Channing

. . . . In the same year of the publication of Nature, five other writers

published similar books: George Ripley Discources on the Philosophy of

Religion; Convers Francis, Christianity as a Purely Internal Principle;

Orestes Brownson, New Views of Christianity, Society, and the Church;

Bronson Alcott, Conversaitons with Children on the Gospels; W. H.

Furness, Remarks on the Four Gospels.

His work is aphoristic -- seems composed of pithy sayings. His essays are pieced together from his journals, and later, from his speaking tours.

Thus . . . Reading tip: you have to be “on” for Emerson. his prose does not move by paragraph, but by sentence. Read them slowly and oftentimes, repeatedly, and you'll see his logic. He's discussing metaphysics, which by it's very nature is difficult to put into words.

Emerson 1840: “In all my lectures, I have taught one doctrine, namely, the infinitude of the private man” (qtd. in Matthiessen 6)

Emerson “Historic Notes of Life and Letters in New England” “the mind had become aware of itself. Men grew reflective and intellectual. There was a new consciousness. The former generations acted under the belief that a shining social prosperity was the beatitude of man, and sacrificed uniformly the citizen to the Stated. The modern mind believed that the nation existed for the individual, for the guardianship and education of every man. . . . the individual is the world” (qtd. in Matthiessen 6)

Definitions first:

-

What does Emerson mean by “nature”? Where does he say this?

-

What do you make of the order of chapters? Nature, Commodity, Beauty, Language, Discipline, Idealism, Spirit, Prospects

-

Much emphasis on sight/vision/eyes throughout. Why?

In an 1834 lecture on English literature, Emerson made the following remarks on Coleridge that shed light on his views: “He was of that class of philosophers called Platonists, that is, of the most Universal school; of that class that take the most enlarged and reverent views of man's nature. His eye was fixed upon Man's Reason as the faculty in which the very Godhead manifested itself or the Word was and new made flesh. His reverence for the Divine Reason was truly philosophical & made him regard every man as the most sacred object in the Universe, the Temple of Deity” (qtd in Rusk 239)

Contemporary Views

The United States Magazine, and Democratic Review “call all those together who have feared that the spirit of poetry was dead, to rejoice that such a poem as ‘Nature' is written” (qtd. in Rusk 243)

Thomas Holley Chivers: "Apollo"

"What are stars, but hieroglyphics of God's glory writ in lightning

On the wide-unfolded pages of the azure scroll above?"

Hawthorne "Celestial Railroad"

194 "At the end of the valley, as John Bunyan mentions, is a cavern, where, in his days, dwelt two cruel giants, Pope and Pagan, who had strown the ground about their residentce with the bones of slaughtered pilgrims. These vile old troglodytes are no longer there; but into their deserted cave another terrible giant has thrust himself....He is German by birth, and is called Giant Transcendentalist; but as to his form, his features, his substance, and his nature generally, it is the chief peculiarity of this huge miscreant that nither he for himself, no anybody for him, has ever been able to describe him...."

Break on through to the other side

"The Quarter-Deck"

Ahab: "Hark ye yet again, -- the little lower layer. All visible objects men, are but as pasteboard masks....if man will strike, strike through the mask!....

"The Whiteness of the Whale"

set up as an argument: white is the color of evil, and all the beautiful colors of the world are a trick becasue "all deified Nature absolutely paints like the harlot, whose allurements cover notheing but the charnel-house within." God is dead

Strike through the mask : this suggests that heaven/spirituality is attainable on earth – you don't need to die.

Body/spirit dichotomy

Emerson: Nature

· What tone about the present day [1836] does Emerson set in the first paragraph? Note, in particular, his word choice.

· Who does the “our” refer to on 1107, top paragraph? Who is the “we” as wellWhy include this?

· What is the “not me”?

· What is his definition of Art, and how is it different than the common perception of art?

· What two kinds of beauty does Emerson describe?

· “Nothing divine dies. All good is eternally reproductive” (1113) Would a Puritan believe this? Why or why not?

· Page 1115: what does he mean by “Reason”? How does calling this reason change our understanding of the thing?

· “The corruption of man is followed by the corruption of language” (1116). Is this true?

· What is he suggestiong about nature in the lines “The visible creation is the terminus or the circumference of the invisiible world . . . .” (1118)? Is this positive or negative?

· “The foolish have no range in their scale, but suppose every man is as every other man. What is not good they call the worst, and what is not hateful, they call the best” (1119). What then does he suggest we should do?

· Bottom of 1121 and top 1122 – what is he saying about the nature of all things? EVERYTHING IS CONNECTED

· What does Emerson say about langauge? How does this tie into his view of nature?

· Admits that man is faulty: “Unfortunately, every one of them bears the marks as of some injury; is marred and superficially defective. Nevertheless, far different from the deaf and dumb nature around them” (1122).

· What is idealism?

o LIKE PLATONISM – IDEALISM SUGGESTS THAT THE “REAL WORLD” DOESN'T EXIST AND ONLY OUR MIND EXISTS. EVERYTHING ELSE IS A “PHEOMEMON, NOT A SUBSTANCE” (1129). AND AS HE NOTES “IDEALISM ACQUAINTS US WITH THE TOTAL DISPARAITY BETWEEN THE EVIDENCE OF OUR OWN BEING, AND THE EVIDENCE OF THE WORLD'S BEING” (1129)

· Yet what's the problem with idealism? “IT LEAVES GOD OUT OF ME” (1129)

· What is Emerson saying about evil? IT WILL DISAPPER (CF. 1134)

Religion and Pantheism

· What's his view of nature and religion? How could he be accused of pantheism?

o THEREFORE IS NATURE ALWAYS THE ALLY OF RELIGION . . .PROPHET AND PREIST, DAVID, ISAIAH, JESUS, HAVE DRAWN DEEPLY FROM THIS SOURCE(1120)

o WHAT IS A FARM BUT A MUTE GOSPEL (1121):

o “THE VISIBLE CREATION IS THE TERMINUS OR THE CIRCUMFERENCE OF THE INVISIBLE WORLD” 1118)

o ***“THE ASPECT OF NATURE IS DEVOUT. LIKE THE FIGURE OF JESUS SHE STANDS WITH BENDED HEAD, AND HANDS FOLDED UPON THE BREAST. THE HAPPIEST MAN IS HE WHO LEARNS FROM NATURE THE LESSON OF WORSHIP” (1129)

o “IS NOT THE LANDSCAPE, EVERY GLIMPSE OF WHICH HATH A GRANDEUR, A FACE OF HIM?” (1130)

EMERSON LINKS THIS PANTHEISM TO THE MIND/REASON: AFTER NOTING THAT THE SPIRIT/GOD IS INEFFABLE “WHEN WE TRY TO DEFINE AND DESCRIBE HIMSELF, BOTH LANGUAGE AND THOUGHT DESERT US, AND WE ARE AS HELPLESS AS FOOLS AND SAVAGES” (1129), HE QUALIFIES THIS WITH

o “WHEN MAN HAS WORSHIPPED HIM INTELLECTUALLY, THE NOBLEST MINISTRY OF NATURE IS TO STAND AS THE APPARITION OF GOD” (1129)

Contrast with Puritanism/established religion

· Denies total depravity “The ruin or the blank, that we see when we look at nature, is in our own eye” (1133)

Art

· what helps us develop idealism? POETRY 1124

Spirit/metaphysics

· Emerson notes that “behind nature, throughout natuer, spirit is present; that spirit is one and not compound . . . .” (1129). What does this suggest about his thinking of nature/spirit? Is it positive or negative? What makes you think so? Cf. Melville

· Emerson lists a series of what he calls “occasional examples of the action of man upon nature with his entire force” (1133). His list includes a mix of both the metaphysical (“the miracles of enthusasim”) and the concrete (“the abolition of the Slave-trade” [1133]).

Reason/intellect

- In the chapter “Prospects,” Emerson sets up a dichotomy of “Empirical science” v. “manly contemplation” (1130). Disregarding the gender bias, what's the difference/distinction b/t these two for Emerson? Which is better and why?

- While earlier he asked for unity, now he seems upset by unity: now he calls it a “tyrannizing unity” (1130). But he stills wants a kind of unity – though now it's a unity that can see the “metaphysics of conchology, of botany, of the arts, . . . .” (1131) cf. 1121 for similar conception of unity

In “Prospects” he makes several observations:

· “'The foundations of man are not in matter, but in spirit” (1132)

· “We distrust and deny inwardly our sympathy with nature” (1132)

· “A man is a god in ruins. When men are innocent, life shall be longer, and shall pass into the immortal, as gently as we awake from dreams” (1132) cf. Bartlett and Horace Mann

· “Man is the dwarf of himself” (1132)

Culture/current events

· Why ask “What is a woman” in “Prospects”?

Second group of notes

Organization

Chapters: Nature, Commodity (1109), Beauty 3 PARTS (1110), Language 3 PARTS (1114), Discipline (1118), Idealism (1122), Spirit (1128), Prospects (1130)

Organization/compensation

· Why group 1109 these things together – how are they related? How do they contrast

For Emerson, what is technology connected to? 1110 cf. 1107

What's the point of commodity? SATISFY SENSES

Does his first observation on beauty hold true? 1111

Kinds of beauty: What's the difference b/t 1) BODY and 2) SOUL/SPIRIT

1116 is this still true?

What does discipline mean? 1118

If all is order, where does evil fit in? 1121

Tension b/t senses and reason (1123)

“emancipate” what does this suggest about nature's hold on us? What kind of nature is this? 1124

What does a poet do? 1124

How is E's connection b/t “religion and ethics” similar to Franklin's? 1127

What distinction does he make b/t idealism and religion? Ho is this similar to Franklin? 1128

How is this a problem of Transcendentalism 1129.

Emerson: Poetry and "American Scholar"

- What's the emphasis on Rhodora? How is nature characterized?

- Why a Rhodora and not a rose?

· Without looking at the book, complete this sentence from “The American Scholar” “The first in time and the first in importance of the influences upon the mind is that of _____” (1136) NATURE

· “He shall see that nature is the opposite of the soul, answering to it part for part. One is seal, and one is print. Its beauty is the beauty of his own mind” (1137)

· “Each age, it is found, must write its own books; or rather, each generation for the next succeeding” (1137). Then why are we reading his books?

· According to Emerson, are books bad? NOT BOOKS, PER SE, BUT WHAT THEY CAN DO TO THE REASON “THE GUIDE IS A TYRANT” (1137) B/C IT KEEPS REASON AT BAY. What does he warn against? “BOOKS ARE WRITTEN ON IT BY THINKERS, NOT BY MAN THINKING” (1138)

· “The one thing in the world of value, is, the active soul – the soul, free, sovereign, active” (1138)

· What does he mean by “creative reading” (1139)

· What does Emerson feel is the danger of books? (1137)

· What does Emerson feel is the role of the scholar in society? (1142)

· How is “to defer never to the popular cry” both good and bad? (1142 – cf. quote about “popgun is a popgun” 1143)

· Is his question on “every man a student” (1136) true?

Connections to Romanticism

· Bottom of page 1138

Connections to Nature

· What ideas in “The American Scholar” are similar to ideas in Nature?

· How does “our day of dependence” (1135) connect to nature

· How does “the genius always looks forward . . .” (1138) connect to nature

· “The so called practicl man” (1139) connect to Nature

Attacking anti-intellectualism

· What does he suggest, early on, about the position/role of the intellectual in American culture. “THE LOVE OF LETTERS AMONG A PEOPLE TOO BUSY TO GIVE TO LETTERS ANY MORE” (1135)

Influence of other cultures/nations

· “Our day of dependence . . . to the learning of other lands” (1135) cf. publishing practices which ensured that foreign writers were cheaper

“Brahma” (Packet) [published in 1857]

Doctrine of compensation

Why “red”?

from http://www.lehigh.edu/~ejg1/teach/logan2.html

Emerson, "The American Scholar"

1. What is the nature of the American scholar? What authorizes him as "learned"?

2. What is the relationship of the scholar to society? Emerson to his own audience?

3. To what degree does Emerson seem aware of himself as constructing a new national literature or identity? How do you see this in his text?

Self Reliance

4. What is self-reliance and what is entailed in being self-reliant?

5. What is the relationship between society and the individual?

6. If one is self-reliant, according to Emerson, what happens to one's responsibilities to others?

General questions about Emerson:

7. Who has access to Emerson's ideals? Why?

8. Given Emerson's idealism, it seems curious that his work is littered with metaphors of the body. Locate some of these and think about how they work.

9. Emerson was writing in the context of the Panic of 1837 (comparable in many ways to the Great Depression) and the rise of industrial capitalism. In what sense can one view his work as a response to these events?

0. How does Emerson characterize his age? How does he characterize its relationship to the past?

11. According to Emerson, what is the purpose/realm of art? the artist? What notions of art does he critique?

12. What kind of reader is Emerson? How does he characterize the values and risks of reading? How can one read most usefully?

13. Select some of Emerson's self-confident epigrams: Test, challenge, and examine its seeming simplicity for complexity.

14. How does Emerson provoke his audience? What sense do you have of his readers' resistance?

Group questions on Emerson Part I

1) Using the following definition from the Backgrounds of American Literary Thought, trace out, using examples from Nature, how Emerson exemplifies Transcendental philosophy.

Transcendentalism was

The triumph of feeling and intuition over reason, the exaltation of the individual over society, the impatience at any kind of restraint or bondage to custom, the new and thrilling delight in nature (Horton and Edwards 116)

2) How could Transcendentalism be considered part of the reform movements that were so popular antebellum society? Another way of answering this question is to consider how it promotes reform . . . and what kind of reform is it promoting? Quotes and explanation please.

3) In “The American Scholar” Emerson notes that “One must be an inventor to read well” (1139). Why does he believe this is so? What other ideas in the essay does this reflect? (supply quotes).

4) “A man should learn to detect and watch that gleam of light which flashes across his mind from within, more than the luster of bards and sages” (1160). How does this line, from “Self-Reliance,” connect to “The American Scholar” and Nature? Direct quotes and explanation of connection please.

Group questions on Emerson Part II

- Emerson, in the essay “Compensation,” writes “[. . .] dualism underlies that nature and condition of man Every excess causes a defect; every defect an excess. Every sweet hath its sour; every evil its good”* (139 Norton edition). What does he mean by this “dualism”? Find reflections of this idea in the essay’s of his that we’ve read (you can check 1136, 1162, 1174) as well as other places How is this idea illustrated in his poem “Bhrama”?

- In “Self-Reliance” Emerson warns that “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds” (1164). What does he mean? How does it fit into the idea of trusting your own intellect, which is the overall idea of the essay?

- Why are symbols so important to Emerson? Why do they make poetry? He writes that “We are far from having exhausted the significance of the few symbols we use. We can come to use them yet with a terrible simplicity” (1182). What does he mean by “a terrible simplicity”?

- Emerson writes that “I look in vain for the poet whom I describe” (1189). Let’s help him. What are two qualities of the poet that Emerson is looking for? Of what does this poet need to sing? We’ll keep these in mind as we approach Thoreau, Whitman, and Dickinson.

Thoreau

Group Questions

General

questions

- Does he suggest everyone

should go live in the woods?

- Why a lake? “A lake is

the landscape's most beautiful and expressive feature. It is earth's eye;

looking into which the beholder measures the depth of his own nature.”1905 “It

is perennially young” 1909; links it to himself 1909 an ascetic “hermit” (cf.

1924 as well for reference to hermit)

- ???What is he getting at

with the questions on other planets on 1877?

- ???What kind of “dead

man” is he talking about on 1878?

- Is his voice the same

throughout the book? Does his tone change from beginning to end?

Opening

- Discuss the epigraph:

- What time does it set?

- Why a chanticleer?

- Why wake neighbors

up? Literal or figurative?

- What ode is he

referring to?

- Why a “sojourner” (1808)

- 1808 How does his

emphais on “I” – and avowal of it – effect our reading of the book?

- 1809 “pushing all these

things before them.” How does this scene play into the idea of economy?

- 1810 “It is hard to have

a Southern overseer; it is worse to have a Northern one; but worst of all when

you are the slave-driver of yourself.” What’s odd about this quote? What does

he mean? And note the sentences which follow --

- “Talk of a divinity in

man! Look at the teamster on the highway, wending to market by day or night;

does any divinity stir within him? His highest duty to fodder and water his

horses! What is his destiny to him compared with the shipping interests?

Does not he drive for Squire Make-a-stir? How godlike, how immortal, is he?”

“Former Inhabitants”

- What’s the purpose of

“Former Inhabitants” 1941?

“The Pond in Winter”

- What time is it 1954?

- What is the answer to

question posed in the first paragraph 1954? FORWARD

“Spring”

- Note page 1971 “We

should be blessed if we lived in the present always, and took advantage of

every accident that befell us” – what is he getting at here?

- Is this still true?

“Our village life would stagnate if it were not for the unexplored forests and

meadows which surround it. We need the tonic of wildness” 1973 What does

Thoreau mean by this?

- “At the same time that

we are earnest to explore and learn all things, we require that all things

be mysterious and unexplorable, that land and sea be infinitely wild,

unsurveyed and unfathomed by us because unfathomable. We can never have

enough of nature. We must be refreshed by the sight of inexhaustible vigor,

vast and titanic features, the sea-coast with its wrecks, the wilderness

with its living and its decaying trees, the thunder-cloud, and the rain

which lasts three weeks and produces freshets. We need to witness our own

limits transgressed, and some life pasturing freely where we never wander.

We are cheered when we observe the vulture feeding on the carrion which

disgusts and disheartens us, and deriving health and strength from the

repast.” 1973

“Conclusion”

- What idea is he getting

at here 1976 “I learned this, at least, by my experiment: that if one

advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the

life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common

hours. He will put some things behind, will pass an invisible boundary; new,

universal, and more liberal laws will begin to establish themselves around and

within him; or the old laws be expanded, and interpreted in his favor in a

more liberal sense, and he will live with the license of a higher order of

beings.”

- What is he getting at by

the story of the artist in Kouroo? 1978

- 1980 – why not live in

the world? “I delight to come to my bearings -- not walk in procession with

pomp and parade, in a conspicuous place, but to walk even with the Builder of

the universe, if I may -- not to live in this restless, nervous, bustling,

trivial Nineteenth Century, but stand or sit thoughtfully while it goes by.

What are men celebrating” 1980

- Review last line 1982

Ironic

humor/wit

- I should not talk so

much about myself if there were anybody else whom I knew as well.

Unfortunately, I am confined to this theme by the narrowness of my experience.

1808

- After a discussion of

the fauna of the lake, laconically notes “These are all the animals of

consequence which frequent it now” (1905). What’s odd/ironic about this line?

Spirituality

In a letter a few years

after Walden, he wrote “our souls (I use this word for want of a better)” (qtd.

in Drake 72)

Drake, William. “Walden.”

Thoreau. Cliffwood, NJ: Prentice Hall. 71-91.

Emphasis on spirituality

instead of religion

Contrast the number of

times the word god appears in Nature and in Walden

Romanticism

- Describe the Canadian

wood cutter? 1883 Now why does T. include him? 1884

Being

Alive

- “The amount of it is, if

a man is alive, there is always danger that he may die, though the danger must

be allowed to be less in proportion as he is dead-and-alive to begin with. A

man sits as many risks as he runs.” (Walden 1888) – what is he talking about

here?

Anti-Irish

- 1913, John Field 1914 –

insults all Irish 1915. Why include this incident? See quote on page 1916.

Structure

- When does book open?

Explain significance of date.

- What season does it open

in? What season does it end in?

- At what time of day does

“Sounds” open with 1866? When does it end?“

- What about

“Solitude”1175 - 1880?

- “Ponds”? 1899

- Why move from “solitude”

to “Visitors” 1881

- Note transitions b/t

paragraph

- Why include the “Bean

Field” chapter?

Chapters

Economy 1807; Where I

lived, and What I Lived For 1850; Reading 1860; Sounds 1866; Solitude 1175;

“Visitors” 1881; “The Bean-Field” 1888; “The Village” 1895; “The Ponds” 1898;

“Baker Farm” 1912; “Higher Laws” 1917; Brute Neighbors 1924; House-Warming 1931;

Former Inhabitants and Winter Visitors 1941; Winter Animals 1948; the Pond in

Winter 1954; Spring 1963; Conclusion 1974

Environmental

concerns

- Page 1905 – notes the

loss of trees around the edge of the pond

- 1918 note on how he

stopped shooting birds for specimans

- bison and

nature/cranberries l93l

Connection

to Nature

“ This is a delicious

evening, when the whole body is one sense, and imbibes delight through every

pore. I go and come with a strange liberty in Nature, a part of herself.”

(Walden 1875) cf. Transparent eyeball

- page 1974 – Thoreau

offers his version of compensation – cf. Brahma

Train/industrialization

- What is his view of

trains?

- Leo Marx’s the

machine in the garden – i.e. garden of Eden

- What do you make of his

description of the contents to the train 1871-72?

Style

- what is the tone

throughout the book? Is it elevated? Informal? How can you tell? Find a

passage , 1865 – “Harper” – brand name

- Does this tone change?

Does he seem interested in the same things throughout the book? Would

this entail a change in tone?

- one characteristic of

common speech is proverbs – does Thoreau use/make them?

- Often works with

contrasts: cf. 1895 – colony of muskrats v. colony of humans.

- Let’s take a look at

page 1897. What do you make of his comments on the night – and then the end

of the page? “Every man has to learn the points of compass again as

often as be awakes, whether from sleep or any abstraction. Not till we are

lost, in other words not till we have lost the world, do we begin to find

ourselves, and realize where we are and the infinite extent of our relations.”

(Walden 1897); cf 1956 and 1959-60 on the depth of the pond as a correlative a

man’s thought

- Why the shift in diction

in “Brute Neighbors” 1924 –

- Why the reference to

the Fugitive Slave Bill 1929 to finish up the section on the battle of the

ants?

- Why the long, detailed

descriptions of nature? For instance, see page 1966 – on the sand coming out

of the embankment? How does this fit into the themes of the book?

- “I am affected as if

in a peculiar sense I stood in the laboratory of the Artist who made the

world and me -- had come to where he was still at work, sporting on this

bank, and with excess of energy strewing his fresh designs about. I feel as

if I were nearer to the vitals of the globe, for this sandy overflow is

something such a foliaceous mass as the vitals of the animal body.” 1967

- AND “What is man but a

mass of thawing clay” (1968)

- And “Thus it seemed

that this one hillside illustrated the principle of all the operations of

Nature. The Maker of this earth but patented a leaf. What Champollion will

decipher this hieroglyphic for us, that we may turn over a new leaf at

last? This phenomenon is more exhilarating to me than the luxuriance and

fertility of vineyards. True, it is somewhat excrementitious in its

character, and there is no end to the heaps of liver, lights, and bowels, as

if the globe were turned wrong side outward; but this suggests at least that

Nature has some bowels, and there again is mother of humanity.” (1968)

- BEST ONE – the insect

eating its way out of the table – “a ressurection” 1982

- 1981: how does he soften

the attack?

Important quotes

“How many a man has dated a

new era in his life from the reading of a book! The book exists for us,

perchance, which will explain our miracles and reveal new ones. The at present

unutterable things we may find somewhere uttered. These same questions that

disturb and puzzle and confound us have in their turn occurred to all the wise

men; not one has been omitted; and each has answered them, according to his

ability, by his words and his life.” (Thoreau 1864)

“Moreover, with wisdom we

shall learn liberality.” (Thoreau 1864)

“We need to be provoked, --

goaded like oxen, as we are, into a trot” (Thoreau 1865)

“Alas! what with foddering

the cattle and tending the store, we are kept from school too long, and our

education is sadly neglected.” (Walden 1865)

In response to the question

don’t you get lonely? “This whole earth which we inhabit is but a point in

space. How far apart, think you, dwell the two most distant inhabitants of

yonder star, the breadth of whose disk cannot be appreciated by our instruments?

Why should I feel lonely? is not our planet in the Milky Way? This which you

put seems to me not to be the most important question. What sort of space is

that which separates a man from his fellows and makes him solitary? I have

found that no exertion of the legs can bring two minds much nearer to one

another.” (Walden 1877)

“We meet at meals three

times a day, and give each other a new taste of that old musty cheese that we

are. We have had to agree on a certain set of rules, called etiquette and

politeness, to make this frequent meeting tolerable and that we need not come to

open war.” (Walden 1879)

“A puritan may go to his

brown-bread crust with as gross an appetite as ever an alderman to his turtle.”

1921

“Perhaps these pages are

more particularly addressed to poor students.” (Walden 1808)

Group Questions on Walden Day 1

Remember to list quotes and page numbers for each question

- How does his emphais on “I” – and avowal of it – effect our reading of the book (1808)?

- In the Puritan writers, we often read biblical excerpts. What spiritual guides are quoted here? (1814, 1839, 1837, etc.) What moral or lesson does he derive from them? (cf. 1853, 1854) What does this reveal about Thoreau’s philosophy? (1858)

- In a contemporary review in the National Anti-Slavery Standard, a critic wrote that in Walden “The author mercilessly probes the shallow conventionalism, the shams of the day; he proclaims war to the knife with all snobism. Penetrating to the very pith and core of modern society, he lays bare the worm of corruption which preys upon its vitals – shows hideous rottenness concealed beneath a fair and alluring exterior. Thoreau is Carlisle simplified. The Anglo-German jargon of the latter is translated into pure English” (qtd. in Harding 337).

What is the “shallow conventionalism” that he exposes? What are the “shams of the day”? What is the “worm of corruption” that is preying on society? (these pages might help: 1810, 1812,1855, 1888, 1897)

- List a connection from Walden to Emerson’s Nature, “The American Scholar,” and “Self Reliance” that illustrates the similarities in their philosophies.

- How are Enlightenment values, as expressed by the works of Franklin and Irving, prevalent in our society today? And yes, your mid term should include quotes from the works we’ve read.

Group Questions on Walden Day 2

- Why a pond?

- Why the long, detailed descriptions of nature? For instance, see page 1966-68 – on the sand coming out of the embankment? How does this fit into the themes of the book?

- Thoreau writes that “not till we are completely lost, or turned round -- for a man needs only to be turned round once with his eyes shut in this world to be lost -- do we appreciate the vastness and strangeness of nature. Every man has to learn the points of compass again as often as be awakes, whether from sleep or any abstraction. Not till we are lost, in other words not till we have lost the world, do we begin to find ourselves, and realize where we are and the infinite extent of our relations.” (1897)

What is he getting at here? Why do we have to get “lost” to find ourselves? Does this tie in with other ideas in the text? Where?

- How are Transcendental values, as expressed (or critiqued) in the work of Hawthorne, Emerson and Thoreau prevalent in our society today? And yes, your mid term should include quotes from the works we’ve read.

Voices from the Past

Carlyle's Sartor Resartus (1833-34)

Platonic

43 "This Dreaming...is what we on Earth call Life"

52 "For Matter, were it never so despicable, is Spirit, the manifestation of Spirit....The thing Visible, nay the thing Imagined, the thing in any way conceived as Visible, what is it but a Garment, a Clothing of the higher, celestial Invisible..."

45 "Man is a Spirit...Clothes...are the visible emblems of that fact."

cf. Melville and Emerson: "the Charnel-house of Nature" (45) "All visible things are Emblems" (56), 129 a "Fire-Baptism", 130 the "NOT-ME"

Nature

Teuf. "We speak of the Volume of Nature: and truly a Volume it is, -- whose Author and Writer is God....It is a volume written in celestial hieroglyphs, in the true Sacred-Writing.

Work

71 Man's "vocation is to Work"

126 "A certain inarticulate Self-consciousness dwells dimly in us which only our Works can render articulate and decisively discernible. Our Works are the mirror wherein the spirit first sees its natural lineamanets. Hence, too, the folly of that impossible Precept, Know thyself; till it be translated into this partially possible one, Know what thou canst work at."

The "Everlasting Yea" ends on this exhortation: "`I too coould now say to myslef: Be no longer a Chaos, but a World, or even Worldkin. Produce! Produce! Were it but the pitifullest infintesimal fraction of a Product, produce it in God's name! 'Tis the utmost thou hast in thee; out with it then. Up, up! Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy whole might. Work while it is called To-day, for the Night cometh wherein no man can work." (149)

Barrett, Benjamin Fiske. Beauty for Ashes; or The Old and the New Doctrine, concerning the state of Infants After Death, Contrasted. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1855.

Inscribed "Reverend Henry Ward Beecher with the best regards of the Author Brooklyn Feb. 9, 1856.

"The Old doctrine is a sad one, and consorts only with gloom; while the New doctrine is cheerful, and gladdens the heart with its serene sunshine" (Barrett vi).

The New doctrine is from "Swedenborg" -- a "New Dispensation of Christianity" (Barrett 10).

Godley, John Robert. Letters From America. 2 Vols. London: John Murray, 1844.

British visitor to America

"A strong tendency also exists to prefer German university regulation to ours, that is, mere instruction to instruction joined with moral discipline. . . . The dark side of Germany is the skepticism and rationalism of its literary men; . . . .[97] Here the importation of German rationalism is particularly dangerous, for none of these counteracting principles ["conservative habits of the country. . .submissive religious feelings of the more ignorant classes]; and the spread of Unitarianism, Rationalism, and Pantheism, by which New-England is now overrun, appears very alarming." (Godley 97)

In a footnote, he comments: "To see a God in every star, to people every wood and stream with guardian spirits, is infinitely better than to recognize the existence of neither God nor spirit any where' for in fact it comes to that, those who call themselves Pantheists being, in nine cases out of ten, practically Atheists. Perhaps extremes meet in this case, so that the prevalence of Pantheistic doctrines among the educated classes may be connected with, and lead to, superstition and idolatry among the vulgar." (158)

In a footnote, he comments: "To see a God in every star, to people every wood and stream with guardian spirits, is infinitely better than to recognize the existence of neither God nor spirit any where' for in fact it comes to that, those who call themselves Pantheists being, in nine cases out of ten, practically Atheists. Perhaps extremes meet in this case, so that the prevalence of Pantheistic doctrines among the educated classes may be connected with, and lead to, superstition and idolatry among the vulgar." (158)

The New World. "Transcendentalism" August 8, 1840 (157) rev. of the debut of The Dial

Popular "mammoth" newspaper of the antebellum period.

- "As the question is often put to us, what is transcendentalism, we can best convey an answer by quoting the following very luminous and clear definition from what Mr. Alcott modestly calls his `Orphic Sayings'. (157)

- `The popular genesis is historical. It is written to sense not to the soul. Two principles, diverse and alien, interchange the Godhead and sway the world by turns. God is dual. Spirit is derivative. Identity halts in diversity. unity is actual merely. The poles of things are not integrated [etc.]

- From this it is clear as mud what transcendentalism is. Or readers can not fail to be enlightened by so simple an explanation. Seriously: from the tenor of nearly every article in The Dial we infer, that the transcendentalist believe "that each individual soul is a finite portion of, and an emanation from, the infinite spirit . . . "

- It is not difficult to see that this is merely a refined sort of Deism, and that it strikes at once at the vital principal of the faith of Christianity." (157)

- "The commonest tyro in philosophical history will see the absurdity of the claims of these people to novelty and originality. Their philosophy is merely Platonism revived. Their doctrine, with regard to the soul, is precisely that which was taught by Zeno of Cyprus." (157)

Talcott, Hannah Elizabeth Goodwin. Dr. Howell's Family. Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1869.

This novels shows that not all were enamored with Transcendentalism (see also Alcott's "Transcendental Wild Oats" in our textbook)

Stephen confides to a Captain Ashmead about worries about infecting his sister with the metaphisics he learned in college: "I've given Di a world of anxiety with my foggy philosopy and transcendentalism, my thirst for something new, and my lack of purpose. But thanks to father, and Di, and yourself, I can see a rift in the clouds." (276)

"Editors' Table." Godey's Lady's Book Vol. 42 June 1851: 391-392.

Godey's was the woman's magazine of the period.

"A letter from a very earnest searcher after truth, asking a definition of that much-used-and-little-understood-word, `transcendentalism,' reminds us of the remark in on of the English periodicals, viz., that Mrs. Child had given the most intelligible and satisfactory definition the review had ever seen. We subjoin it:--

Transcendentalism -- All who know anything of the different schools of metaphysics are aware that the philosophy of John locke was based on the propositon that all knowledge is received into the soul through the medium of the senses; and thence passes to be judged of an analyzed by the understanding.

The German school of metaphysics, with the celebrated Kant at its head, rejects this proposition as false; it denies that all knowledge is received through he senses, and maintains that the highest, and therefore most universal truths, are revealed within the soul, to a faculty transcending the understanding. This faculty they call pure reason; it being peculiar to them to use that word in contradistinction to the understanding. To this pure reason, which some of their writers call `the God within,' they believe that all perceptions of the good, the true, and the beautiful are revealed, in its unconscious quietude; and that the province of the understanding, with its five handmaids, the senses, is confined merely to external things, such as facts, scientific laws."

Pictures from the Past

|

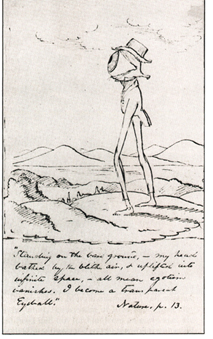

Caricature of Emerson's "transparent eyeball"

(From http://www.asd.k12.ak.us)

|

You guessed it: Thoreau's pencils

(from www.psymon.com/walden/ ad-pencils.html)

|

Page from Thoreau's journal on moving to Walden Pond (click to enlarge)

(From American Literary Autographs)

|

from

www.rev.net/~hmcmanus/ post/pm.htm

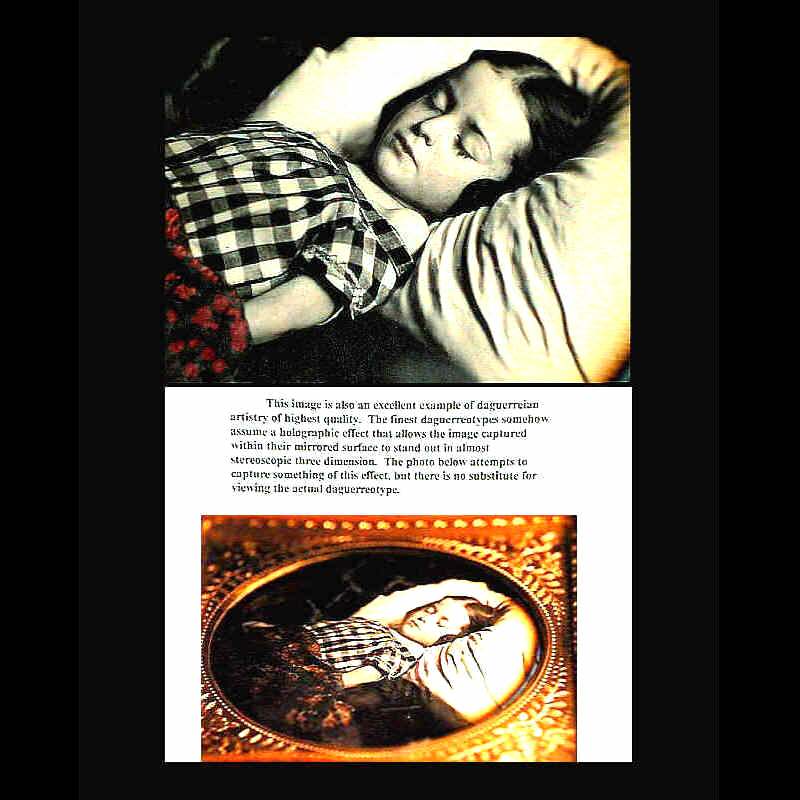

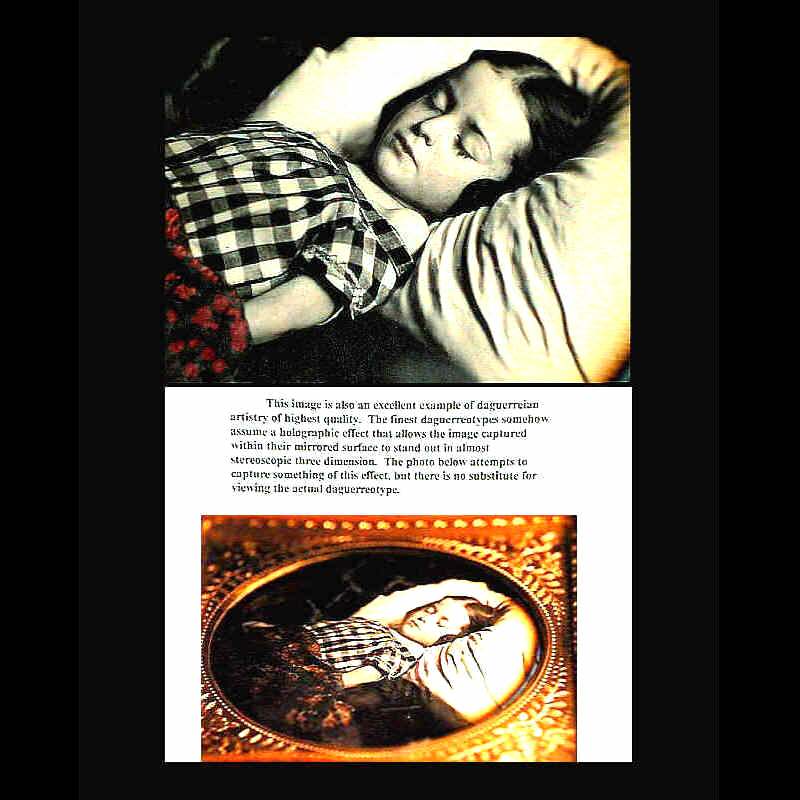

The image above is a

memento mori daguerreotype, a common way for people to remember

their love ones. Typically, the picture would be saved with a lock

of hair from the deceased. Note that Emerson writes in Nature

that "Even the corpse hath its own beauty" (1111)

Quotes from critics

Transcendentalism is a "somewhat late and localized manifestation of the European romantic movement. The triumph of feeling and intuition over reason, the exaltation of the individual over society, the impatience at any kind of restraint or bondage to custom, the new and thrilling delight in nature" (Horton and Edwards 116)

Sources: neo-Platonism, German idealist philosophy, and Eastern mystical writings : "From the first comes the belief in the importance of spirit over matter, and an ascending hierarchy of spiritual values rising to absolute Good, Truth, and Beauty. From the second, ...came the emphasis on intuition as opposed to intellect as a means of piercing to the real essence of things; while the last...contributed a kind of fuzzy mysticism that helped to bridge over the weak spots in a tenuous and unsystematic philosophy." (Horton and Edwards 116)

Emerson exhorted "young men to

slough off their deadening enslavement to the past, to follow the God

within, and to live every moment of life with a strenuousness that

rivaled that of the Puritan fathers. At the same time he insisted on

the oral nature of the universe, and pointed to nature as the great

object lesson proving God's presence everywhere in his creation. It

would not be far wrong to say that T. was Calvinism modified by the

assumption of the innate goodness of man." (Horton and Edwards 117)

"In addition to the neo-Platonism and the

Orientalism...we can detect the 'inner light' of the Quakers, the belief in the

divine nature of man as held by the Unitarians, and more than a touch of the

antinomianism of Anne Hutchinson." (Horton and Edwards)

Emerson "conceived on

an all-pervading unitary spiritual power from which all things emanate, and from

which man derives the divine spark of his inner being. Since the Oversoul is by

definition good, it follows that the universe is necessarily moral. Nature is

the new Bible wherein man may see a thousand times in a day fresh evidences of

the harmony and rightness of the world..." (Horton and Edwards 121)

Home Page | Lesson Plans | Supplemental Readings | Links

| Contact Dr. Bordelon

Last Revised October 2005

David Bordelon