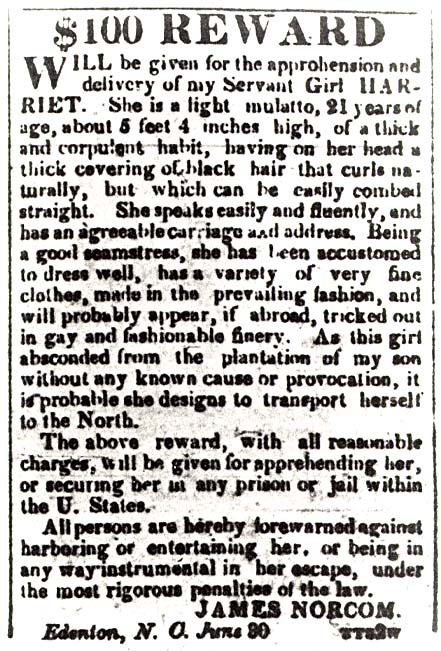

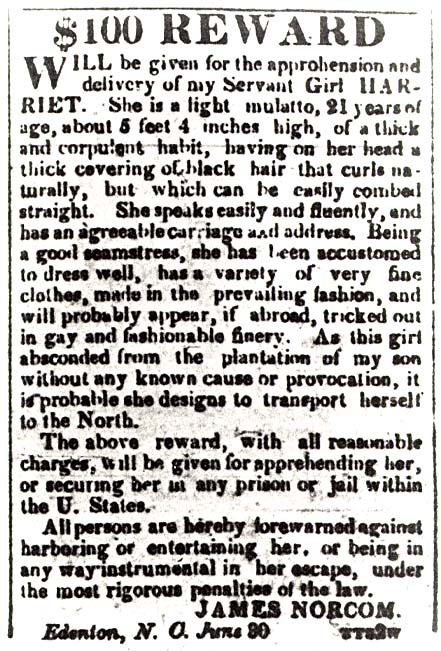

Classified ad by Jacobs "owner" with a reward for her return. Published in the American Beacon, July 4th 1835. Love the irony of the date.

|

Lesson Plan/Teaching Notes

How does this relate to Franklin’s Autobiography?

Terms/People to know

Domestic Fiction: This genre of novels and stories celebrate the Cult of True Womanhood, a belief, common in the nineteenth-century, that middle and upper-class white women (and those who aspired to such class and color) were "Angels of the Hearth," moral and religious exemplars who offered, in their homes/shrines, a respite from the vagaries of the cold, cruel world. This cult entails submission to authority (typically, though not always male), piety, purity, and attention and skill in domestic affairs (creating a comfortable home).

The critic Nina Baym (who edited our textbook with those erstwhile companions et al.) offers a succinct plot of a typical Domestic novel: "In essence, it is the story of a young girl who is deprived of the supports she had rightly or wrongly depended on to sustain her throughout life and is faced with the necessity of winning her own way in the world. This young girl is fittingly called a heroine because her role is precisely analogous to the unrecognized or undervalued youths of fairy tales who perform dazzling exploits and win a place for themselves i the land of happy endings. She also fits the pattern of comic hero, whose displacement indicates social corruption and whose triumph ensures the reconstruction of a beneficent social order. In Jungian perspective, her story exemplifies the difficult but successful negotiation of the undifferentiated child through the trials of adolescence into the individuation of sound adulthood. The happy marriages with which most -- though not all -- of this fiction concludes are symbols of successful accomplishment of the required task and resolutions of the basic problems raised in the story, which is in most primitive terms the story of the formation and assertion of a feminine ego" (11-12).

See Catherine Beecher Stowe and Harriet Beecher Stowe's American Women's Home for a period guidebook.

Baym, Nina. Woman's Fiction: A Guide to Novels by and about Women in America, 1820-1870 . Ithaca, New York: Cornell UP, 1978.

Middle Passage: " in the days of the African slave trade to the New World, the middle part of the slave's journey— i.e., the crossing of the Atlantic Ocean. From about 1518 to the mid-19th century, millions of African men, women, and children made the 21-to-90-day voyage aboard grossly overcrowded sailing ships manned by crews mostly from Great Britain, the Netherlands, Portugal, and France. Slaver captains anchored chiefly off the Guinea Coast for a month to a year to gather their cargoes of 150 to 600 persons. Then began a long period of continuous danger, with raids at port by hostile tribes, threats of slave mutiny, epidemics, attack by pirates or enemy ships, and bad weather. During the Middle Passage , male slaves were kept constantly shackled to each other or to the deck to prevent mutiny, of which 55 detailed accounts were recorded between 1699 and 1845. "

"Middle Passage." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 12 Dec. 2006 <http://www.search.eb.com/eb/article-9052545>.

Fugitive Slave Act: "in U.S. history, statutes passed by Congress in 1793 and 1850 (and repealed in 1864) that provided for the seizure and return of runaway slaves who escaped from one state into another or into a federal territory. The 1793 law enforced Article IV, Section 2, of the U.S. Constitution in authorizing any federal district judge or circuit court judge, or any state magistrate, to decide finally and without a jury trial the status of an alleged fugitive slave.

The measure met with strong opposition in the Northern states, some of which enacted personal-liberty laws to hamper the execution of the federal law; these laws provided that fugitives who appealed from an original decision against them were entitled to a jury trial. As early as 1810 individual dissatisfaction with the law of 1793 had taken the form of systematic assistance rendered to black slaves escaping from the South to New England or Canada—via the Underground Railroad.

The demand from the South for more effective legislation resulted in enactment of a second Fugitive Slave Act in 1850. Under this law fugitives could not testify on their own behalf, nor were they permitted a trial by jury. Heavy penalties were imposed upon federal marshals who refused to enforce the law or from whom a fugitive escaped; penalties were also imposed on individuals who helped slaves to escape. Finally, under the 1850 act, special commissioners were to have concurrent jurisdiction with the U.S. courts in enforcing the law. The severity of the 1850 measure led to abuses and defeated its purpose. The number of abolitionists increased, the operations of the Underground Railroad became more efficient, and new personal-liberty laws were enacted in many Northern states. These state laws were among the grievances officially referred to by South Carolina in December 1860 as justification for its secession from the Union. Attempts to carry into effect the law of 1850 aroused much bitterness and probably had as much to do with inciting sectional hostility as did the controversy over slavery in the territories.

For some time during the American Civil War, the Fugitive Slave Acts were considered to still hold in the case of blacks fleeing from masters in border states that were loyal to the Union government. It was not until June 28, 1864, that the acts were repealed."

" Fugitive Slave Acts ." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 12 Dec. 2006 <http://www.search.eb.com/eb/article-9035574>.

Discussion questions

from http://www.lehigh.edu/~ejg1/teach/logan2.html

Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

2. Jacobs' intended audience seems to be "women of the North." Discuss Jacobs' strategies for appealing to her audience. What does she leave in/out, and how does she treat different "incidents" with this audience in mind?

3. How does Jacobs seem to define slavery and freedom? What problems/conflicts seem to characterize each? How do her definitions compare with those of Douglass?

4. What are slavery's particular dangers to women? to the family? to the home?

5. Examine Chapter 10 as a variation on the seduction tale (The Coquette). How does Jacobs use and/or challenge this popular narrative form?

6. Using Chapter 16 as your base, what expectations exist for nineteenth-century women and how does slavery come into conflict with those expectations?

Discuss the significance of Linda's hiding place (Chapter 21). To what extent does it become a metaphor for the author's subversion of the master? To what extent does it bring the text's veracity into question?

Group Questions

Pictures from the Past

Classified ad by Jacobs "owner" with a reward for her return. Published in

the American Beacon, July 4th 1835. Love the irony of the date.

From www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/ part4/4h1541.html

Atlanta, 1864. From American Quarterly

Note the advertisements and what looks like a Union soldier reading next to the door.

Quotes from critic

Last Revised December 2006

David Bordelon