|

Course Documents Lesson Plans |

Dr. Bordelon's English II On Campus |

|||||||||

|

|

|

My Lai Massacre * For a compelling overview of My Lai, see the page below (note -- it's on a rather repellent site, but the material on the page I've linked is quite good). http://www.rotten.com/library/history/war-crimes/my-lai-massacre/ Another good My Lai site Long and detailed article on the massacre For a contemporary version of My Lai, see the following http://www.rotten.com/library/crime/prison/abu-ghraib/ |

Visual of a soldier's life: lots of "humping." |

|

Effects of naplam. See article on this famous picture |

Walking along a dike separating rice patties |

Connections between Vietnam and Iraq? See Ron Kovic's essay published on Truthdig. Note: it's a partisan view.

Vietnam

Glossary

In this novel you'll find several military acronyms, topical references,

etc., that may need a bit of explaining. Hence, a glossary.

Let's clarify three things, right off the bat.

Vietnam: Area/country in southeast Asia with an independent language, culture, and government. Partitioned into North and South Vietnam in 1954 in response to the western fear of communism, the two countries were rejoined in 1976 after the fall of the South Vietnamese government. During the war years, the country was bisected by the DMZ (Demilitarized Zone).

North Vietnam: The communist controlled area of Vietnam -- they wanted to unite the country under one rule. South Vietnam's and, because of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), our enemy.

South Vietnam: The non-communist, nominally democratic (but really autocratic) area of Vietnam. Our ally due to SEATO which stated that any member which comes under attack will enjoin all members in its defense. South Vietnam and America were members: North Vietnam was not.

|

Interactive Vietnam map |

||||

|

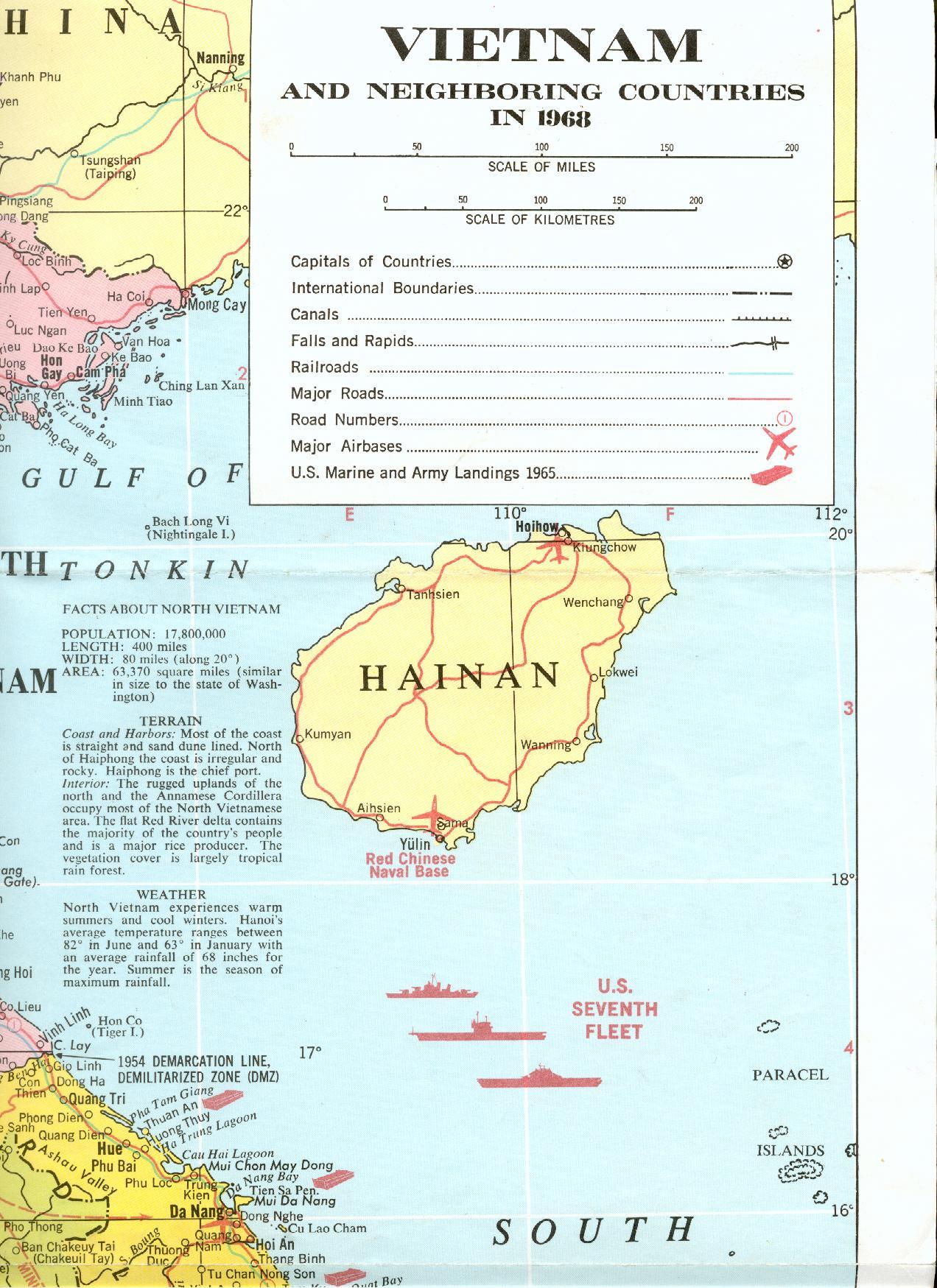

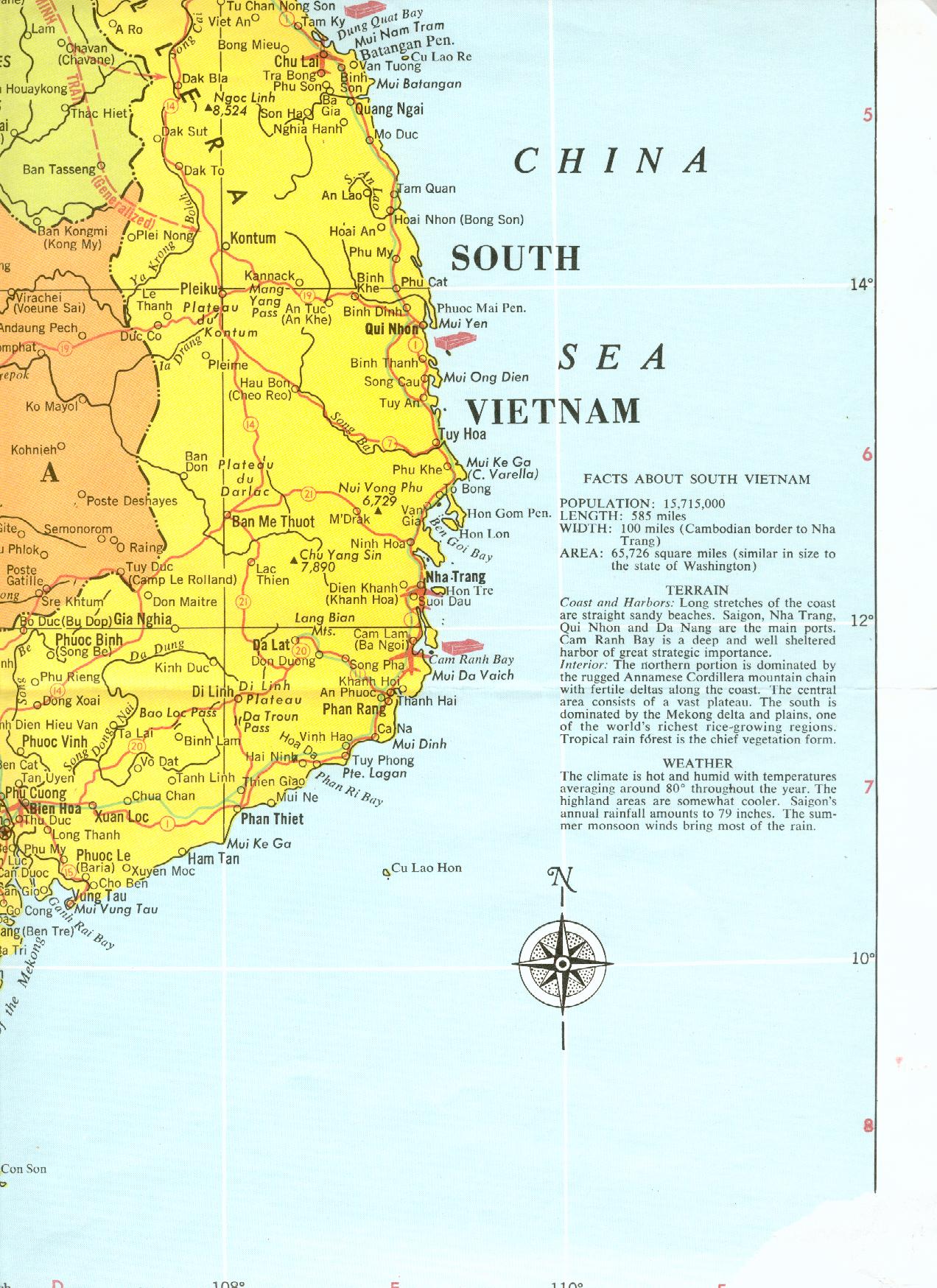

Period Maps (circa. 1968) click to view 1968 (period map) |

AK-47: Standard issue rifle used by North

Vietnamese. Cheap, reliable, deadly. Now a designer weapon for drug

dealers.

America: love it or leave it: phrase adopted by the great unthinking class as

a response to protests against the war. It stifles dissent by suggesting

that "you're either with merica', or you're with the

terrorists." Oops, wrong war -- but same idea.

ARVN Army of the Republic of Vietnam. Considered poor

fighters by US service men.

Bao Dai: The "playboy emperor." Last emperor

of Vietnam, courted and assisted by both communist and American regimes

because "the people" accepted him as a sovereign ruler. An

opportunist, and for that reason, a survivor.

Bouncing Betty: a type of land mine. After a soldier,

civilian, or water buffalo would step upon it, a little rocket/bomb would

shoot up that exploded at about waist height. Usually deployed by the

North Vietnamese.

Claymore: rectangular mine set off by remote control. It

would send a shower of lead in a triangular killing field. Usually

deployed by Americans. See picture below

Diem, Ngo Dinh: Autocratic ruler of South Vietnam from

1955-63. Corrupt, a Roman Catholic in a Buddhist country, he was propped

up by American officials because of his hard line stance against

communism. Assassinated by his own military in a 1963 coup.

domino theory: argument used by American political leaders

to support a war against communism. They believed that if one country

fell to communism, then others around it would fall as well (like a line of

dominoes). What they never seemed to address was why communism would

prove so attractive. I mean, it's not a virus or anything, it's merely a

political system.

Gook: US military slang for a Vietnamese person.

Gulf of Tonkin: located in North Vietnam (see map

above). Important because US military and intelligence reported that a

Navy destroyer, the USS Maddox, was attacked by North Vietnamese gunboats in

1964, which lead to a resolution to increase military presence and its role

in South Vietnam. It is now generally accepted that the attack did not

take place and some feel that the military and intelligence agencies

perpetuated a hoax to prompt deeper US involvement in the war.

Hawks and doves: shorthand to describe support for (hawks)

or opposition to (doves) the war. Prominent hawks from the era include

John F. Kennedy (though he was there before the term really was bandied

about), Barry Goldwater, Richard Nixon, and Henry Kissinger.

The main dove mentioned in the novel is Senator and Democratic Presidential

Nominee Eugene McCarthy.

Ho Chi Minh: The political and spiritual (in an agnostic

sense) leader of North Vietnam. In the 1950s, after reading the

Declaration of Independence, he approached American officials in France

(where he was educated) and asked them for his help in overthrowing the

French colonial powers. We refused due to treaty alliances and because of

cheap rubber (Vietnam's primary export) and Minh then turned to Russia and

China for support.

R&R: Rest and relaxation. A vacation from the

battlefield typically involving a trip (or trips) to a brothel, drinking,

and, if such was your preference, drugs. Sleep and good food as well. In

other words, creature comforts for 19 year old males.

klicks: slang for kilometers

Eugene McCarthy: presidential candidate in 1968 elections

who was against the war. To support him meant you too were against the

war.

M-16: Standard issue rifle used by the US and South

Vietnamese. It was expensive, semi-reliable, and deadly. Because of

its toy-like look, it has not become a designer weapon for drug dealers.

Three for one: 1) M-16 rifle; 2) Flack Jacket; 3) "hootch" or grass house, typical of Vietnamese civilian villages. Very flammable -- which helped make napalm (see below) such a useful (?) military tool.

from http://s88.photobucket.com/albums/k188

mortar: tube like cannon, easily hidden, transported, and

operated. A favorite of the Viet Cong.

napalm: bombs filled with jelled gasoline which ignites on

contact with the air. Usually dropped from jets which resulted in a

streak of fire (momentum of bomb would spread flame).

tracer rounds: bullets treated with a chemical to make them

flammable on contact. If fired at night would leave a streak of light --

handy for aiming, though it also made a great target.

Sterno: metal cans of jelled petroleum. Pop the top,

instant stove.

Tran Hung Dao: Vietnamese general who repelled Mongol

invasions in the 13C. (roughly equivalent to George Washington in

America -- i.e. military founding father).

Tot Dong: field where the Vietnamese defeated the Chinese in

1426, leading to their independence (think Bunker Hill).

VC: short for Viet Cong, the communist guerilla fighters who

lived in South Vietnam.

Walked point: walking at the head of line of soldiers in a

patrol. Dangerous because you would be the first person to encounter a

landmine, sniper, or ambush.

Willie Peter: Short for White Phosphorous, a incendiary

explosive material.

Questions to Mull Over As You Read

"Things They Carried"

- Consider the following sentences "It was't cruelty, just stage presence. They were actors" (20). Why? Why characterize the soldiers as "actors"? And what effect does this have on their actions -- and our understanding of them?

- Why the accumulation of specific weight and specific detail in the lists of the things they carry? What effect does it have on the reader? And how do they contrast with the other paragraphs in the story?

- What is LTV. Cross crying about (17)? What is this story really "about"?

- Why is this the first story/chapter in the novel? How does it connect to the other stories?

"Spin"

- How does this story function as a foreshadowing for the rest of the novel? Pick out pages/details and explain.

"On the Rainy River"

- Why does the narrator work in a pig slaughter house? Does it foreshadow his experiences in Vietnam in some way? See, especially, page 42.

- Why is Tim so upset with the people that support the war?

- What is "courage" to the narrator? Given the story, do you agree or disagree with him?

- What is Elroy Berdhal's function in the story? Why not just have O'Brien standing on a windswept prominence, debating whether he should go to Canada or not? What does Berdhal represent?

General questions

- Consider the relevance of the following quote to the entire story: "Absolute occurrence is irrelevant. A thing may happen and be a total lie, another thing may not happen and be truer than the truth" (83). How does this relate to 1) the story/novel itself; 2) the nature of story telling in general?

- Which "True" is he talking about in the title of the story/chapter ("How to Tell a True War Story) -- the "happening-truth" or the "story-truth" ("Good Form" 179)? How can you tell -- or not tell? Does O'Brien feel this distinction is important? Why or why not?

- Trace the transformation of Mary Anne "Sweetheart:" she changes from ____ to _____. What could she symbolize? Why/how?

- What "Courage" is referred to in "Speaking of Courage"?

- How does the metaphor of the "shit field" resonate throughout the story. Why not, for example, a regular muddy field?

- How is imagination something positive in the book? (consider, for example, "Lives of the Dead," "Good Form"). How is it negative ("Thing They Carried," "Ghost Soldiers" -- other stories?)? What's the point?

- Why does Bowker taste the water at the end of "Speaking of Courage" (173)?

- What can the narrator O'Brien do that Bowker cannot? How can this ability save the narrator? (Consider "Notes")

- How does the narrator change? From what to what? (Take this in stages -- use particular chapters to trace this change) What stories show this? Where in those stories? Does your opinion of the narrator change?

- What's Linda doing in the novel? How does she or her story connect with other themes? If she and that chapter was not in the novel, how would it change? Another way of looking at this is why does "Lives of the Dead" conclude the novel?

- In an interview, O'Brien stated "If there is a theme to the whole book it has to do with the fact that stories can save our lives" (qtd. in Coffey 202). So, where's the theme? Point to at least three quotes that prove this.

Group questions #1

- What is Elroy Berdhal's function in the story? Why not just have O'Brien standing on a windswept prominence, debating whether he should go to Canada or not? What does Berdhal represent?

- Think about the following story connections: "Things They Carried" -- "Love" / "Speaking of Courage" -- "Notes." What is O'Brien attempting to construct/show with these stories pairs? It may help to connect these story pairs to "Good Form." Why does O'Brien include this ("Good Form" chapter? Why doesn't he place this chapter earlier?

- In an interview, O'Brien writes that "If there is a theme to the whole book it has to do with the fact that stories can save our lives" (qtd. in Publishers 202). How does the novel show this? Trace out this theme in the novel by showing that, indeed, the novel does argue that "stories can save our lives."

- Though ostensibly a war novel, the stories touch on many other issues as well. What, for instance, does the novel suggest about ____, _____, love, courage, how people cope?

Group questions #2

- Consider the relevance of the following quote to the entire story: "Absolute occurrence is irrelevant. A thing may happen and be a total lie, another thing may not happen and be truer than the truth" (83). How does this relate to 1) the story itself; 2) the nature of story telling in general?

- Much of the novel deals with questions of truth: write an essay that first states O'Brien's definition of truth ("For O'Brien truth is _______.") and then explains how the novels illustrates this definition.

- How does one of the questions O'Brien raises in the novel -- the slipperiness of truth, the ease with which people can be fooled, the apathy and willful ignorance of much American society, etc. -- manifest itself in 21st century America? Another way of answering this questions is to ask yourself "How is this novel still relevant?"

- Using the definition of metafiction which follows, explain how the novel can be interpreted as a work of metafiction:

Metafiction is a term given to fictional writing which self-consciously and systematically draws attention to its status as an artefact in order to pose questions about the relationship between fiction and reality. In providing a critique of their own methods of construction, such writings not only examine the fundamental structures of narrative fiction, they also explore the possible fictionality of the world outside the literary fictional text. (qtd. in Calloway)

- Using the description of postmodernism below, explain how the novel can be interpreted as a postmodern novel.

"Distinctive features of this school [postmodernism] include switching between orders of reality and fantasy (see magic realism), resort to metafiction, and the playful undermining of supposedly objective kinds of knowledge such as biography and history."

"postmodernism." The Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature. Eds. Margaret Drabble and Jenny Stringer. Oxford University Press, 2007. Oxford Reference Online. Web. 19 January 2012.

Works Cited

Kaplan, Steven. Understanding Tim O'Brien. Columbia, South Carolina: U of South Carolina, 1995.

Rudd, Mark. "We, the Young People." Ordinary Americans: U.S. History Through the Eyes of

Everyday People. Ed. Linda R. Monk. Alexandria, VA: Close Up Publishing, 1994.

248-49.

Sintoni, Joseph. "Our Country, Right or Wrong." Ordinary Americans: U.S. History Through the

Eyes of Everyday People. Ed. Linda R. Monk. Alexandria, VA: Close Up Publishing,

1994. 252.

- The Undying Certainty of the Narrator in Tim O'Brien's The Things They Carried. Steven Kaplan. Critique 35.1 (Fall 1993): p43-52. NOTE: if the link is not working on your computer, try lowering the privacy/security settings on your browser. If that does not work, click on the "Library Links" from the course menu on the left, go to "Literature Resource Center" and get this article (hint: search by subject "The Things They Carried" or author "Kaplan, Steven.")

- Salvation,

Storytelling, and Pilgrimage in Tim O'Brien's The Things They

Carried. Alex Vernon. Mosaic 36.4 (Dec. 2003): p171-188. NOTE:

if the link is not working on your computer, try lowering the

privacy/security settings on your browser. If that does not work, click

on the "Library Links" from the course menu on the left, go to

"Literature Resource Center" and get this article (hint:

search by subject "The Things They Carried" or author

"Vernon, Alex.")

- Making Things Present: Tim O'Brien's

Autobiographical Metafiction. Silbergleid, Robin.

Contemporary Literature, Spring2009, Vol. 50 Issue 1, p129-155, 27p.

(Article) CLICK ON PDF TO READ THE ARTICLE. NOTE: if the link is not

working on your computer, try lowering the privacy/security settings on

your browser. If that does not work, click on the "Library

Links" from the course menu on the left, go to "Literature

Reference Center" and get this article (hint: search by subject

"The Things They Carried" or author "Silbergleid,

Robin.")

PDF Full Text (1.5MB)

- `How to tell a true war story':

Metafiction in The Things They Carried. Calloway, Catherine.

Critique, Summer95, Vol. 36 Issue 4, p249, 9p. (Literary Criticism)

NOTE: if the link is not working on your computer, try lowering the

privacy/security settings on your browser. If that does not work, click

on the "Library Links" from the course menu on the left, go to

"Literature Reference Center" and get this article (hint:

search by subject "The Things They Carried" or author

"Calloway, Catherine.")

HTML Full Text PDF Full Text (283KB)

- Conversation with Tim O'Brien. Tim O'Brien and Tobey C. Herzog. Writing Vietnam, Writing Life: Caputo, Heinemann, O'Brien, Butler. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2008. p88-133. Rpt. in Short Story Criticism. Ed. Jelena O. Krstovic. Vol. 123. Detroit: Gale. Word Count: 21839. From Literature Resource Center. NOTE: if the link is not working on your computer, try lowering the privacy/security settings on your browser. If that does not work, click on the "Library Links" from the course menu on the left, go to "Literature Resource Center" and get this article (hint: search by subject "The Things They Carried" or author "Herzog, Tobey." You'll have to click on the "Biography" tab at the top of the page.)

- A Conversation with Tim O'Brien. Tim O'Brien and Patrick Hicks. Indiana Review 27.2 (Winter 2005): p85-95. NOTE: if the link is not working on your computer, try lowering the privacy/security settings on your browser. If that does not work, click on the "Library Links" from the course menu on the left, go to "Literature Resource Center" and get this article (hint: search by subject "The Things They Carried" or author "Hicks, Patrick." You'll have to click on the "Biography" tab at the top of the page.)

- An interview. Tim O'Brien and Martin Naparsteck. Contemporary Literature 32.1 (Spring 1991): p1-11. NOTE: if the link is not working on your computer, try lowering the privacy/security settings on your browser. If that does not work, click on the "Library Links" from the course menu on the left, go to "Literature Resource Center" and get this article (hint: search by subject "The Things They Carried" or author "Naparsteck, Martin." You'll have to click on the "Biography" tab at the top of the page.)

On a different note . . .

Below find links to essays which more generally address many of the same aspects of truth, fact, reality and perception as the novel.

- "The Most Curious Thing" by Errol Morris -- on torture at Abu Ghraib.

- Plato's Allegory of the Cave

- David Broyles "Why Men Love

War"

- From Ramparts magazine: "The Whole Thing Was a Lie"

- From the New York Times: "The Hollow Man"

Radio Essays

- Interesting audio essay on how facts can be slippery: Radiolab http://www.radiolab.org/2012/sep/24

- Audio essay on how easily people can be mislead by fiction . . . sound familiar? Radiolab http://www.radiolab.org/2008/mar/24

- Radio lab again: on time. One of the best discussions of Einstein’s theory of time. Strong connections to the last chapter.

- Studio 360: Daniela Schiller on Memory

© 2001 David Bordelon